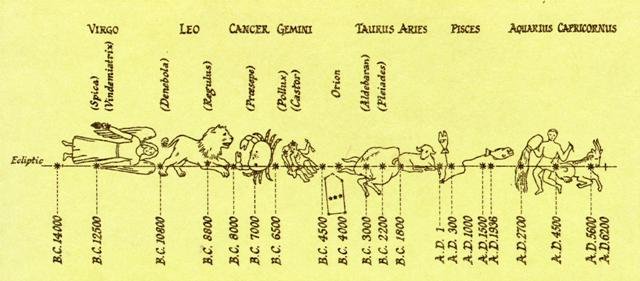

2. The right ascension ('longiturde') positions of the stars change over time and the total cycle of the precession has been estimated to be around 26000 years. This was well known since ancient times: ... The verdicts concerning the familiarity of ancient Near Eastern astronomers with the Precession depend, indeed, on arbitrary factors; namely, on the different scholarly opinions about the difficulty of the task. Ernst Dittrich, for instance, remarked that one should not expect much astronomical knowledge from Mesopotamia around 2000 B.C. 'Probably they knew only superficially the geometry of the motions of sun and moon. Thus, if we examine the simple, easily observable motions by means of which one could work out chronological determinants with very little mathematical knowledge, we find only the Precession.' There was also a learned Italian Church dignitary, Domenico Testa, who snatched at this curious argument to prove that the world had been created ex nihilo, as described in the first book of Moses, an event that supposedly happened around 4000 B.C. If the Egyptians had had a background of many millennia to reckon with, who, he asked, could have been unaware of the Precession? 'The very sweepers of their observatories would have known.' Hence time could not have begun before 4000, Q. E. D .

The 4 cardinal points of the Sun, the equinoxes and the solstices, were gradually changing their positions among the stars and therefore Wasat, for instance, rose with the Sun later and later in the calendar year. At the time when the rongorongo tablets were created Wasat would have risen with the Sun in July 8 instead of in ░July 4:

This 4-day difference can easily be calculated by using the formula 26000 / 365.25 = ca 71 years for moving the Sun 1 day earlier as measured against the stars, alternatively for moving the stars 1 day ahead in the Gregorian calendar. In order to distinguish the dates at the time of Gregory XIII from those ca 4 * 71 = 284 years later (approximately at the time of rongorongo) I found it necessary to add a little zero prefix, for instance: ░July 2. 188 was the day number for July 7, as counted from January 1 and 184 was the day number for ░July 3 (as counted from ░Janury 1). *111 was the number of days from March 21 (right ascension 0h) and *107 was the day number from ░March 21 (0h = 24h). *111 = 191 - 80 and *107 = 187 - 80. Day 80 in the Gregorian calendar was March 21 and right ascension 0h was there because the Pope had decided this should be the day of spring equinox. ... Ecclesiastically, the equinox is reckoned to be on 21 March (even though the equinox occurs, astronomically speaking, on 20 March in most years) ... ... When the Pope rearranged the day for spring equinox from number 84 ('March 25) to number 80 (║March 21) the earlier Julian structure was buried, was covered up (puo). At the same time the Pope deliberately avoided to correct the flow of Julian calendar days for what he may have regarded as 4 unneccesary leap days prior to the Council of Nicaea. Thus his balance sheet for days was in order. The day numbers counted from the equinox were increased with 4 and this was equal to allowing the 4 'unneccessary' leap days to remain in place. But he had moved spring equinox to a position which was 4 days too early compared to the ancient model ... These '4 unneccessary leap days' (prior to the Council of Nicaea) were equal in number to the precessional distance in time between the Pope and the time of rongorongo. The Gregorian calendar could therefore be easily understood by the Easter Islanders. The Pope had created a 'crooked calendar' but since his time the precession had fixed it. ... When the Pope Gregory XIII updated the Julian calendar he did not revise what had gone wrong before 325 AD (when the Council of Nicaea was held). Thus the stars were still 3-4 days 'out of tune' compared to the calendar ... the Gregorian 'canoe' was 'crooked'. His calendar was not in perfect alignment with the ancient star structure. Because he had avoided to adjust with the effects of the precession between the creation of the Julian calendar and the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. [The Julian equinox was in the 3rd month of the year and in its 25th day; 3-25.] Or as told in the language of myth: ... There is a couple residing in one place named Kui and Fakataka [meaning Creating a Cycle]. After the couple stay together for a while Fakataka is pregnant. So they go away because they wish to go to another place - they go. The canoe goes and goes, the wind roars, the sea churns, the canoe sinks. Kui expires while Fakataka swims. Fakataka swims and swims, reaching another land. She goes there and stays on the upraised reef in the freshwater pools on the reef, and there delivers her child, a boy child. She gives him the name Taetagaloa [meaning Not Tagaroa]. When the baby is born a golden plover flies over and alights upon the reef. (Kua fanau lā te pepe kae lele mai te tuli oi tū mai i te papa). And so the woman thus names various parts of the child beginning with the name 'the plover' (tuli): neck (tuliulu), elbow (tulilima), knee (tulivae). They go inland at the land. The child nursed and tended grows up, is able to go and play. Each day he now goes off a bit further away, moving some distance away from the house, and then returns to their house. So it goes on and the child is fully grown and goes to play far away from the place where they live. He goes over to where some work is being done by a father and son. Likāvaka is the name of the father - a canoe-builder, while his son is Kiukava .Taetagaloa goes right over there and steps forward to the stern of the canoe saying - his words are these: 'The canoe is crooked.' (kalo ki ama). Instantly Likāvaka is enraged at the words of the child. Likāvaka says: 'Who the hell are you to come and tell me that the canoe is crooked?' Taetagaloa replies: 'Come and stand over here and see that the canoe is crooked.' Likāvaka goes over and stands right at the place Taetagaloa told him to at the stern of the canoe. Looking forward, Taetagaloa is right, the canoe is crooked. He slices through all the lashings of the canoe to straighten the timbers. He realigns the timbers. First he must again position the supports, then place the timbers correctly in them, but Kuikava the son of Likāvaka goes over and stands upon one support. His father Likāvaka rushes right over and strikes his son Kuikava with his adze. Thus Kuikava dies. Taetagaloa goes over at once and brings the son of Likāvaka, Kuikava, back to life. Then he again aligns the supports correctly and helps Likāvaka in building the canoe. Working working it is finished ...

|