11. There were 10 Star Kings before the Deluge and the first one of them was Hamal (α Arietis): ... Strassmeier and Epping, in their Astronomishes aus Babylon, say that there its stars formed the third of the twenty-eight ecliptic constellations, - Arku-sha-rishu-ku, literally the Back of the Head of Ku, - which had been established along that great circle milleniums before our era; and Lenormant quotes, as an individual title from cuneiform inscriptions, Dil-kar, the Proclaimer of Dawn, that Jensen reads As-kar, and others Dil-gan, the Messenger of Light. George Smith inferred from the tablets that it might be the Star of the Flocks; while other Euphratean names have been Lu-lim, or Lu-nit, the Ram's Eye; and Si-mal or Si-mul, the Horn star, which came down even to late astrology as the Ram's Horn. It also was Anuv, and had its constellation's titles I-ku and I-ku-u, - by abbreviation Ku, - the Prince, or the Leading One, the Ram that led the heavenly flock, some of ķts titles at a different date being applied to Capella of Auriga. Brown associates it with Aloros, the first of the ten mythical kings of Akkad anterior to the Deluge, the duration of whose reigns proportionately coincided with the distances apart of the ten chief ecliptic stars beginning with Hamal, and he deduces from this kingly title the Assyrian Ailuv, and hence the Hebrew Ayil; the other stars corresponding to the other mythical kings being Alcyone, Aldebaran, Pollux, Regulus, Spica, Antares, Algenib, Deneb Algedi, and Scheat ... Also the beginning of Manuscript E has a king list:

The name of the first of these 10 (etahi te angahuru) kings (ariki motogi) in the land of Maori indicates he could have been Hamal:

Furthermore, a comparison with other king lists of this type suggests Hamal also was Adam, while Noah (before the deluge) could correspond to Hotu A Matua, the Full Moon (○) king. Beyond the Full Moon came the Waning Moon, ultimately leading to a complete disappearance beneath the waves at the New Moon (●), at high tide. ... When the new moon appeared women assembled and bewailed those who had died since the last one, uttering the following lament: 'Alas! O moon! Thou has returned to life, but our departed beloved ones have not. Thou has bathed in the waiora a Tane, and had thy life renewed, but there is no fount to restore life to our departed ones. Alas ...

Motogi is not matagi. Winds are drying things up, which is a force opposite to that of Vai-ora a Tane (the Living Waters of Tane).

... From the natives of South Island [of New Zealand] White [John] heard a quaint myth which concerns the calendar and its bearing on the sweet potato crop. Whare-patari, who is credited with introducing the year of twelve months into New Zealand, had a staff with twelve notches on it. He went on a visit to some people called Rua-roa (Long pit) who were famous round about for their extensive knowledge. They inquired of Whare how many months the year had according to his reckoning. He showed them the staff with its twelve notches, one for each month. They replied: 'We are in error since we have but ten months. Are we wrong in lifting our crop of kumara (sweet potato) in the eighth month?' Whare-patari answered: 'You are wrong. Leave them until the tenth month. Know you not that there are two odd feathers in a bird's tail? Likewise there are two odd months in the year.' The grateful tribe of Rua-roa adopted Whare's advice and found the sweet potato crop greatly improved as the result ... The Maori further accounted for the twelve months by calling attention to the fact that there are twelve feathers in the tail of the huia bird and twelve in the choker or bunch of white feathers which adorns the neck of the parson bird ...

Hamal was risong heliacally 4 days after Polaris and in Roman times this would have happened in the day before the Julian equinox ('March 25):

The sitting person in Gb7-27 is drinking water, but at the other side of Hamal his hand has developed into a sky (ragi) sign, i.e. in Roman times and at the Julian spring equinox ('March 25) the daytime (summer) sky was in front.

The sense of drinking water was made clear also by the front element in Gb7-26, viz. a hipu (calabash):

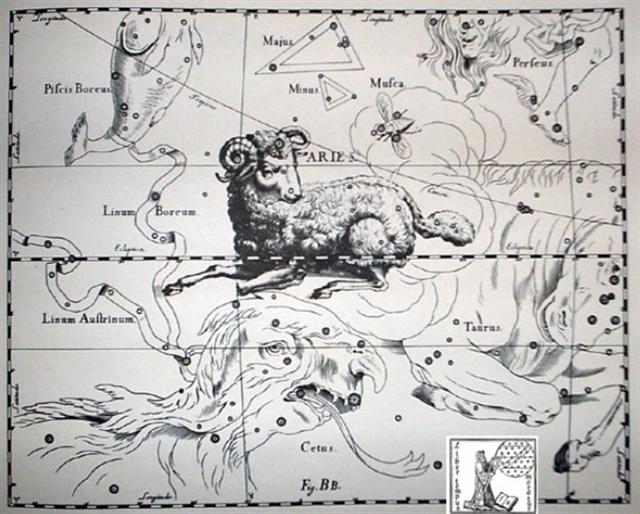

Hevelius has drawn Aries with Hamal at the forehead and with Sheratan and Mesarthim at the curved right horn. At the time of Hamal the stars γ (Mesarthim) and β (Sheratan) were still rising heliacally before the spring equinox - they were at the 'sweeping end curve' of winter:

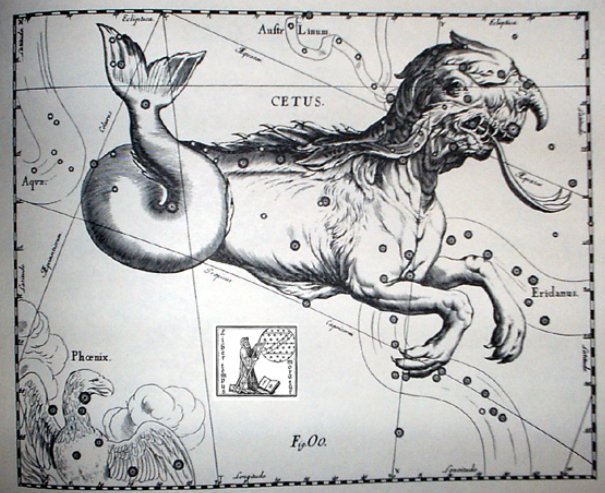

The Back of the Head of Ku could have referred to the back of the head of Cetus (the Sea Beast).

The return in spring of the 'fire' in the sky (the Sun) is hinted at by the Phoenix constellation drawn down in the left corner. ... A sidelight falls upon the notions connected with the stag by Horapollo's statement concerning the Egyptian writing of 'A long space of time: A Stag's horns grow out each year. A picture of them means a long space of time.' Chairemon (hieroglyph no. 15, quoted by Tzetzes) made it shorter: 'eniautos: elaphos'. Louis Keimer, stressing the absence of stags in Egypt, pointed to the Oryx (Capra Nubiana) as the appropriate 'ersatz', whose head was, indeed, used for writing the word rnp = year, eventually in 'the Lord of the Year', a well-known title of Ptah. Rare as this modus of writing the word seems to have been - the Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache (eds. Erman and Grapow), vol. 2, pp. 429-33, does not even mention this variant - it is worth considering (as in every subject dealt with by Keimer), the more so as Chairemon continues his list by offering as number 16: 'eniautos: phoinix', i.e., a different span of time, the much-discussed 'Phoenix-period' (ca. 500 years). There are numerous Egyptian words for 'the year', and the same goes for other ancient languages. Thus we propose to understand eniautos as the particular cycle beloning to the respective character under discussion: the mere word eniautos ('in itself', en heauto; Plato's Cratylus 410D) does not say more that just this. It seems unjustifiable to render the word as 'the year' as is done regularly nowadays, for the simple reason that there is no such thing as the year; to begin with, there is the tropical year and sidereal year, neither of them being of the same length as the Sothic year. Actually, the methods of Maya, Chinese, and Indian time reckoning should teach us to take much greater care of the words we use. The Indians, for instance, reckoned with five different sorts of 'year', among which one of 378 days, for which A. Weber did not have any explanation. That number of days, however, represents the synodical revolution of Saturn. Nothing is gained by the violence with which the Ancient Egyptian astronomical system is forced into the presupposed primitive frame. The eniautos of the Phoenix would be the said 500 (or 540) years; we do not know yet the stag's own timetable: his 'year' should be either 378 days or 30 years, but there are many more possible periods to be considered than we dream of - Timaios told us as much. For the time being the only important point is to become fully aware of the plurality of 'years', and to keep an eye open for more information about the particular 'year of the stag' (or the Oryx), as well as for other eniautio, especially those occurring in Greek myths which are, supposedly, so familiar to us, to mention only the assumed eight years of Apollo's indenture after having slain Python (Plutarch, De defectu oraculorum, ch. 21, 421C), or that 'one eternal year (aidion eniauton)', said to be '8 years (okto ete)', that Cadmus served Ares ...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||