108. In the C text we should now try to go back 180

glyphs from Altair in Cb4-20 (483 = 3 * 161) in order to

find the leading (first Greek lettered) star in Cancer,

viz. to MAY 16:

Which at the time of rongorongo corresponded

to day 136 + 64 = 200 (July 19). On Easter

Island the winter month of July was as dark

as January

north of the equator - a bad place (inoino).

|

Kino 1.

Bad; kikino, very bad,

cursed; kona kino, dangerous

place. 2. blemish (on body).

Kinoga, badness, evil,

wickedness; penis. Kinokino,

badly made, crude: ahu kinokino,

badly made ahu, with coarse,

ill-fitting stones. Vanaga.

1. Bad, wrong. T

Pau.: kiro, bad, miserable.

Mgv.: kino, to sin, to do

evil. Mq.: ino, bad,

abominable, indecent. Ta.: ino,

iino, bad, evil; kinoga

(kino 1) sin; Mgv.: kinoga,

sin, vice. 2. A skin eruption,

verruga, blotched skin, cracked feet

T. Churchill. |

|

MAY

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 (130) |

|

|

|

|

|

Ca11-10 (310 - 16) |

Ca11-11

(295) |

Ca11-12 |

Ca11-13 |

|

etoru inoino |

hakahagana hia to

rima - te inoino |

|

July 10 (191) |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

'June 14 (164) |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

"May 30 (150) |

31 |

1 |

2 |

|

MAY 11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 (136) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ca11-14 |

Ca11-15 |

Ca11-16 |

Ca11-17 |

Ca11-18 |

Ca11-19 |

|

tupu toona rakau i

te vai |

te moko |

te marama |

te kava |

ihe manu kara

etahi |

te mauga e hiku

hia |

|

July 14 |

15

POLLUX

(*116) |

16

AZMIDISKE (Ξ in ARGO NAVIS)

|

17

Φ Gemini (*118) |

18

DRUS (Χ in ARGO NAVIS) |

19 (200)

Ω CANCRI (*120) |

|

'June 17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

SOLSTICE |

22 (173) |

|

"June

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 (159) |

|

Hiku

Tail; caudal fin. Hikukio'e,

'rat's tail': a plant (Cyperus

vegetus). Vanaga.

...

In the deep night before the image

[of Lono] is first seen,

there is a Makahiki ceremony

called 'splashing-water' (hi'uwai). Kepelino

tells of sacred chiefs being carried

to the water where the people in

their finery are bathing; in the

excitement created by the beauty of

their attire, 'one person was

attracted to another, and the

result', says this convert to

Catholicism, 'was by no means good'

...

(Islands of History) |

|

|

|

|

Ca11-20 |

Ca11-21 |

Ca11-22 |

|

te inoino |

te hokohuki |

te moko |

|

|

|

|

|

Ca11-23 |

Ca11-24 |

Ca11-25 |

Ca11-26 (310) |

|

te inoino erua |

te hokohuki |

te moko |

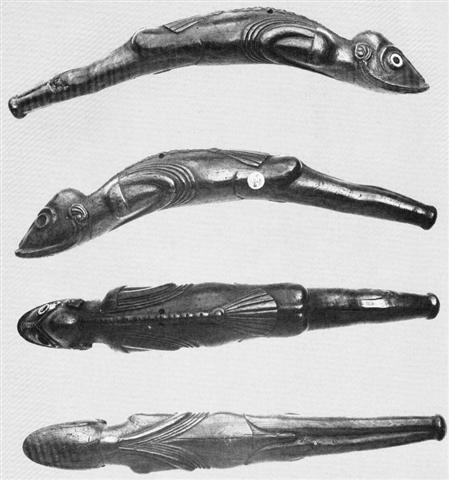

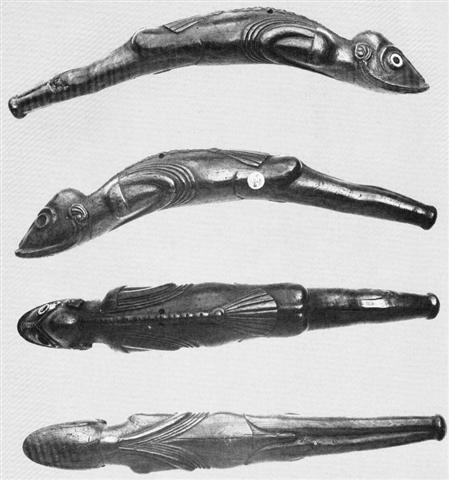

At a certain time they made feast and buried

Te Moko - a painted coral stone:

...

A

une certaine saison, on amassait des vivres,

on faisait fête On emmaillotait un corail,

pierre de défunt lezard, on l'enterrait,

tanu. Cette cérémonie était un point de

départ pour beacoup d'affaires, notamment de

vacances pour le chant des tablettes ou de

la priére, tanu i te tau moko o tana pure,

enterrer la pierre sépulcrale de lézard de

sa prière

...

The implication was probably

a descent down into the Underworld, a way to

continue the recycling from one generation

to the next:

... He continued travelling until he reached

the house of Uetonga, whose name all

men know: he was the tattoo expert of the

world below, and the origin and source of

all the tattoo designs in this world.

Uetonga

was at work tattooing the face of a chief.

This chief was lying on the ground with his

hands clenched and his toes twitching while

the father of Niwareka worked at his

face with a bone of many sharpened points,

and Mataora was greatly surprised to

see that blood was flowing from the cheeks

of that chief. Mataora had his own

moko, it was done here in the world

above, but it was painted on with ochre and

blue clay. Mataora had not seen such

moko as Uetonga was making,

and he said to him, 'You are doing that in

the wrong way, O old one. We do not do it

thus.'

'Quite so,' replied Uetonga, 'you do

not do it thus. But yours is the way that is

wrong. What you do above there is tuhi,

it is only fit for wood. You see,' he said,

putting forth his hand to Mataora's

cheek, 'it will rub off.' And Uetonga

smeared Mataora's make-up with his

fingers and spoiled its appearance. And all

the people sitting round them laughed, and

Uetonga with them

...

.. When

the man, Ulu, returned to his wife

from his visit to the temple at Puueo,

he said, 'I have heard the voice of the

noble Mo'o, and he has told me that

tonight, as soon as darkness draws over the

sea and the fires of the volcano goddess,

Pele, light the clouds over the crater

of Mount

Kilauea, the black cloth will cover my

head. And when the breath has gone from my

body and my spirit has departed to the

realms of the dead, you are to bury my head

carefully near our spring of running water.

Plant my heart and entrails near the door of

the house. My feet, legs, and arms, hide in

the same manner. Then lie down upon the

couch where the two of us have reposed so

often, listen carefully throughout the

night, and do not go forth before the sun

has reddened the morning sky. If, in the

silence of the night, you should hear noises

as of falling leaves and flowers, and

afterward as of heavy fruit dropping to the

ground, you will know that my prayer has

been granted: the life of our little boy

will be saved.' And having said that, Ulu

fell on his face and died.

His wife

sang a dirge of lament, but did precisely as

she was told, and in the morning she found

her house surrounded by a perfect thicket of

vegetation. 'Before the door,' we are told

in Thomas Thrum's rendition of the legend,

'on the very spot where she had buried her

husband's heart, there grew a stately tree

covered over with broad, green leaves

dripping with dew and shining in the early

sunlight, while on the grass lay the ripe,

round fruit, where it had fallen from the

branches above. And this tree she called

Ulu (breadfruit) in honor of her

husband. The

little spring was concealed by a succulent

growth of strange plants, bearing gigantic

leaves and pendant clusters of long yellow

fruit, which she named bananas. The

intervening space was filled with a

luxuriant growth of slender stems and

twining vines, of which she called the

former sugar-cane and the latter yams; while

all around the house were growing little

shrubs and esculent roots, to each one of

which she gave an appropriate name. Then

summoning her little boy, she bade him

gather the breadfruit and bananas, and,

reserving the largest and best for the gods,

roasted the remainder in the hot coals,

telling him that in the future this should

be his food. With the first mouthful, health

returned to the body of the child, and from

that time he grew in strength and stature

until he attained to the fullness of perfect

manhood.

He became a mighty warrior in those days,

and was known throughout all the island, so

that when he died, his name, Mokuola,

was given to the islet in the bay of Hilo

where his bones were buried; by which name

it is called even to the present time

...

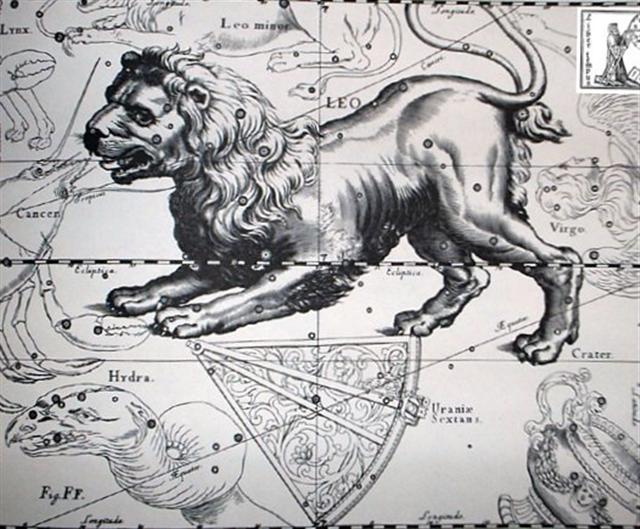

The Moko season could

perhaps have began in June 2 and ended at

the Nose of the Lion, 6 days after Acubens:

|

| Ca9-27 (255) |

| etoru gagata hakaariki kia raua |

| June 1 (152) |

|

|

|

| Ca10-1 (256) |

Ca10-2 |

Ca10-3 |

| Erua inoino |

kua hua te vai |

|

|

|

|

| Ca10-4 |

Ca10-5 (260) |

Ca10-6 (9 * 29) |

Ca10-7 |

| te kiore - te inoino |

kua oho te rima kua kai - ihe nuku hoi |

Tupu te toromiro |

kua noho te vai |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ca10-8 |

Ca10-9 (264) |

Ca10-10 |

Ca10-11 |

Ca10-12 |

| te moko |

te marama |

te kava |

manu rere |

te mauga tuu toga |

|

|

| Ca10-13 (268) |

Ca10-14 |

| kua tupu te mea - i te inoino |

ka tupu te toromiro - i te inoino |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ca10-15 |

Ca10-16 |

Ca10-17 (272) |

Ca10-18 |

Ca10-19 |

| rima heu ki te vai |

te moko oho mai |

te marama |

te kava |

manu rere |

|