485. The exceptional glyph number 384 = 2 * 192 = 6 + 378 (cycle of Saturn) - with a vacant space in its middle - seems to indicate where the Sun (once upon a time) had reached the thong leading from Alcor down to Spica:

... Proclus informs us that the fox star nibbles continuously at the thong of the yoke which holds together heaven and earth; German folklore adds that when the fox succeeds, the world will come to its end. This fox star is no other than Alcor, the small star g near zeta Ursae Majoris (in India Arundati, the common wife of the Seven Rishis, alpha-eta Ursae) ... The right ascension distance between Spica and Alcor was zero. The thong going down from Alcor could have been drawn at top right in the glyph, leading down to Spica south of the equator. The gap between the left and the right parts of the glyph might then represent the belt of the equator. The special place for Spica was evidently thought of as 'on the other side', for what could otherwise have motivated its location in the flag of Brazil:

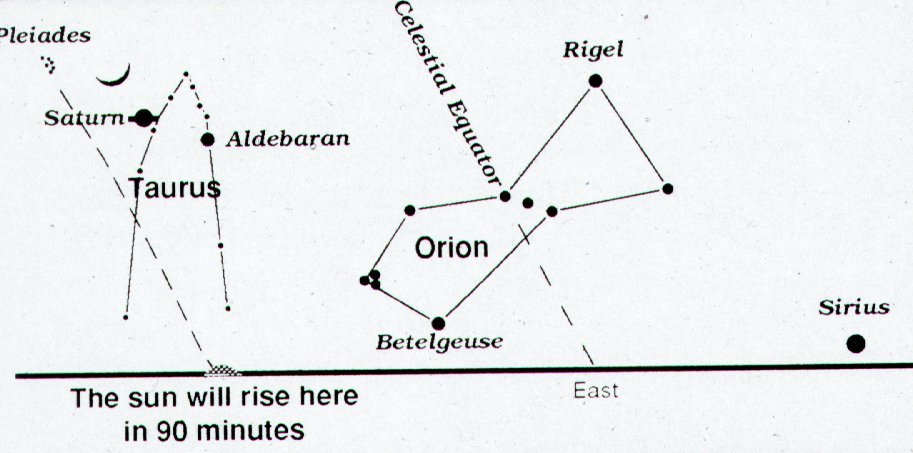

If this gap in the glyph was intended to represent the equator, then we should perceive south of the equator at right and north of the equator at left (drawn slightly higher up). On Easter Island the constellations would look upside down compared to what an observer north of the equator would see. And if we were standing on the equator, then the equator in the sky would be a vertical path with south to the right and north to the left:

Most of the homelands of the Polynesians were spread out in the equatorial belt. And what was seen above should correspond to what was below.

But at the poles the right ascension lines were coming together, as if lashed tightly together by a knot.

The right ascension days became shorter and shorter towards the poles one could say. On the other hand - as experience from visiting places in high latitudes had shown - the days of summer and the nights of winter became longer and longer. Eventually the pair of summer and winter turned into the pair day and night. North of the (northern) polar circle the Sun never went down in summer and never came up in winter. Time went slower and slower towards the poles. ... 'Tell us a story!' said the March Hare. 'Yes, please do!' pleaded Alice. 'And be quick about it', added the Hatter, 'or you'll be asleep again before it's done.' 'Once upon a time there were three little sisters', the Dormouse began in a great hurry: 'and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they lived at the bottom of a well — ' 'What did they live on?' said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking. 'They lived on treacle,' said the Dormouse, after thinking a minute or two. 'They couldn't have done that, you know', Alice gently remarked. 'They'd have been ill.' 'So they were', said the Dormouse; 'very ill'. Alice tried a little to fancy herself what such an extraordinary way of living would be like, but it puzzled her too much: so she went on: 'But why did they live at the bottom of a well?' 'Take some more tea [= t as in duration of time]', the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly. 'I've had nothing yet', Alice replied in an offended tone: 'so I can't take more [<]'. 'You mean you can't take less [>]', said the Hatter: 'it's very easy to take more than nothing'. 'Nobody asked your opinion', said Alice. 'Who's making personal remarks now?' the Hatter remarked triumphantly. Alice did not quite know what to say to this: so she helped herself to some tea and bread-and-butter, and then turned to the Dormouse, and repeated her question. 'Why did they live at the bottom of a well?' The Dormouse again took a minute or two to think about it, and then said 'It was a treacle-well.' 'There's no such thing!' Alice was beginning very angrily, but the Hatter and the March Hare went 'Sh! Sh!' and the Dormouse sulkily remarked 'If you ca'n't be civil, you'd better finish the story for yourself.' 'No, please go on!' Alice said very humbly. 'I wo'n't interrupt you again. I dare say there may be one.' 'One, indeed!' said the Dormouse indignantly. However, he consented to go on. 'And so these three little sisters - they were learning to draw, you know —' 'What did they draw?' said Alice, quite forgetting her promise. 'Treacle', said the Dormouse, without considering at all, this time. 'I wan't a clean cup', interrupted the Hatter: 'let's all move one place on.' He moved as he spoke, and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare moved into the Dormouse's place, and Alice rather unwillingly took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one who got any advantage from the change; and Alice was a good deal worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upsed the milk-jug into his plate ...

Thus, when Epimenides slept in a cave for 57 years it was as if he had been transported up to a polar region. ... The original story was by Diogenes Laertius, an Epicurean philosopher circa early half third century, in his book On the Lives, Opinions, and Sayings of Famous Philosophers. The story is in Chapter ten in his section on the Seven Sages, who were the precursors to the first philosophers. The sage was Epimenides. Apparently Epimenides went to sleep in a cave for fifty-seven years. But unfortunately, 'he became old in as many days as he had slept years'. Although according to the different sources that Diogenes relates, Epimenides lived to be one hundred and fifty-seven years, two hundred and ninety-nine years, or one hundred and fifty-four years. A similar story is told of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, Christian saints who fall asleep in a cave while avoiding Roman persecution, and awake more than a century later to find that Christianity has become the religion of the Empire ...

The corresponding place on side a of the C tablet carries 6 nights early in the Moon calendar - nights which no longer were tabu, no longer were sacred (Kokore, 'without'. Cfr Hawaiian: Ole-ku-tahi etc.): Kore. To lack, to be missing; without (something normally expected), -less; ana kore te úa, ina he vai when rain lacks there is no water: vî'e kenu kore, woman without a husband, i.e. widowed or abandoned by her husband. Vanaga. Not, without (koe); e kore, no, not; kore no, nothing, zero; kore noa, never, none; hakakore, to annul, to nullify, to annihilate, to abrogate, to acquit, to atone, to expiate, to suppress, a grudge. T Pau.: kore, not, without. Mgv.: kore, nothing, not, without, deprived of; akakore, to destroy, to annihilate. Mq.: kore, koé, óé, nothing, not, finished, done, dead, destroyed, annihilated, without. Ta.: ore, no, not, without. Korega, nothing, naught. Churchill.

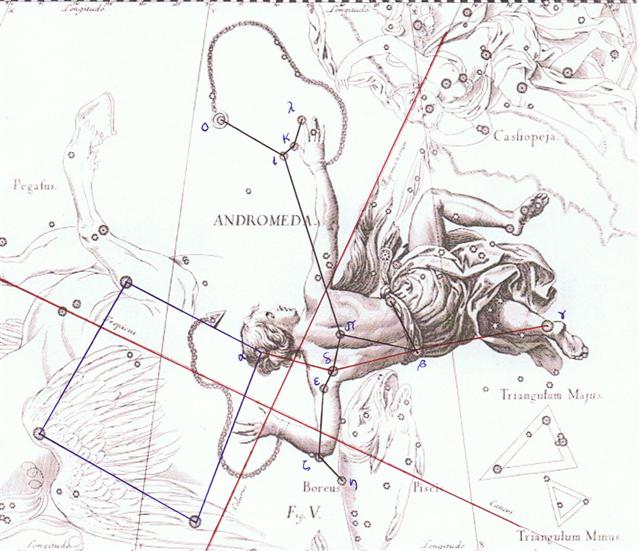

On side a of the tablet the glyphs seem here to tell about a season where light was arriving (open mouth in Ca6-28 → 168 = 6 * 28), whereas in contrast on the opposite side b we can read about 'ashes' (te kihikihi) and hanging victims (te rau hei), which ought to indicate the opposite - darkness arriving. Maybe turning the tablet around corresponded to crossing the equator. The stars were the same but evidenly the indicated opposite seasons. Close to the Full Moon people on Easter Island could in September (in principle, because the star was far away in the north) have observed the Chained Hand of Andromeda (Manus Catenata) - which was rising with the Sun in March 14 (→ 314 → π) - and they could therefore have concluded that their summer was not far ahead. In other words - the Moon calendar on side a of the C tablet ought to have represented the season when the Sun not yet had arrived and the Moon was still ruling 'in the night'. From a day somewhat later, when the Sun had arrived to Easter Island, it could imply we should read the glyphs (stars) according to the heliacal view, in which case te moko in Cb7-2 (about another year later) would be at the Snowball Nebula, which at the time of Bharani had risen with the Sun in right ascension day *314:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)