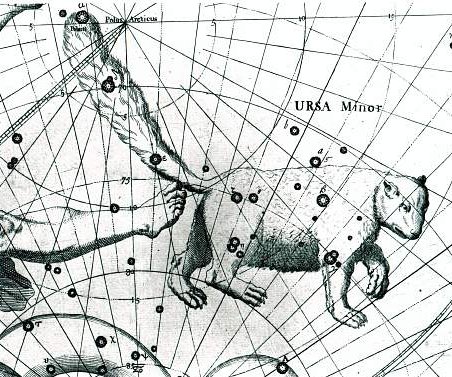

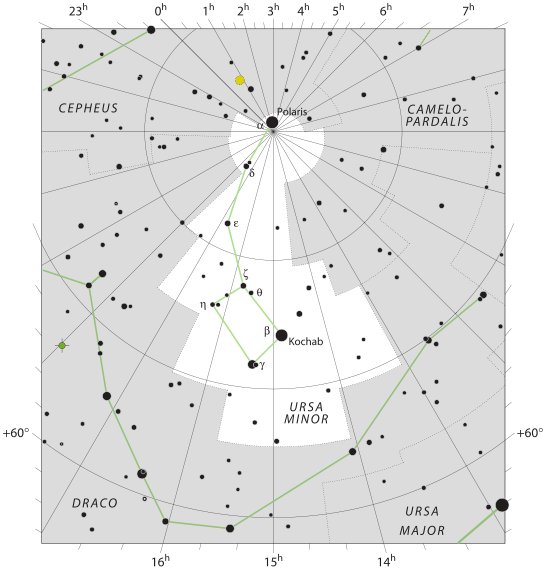

412. Polaris was at the tip of the tail of Little Bear and her beginning was at Kochab (Kakkab, the Star), which once upon a time also had been the position at the top.

... at the ancient time of Bharani the star at the North Pole was not Polaris but β Ursae Minoris - Kochab (as in Babylonian Kakkab = Star).

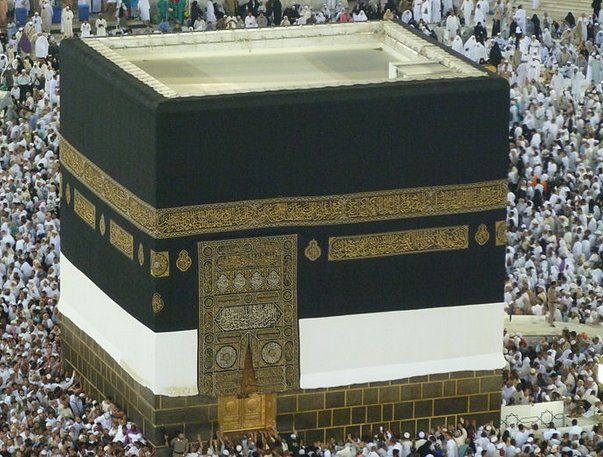

... Alrucaba, or Alruccaba, which probably should be Al Rukkabah, is first found in the Alfonsine Tables, although the edition of 1521 applied it only to the lucida. While this generally is supposed to be from the Arabic Al Rakabah, the Riders, Grotius asserted that it is from the Chaldee Ruku, a Vehicle, the Hebrew R'khūbh; and, if so, would seem to be equivalent to the Wain and from the Hebrew editor of Alfonso. Others have thought it from Rukbah, the Knee, as β always has marked the forearm of the Bear, and Alrucaba, in a varied orthography, was current for that star some centuries ago, as it is now for Polaris ... ... The creator of the C text has, as if to indicate contrast, put the current star at the north pole, Polaris, at the end of side a (i.e. 16 right ascension days/glyphs earlier in the text than Kochab, β Ursae Minoris), in the day preceding Sheratan (= The First Point of Aries in Roman times). When the Sun (in principle) reached Kochab then Polaris would (in principle) return to visibility - 16 days being the minimum period before a star would return in the early morning sky after having been too close to the Sun for observation ... ... The Arabs knew Polaris as Al Kiblah, 'because it is the star least distant from the pole', although then 5° away, and helped them, in any strange location distant from an established point of worship, to know the points of the compass and thus the direction to Mecca and its Kabah¹, towards which every good Muslim must turn his head in prayer. ¹ This ancient Square House, probably an early Sabaean temple, was built, tradition says, first in heaven; then for Adam on earth as a tabernacle of radiant clouds let down by the angels directly under its celestial site. This, disappearing at his death, was replaced by one of stone and clay by the patriarch Seth, that in its turn was swept away by the Deluge. Lastly it was erected by Abraham and Ishmael to contain the Black Stone, Al Hajar al Aswad, a ruby, or jacinth, brought from heaven by Gabriel and now blackened by the pilgrims' tears, or because so often kissed by sinners; but it is generally regarded by unbelievers as a meteorite. The Century Cyclopedia, however, describes it as an irregular oval about seven inches in diameter, composed of about a dozen smaller stones of various shapes and sizes. The Stone is set into the northeast corner of the wall, at a convenient height for kissing.

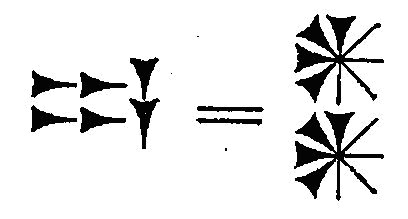

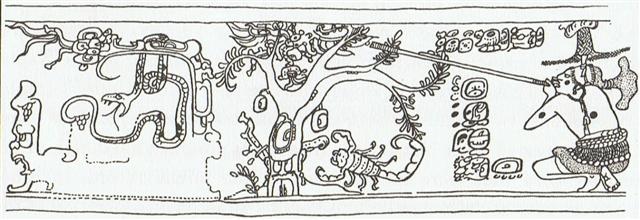

They also claled it Al Jadī, the Young He Goat, which subsequently degenerated to Juddah, as Niebuhr heard it a century ago, and known in Desert story as Giedi, the slayer of the dead man on the Bier of Ursa Major. Wetzstein says that in Damascus it is called Mismār, a Needle or Nail. As marking the north pole it bore the latter's title, Al Kutb al Shamāliyy, the Northern Axle, or Spindle, from Al Kutb, the Pin fixed in the under stone of a mill around which the upper stone turns; and this same thought later appeared in English poetry, as in Marlowe's History of Doctor Faustus, where he says of the stars that All jointly move upon one axletree // Whose terminine is term'd the world's wide pole. The Arabian astronomers knew it as Al Kaukab² al Shamāliyy, the Star of the North, ² Kaukab is the same as the Assyrian and Chaldean word Kakkab, the Hebrew Kōhābh; this last has also the fighting name of Bar Cochab, the Son of a Star, who was the leader of the second revolt of the Jews in 132-135, during the reign of Hadrian, his shekels bearing a star over a tetrastyle temple. The name was variosly written, but correctly as Bar Coziba, from his birthplace. an appellation perhaps given by their nomad ancestors to β [Kochab] as nearer the pole in their time ... ... The Young He Goat (Gredi), the slayer of the dead man imagined on the Bier - as defined by the 4 great star corners on the torso of Ursa Major (Itzam-Yeh) - could have been One-Ahaw:

Half a year measures around 365.25 / 2 = 182.625 (= 182½ + 1/8) days and when deciding where to put the stars at the opposite (nakshatra) side of the year this causes a problem. My method is to always add 183 days (implying a year which is documented as 366 days long but with 1 day leaped over - excepting every 4th year), but possibly the rongorongo writers used another method. ... The Heka triplet is where we otherwise would have expected to see a bright single star representing Orion's head (when looking from a location in the northern hemisphere) ... λ and the two stars phi furnish an easy refutation of the popular error as to the apparent magnitude of the moon's disc, Colas writing of this in the Celestial Handbook of 1892: In looking at this triangle nobody would think that the moon could be inserted in it; but as the distance from λ to φ¹ is 27', and the distance from φ¹ to φ² is 33', it is a positive fact; the moon's mean apparent diameter being 31' 7''. This illusion, prevalent in all ages, has attracted the attention of many great men; Ptolemy, Roger Bacon, Kepler, and others having treated of it. The lunar disc, seen by the naked eye of an uninstructed observer, appears, as it is frequently expressed 'about the size of a dinner-plate', but should be seen as only equal to a peppercorn ... 1' 7'' = 31.00238' / 60 = 0.5167º and 0.5167º / 360º * 365.25 = 0.52 days, i.e. the face of the Full Moon (Hotu) ought to be placed in a specific calendar day, but under no circumstances be stretched out to cover more than 2 days partially. Above I have chosen to add 182 in order to have Thuban and Hamal (respectively Polaris and Benetnash) close together, and the arrangement of the tresses at the back side of Pachamama suggests we should count not with 183 but with 182 right ascension days for one of the half-years:

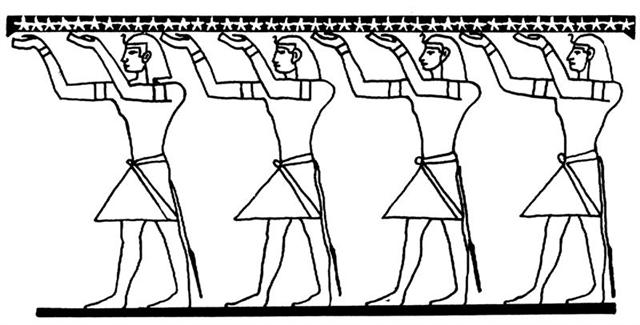

... In north Asia the common mode of reckoning is in half-year, which are not to be regarded as such but form each one separately the highest unit of time: our informants term them 'winter year' and 'summer year'. Among the Tunguses the former comprises 6½ months, the latter 5, but the year is said to have 13 months; in Kamchatka each contains six months, the winter year beginning in November, the summer year in May; the Gilyaks on the other hand give five months to summer and seven to winter. The Yeneseisk Ostiaks reckon and name only the seven winter months, and not the summer months. This mode of reckoning seems to be a peculiarity of the far north: the Icelanders reckoned in misseri, half-years, not in whole years, and the rune-staves divide the year into a summer and a winter half, beginning on April 14 and October 14 respectively. But in Germany too, when it was desired to denote the whole year, the combined phrase 'winter and summer' was employed, or else equivalent concrete expressions such as 'in bareness and in leaf', 'in straw and in grass' ... A winter 'year' measuring 6½ * 33 nights equals 214.5 and 182 / 6 = 26 days could be the length of a summer month. The Mayas had a year measuring 260 days: ... The Mayas called their 4 supporters of the sky Bacab: 'Among the multitude of gods worshipped by these people were four whom they called by the name Bacab. These were, they say, four brothers placed by God when he created the world at its four corners to sustain the heavens lest they fall.' (Diego De Landa according to Graham Hancock in his Fingerprints of the Gods.)

'In the ms. Ritual of the Bacabs, the cantul kuob [the suffix '-ob' indicates plural], cantul bacabob, the four gods, the four bacabs, occur constantly in the incantations, with the four colors, four directions, and their various names and offices.' (William Gates, An Outline Dictionary of Maya Glyphs.)

'... This connects up the present section with the beginning of the 'sacred tonalamatl', at the Spring equinox with the Mayas as with the Mexicans, and in the center of the 364-day year (52 days of which preceded and 52 followed the tonalamatl or tzolkin), ruled by its 91-day quarters by the Four Bacabs, whose quarternary repetition (in the 1820-day period) we have thus verified ...' (Gates, a.a.) ... 1820 = 20 * 91, i.e. the bacabs circulated 5 times in the 1820-day period, 5 * 364 = 1820, and 7 * 260 also happens to be 1820. They were ruling the 4 quarters of a 364-day long year, and in the center of this year there were 260 days, the sacred tonalamatl (tzolkin) calendar, which began at spring equinox:

... On February 9 the Chorti Ah K'in, 'diviners', begin the agricultural year. Both the 260-day cycle and the solar year are used in setting dates for religious and agricultural ceremonies, especially when those rituals fall at the same time in both calendars. The ceremony begins when the diviners go to a sacred spring where they choose five stones with the proper shape and color. These stones will mark the five positions of the sacred cosmogram created by the ritual. When the stones are brought back to the ceremonial house, two diviners start the ritual by placing the stones on a table in a careful pattern that reproduces the schematic of the universe. At the same time, helpers under the table replace last year's diagram with the new one. They believe that by placing the cosmic diagram under the base of God at the center of the world they demonstrate that God dominates the universe. The priests place the stones in a very particular order. First the stone that corresponds to the sun in the eastern, sunrise position of summer solstice is set down; then the stone corresponding to the western, sunset position of the same solstice. This is followed by stones representing the western, sunset position of the winter solstice, then its eastern, sunrise position. Together these four stones form a square. They sit at the four corners of the square just as we saw in the Creation story from the Classic period and in the Popol Vuh. Finally, the center stone is placed to form the ancient five-point sign modern researchers called the quincunx ...

|

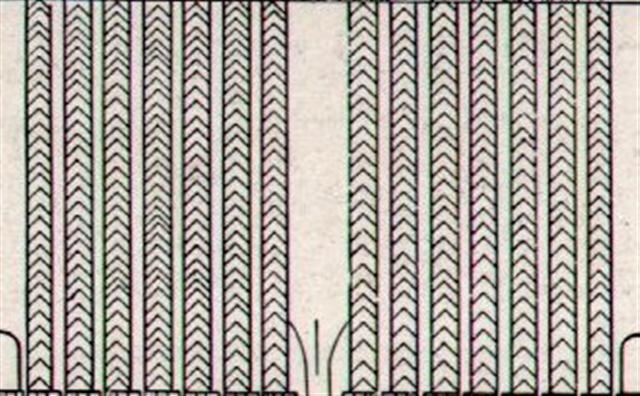

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||