|

TRANSLATIONS

If at noon a new day has been created, we cannot anyhow yet see him. We have to wait until the period of pregnancy is over and he will be born - i.e. until tomorrow morning. Still we have our old sun, now waving goodbye to us. He is on his path downwards. The sign in Ha6-9 (in the preceding period) with two thread-like appendages at left certainly must have something to do with the fact that at noon a new sun is created. We can compare:

In Pa5-55 the 'flame' (in the 7th period) is 'cut short', possibly meaning that a new sun will take over. If we regard the sun in Pa5-55 as the old sun of today, then that seems to be a reasonable explanation of why his 'flame' suddenly is 'blown out'. In Ha6-9, on the other hand, we see the new sun (of tomorrow) and instead of being 'blown out' he must have been 'ignited' a moment ago. Those bent 'threads' at left are certainly female in character (not being straight) and possibly the 'ignition' event should be sought in the earth oven (umu) of that old Nuahine kį umu a ragi kotekote.

At noon it certainly is at its 'hottest'. In old Bablyonia the word 'umu' meant 'lion', i.e. the solar animal as in e.g. the Sphinx:

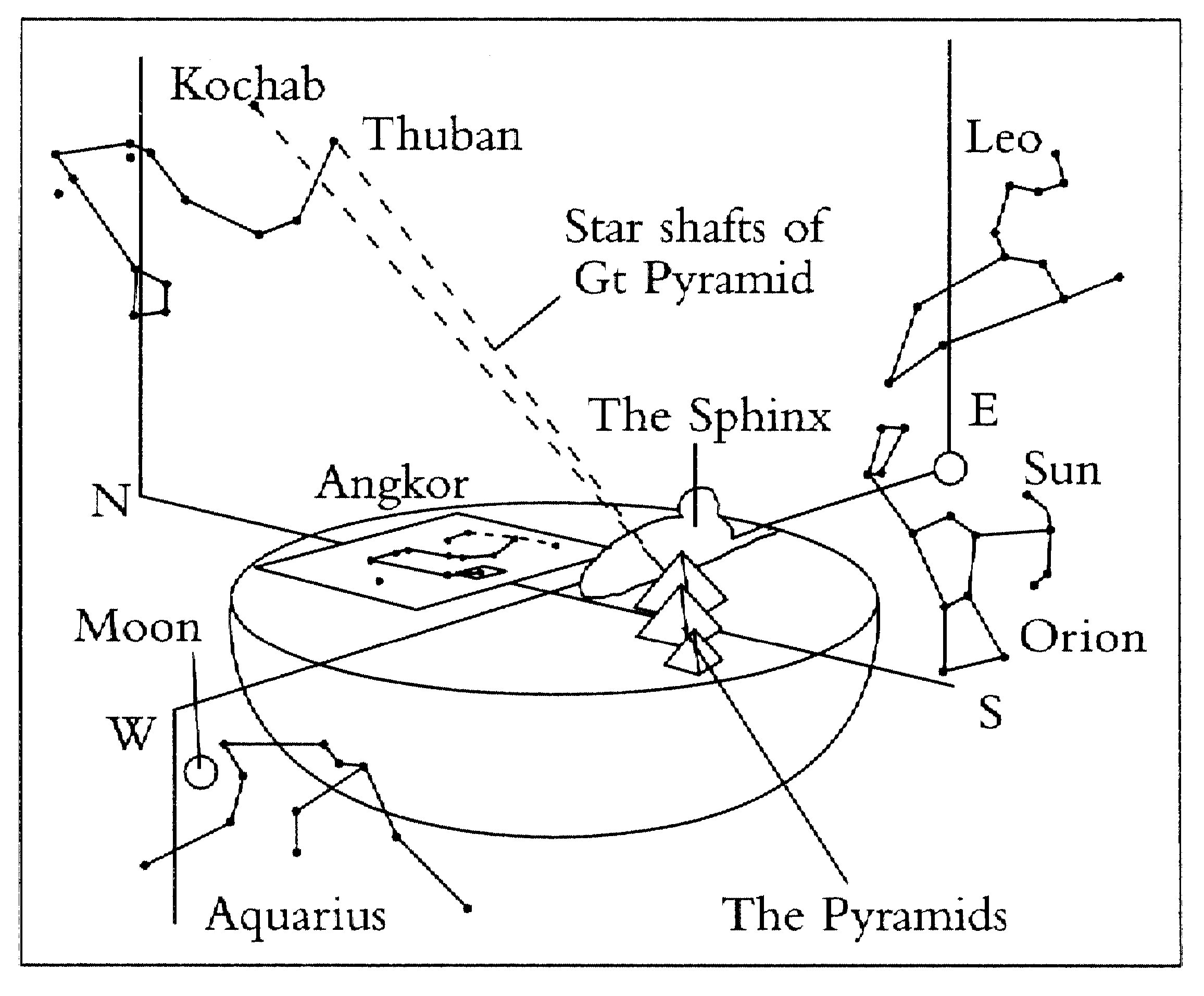

This picture (from Hancock 3) illustrates the spring equinox sky 10,500 BC with Leo preceding the sunrise. Due to the precession of the equinoxes in our days we have left Leo and are just on the verge to having Aquarius assuming that role, as half the precessional cycle is about 13,000 years. At the time of the Babylonians Leo ought to have been close to summer solstice (10,500 - 1/4 * 26,000 = 4,000 BC). So around 4,000 BC and at umu-time Leo should be the ruler. In Ha6-12 the hand points forward and the left two top flames of the sun also point in that direction. The same goes for the parallel glyphs in P, whereas in A the directions of the top flames are not so obvious (though probably 'in parallel'):

The fingers (except thumb) have the same direction as the left two top flames. Three fingers and two of the top flames point forward, the thumb and the right top flame point backwards. The arm is in Pa5-58 a converted flame, whereas in H and A the arm is a separate entity 'glued' to the bottom right flame. The bottom flames are symmetric, it seems, the left one pointing forward and the right one pointing backward. If we imagine the sun rotating counterclockwise, then the speed in that direction explains the direction of the two top flames at left. Or rather it explains the direction of the top middle flame (because the top left flame should be regarded as symmetric in relation both to the top right flame and the bottom left flame). The three fingers are presumably light rays, not straight as in hau tea but bent, i.e. a sign of the female. Old men change into women. The bent arm signifies that the path of the sun is bent. The elbow is presumably noon and the hand the end of the path - the soon to come sundown. In P the converted flame is the path of the sun, in A and H the path of the sun is a different entity. I think A and H is a better description, because the path of the sun is female, not male. The path of the sun is neither the sun himself nor the sun-rays but the reflection of the sun-rays on earth. In this glyph (Pa5-33)

we can see the sun-rays hitting the earth at the horizon. In the next (2nd) period (Pa5-37) not only the horizon but a rectangular piece of earth that we can see immediately in front of us is illumintated by the sun-rays:

The picture of two 'staffs' (two henua) is generated from the three sun-rays (which also illustrate the white generated by hau tea - perhaps by Atea beating tapa). Nowadays Atea is male, but henua still is female. The Chinese regarded that part of the earth which the sun illuminated as yang (male). The Polynesians do not agree, the receptor of something male must be female. In Ha6-13 we can see a modified double henua and logic tells us that maybe the wedges are the black impressions made by the mountains in the east (bottom) and in the west (top). Mountains in the west shut off the light earlier than if the horizon is free and mountains in the east delay the rising sun. The middle shorter vertical line perhaps represents the line due east - due west. Man-made mountains (pyramid etc) often are oriented so. On the other hand, the direction to the rising and setting sun varies over the year, and due east - due west occurs only at the equinoxes. Reflecting on this it might be more appropriate to show exactly this fact in the glyph, with the two outer vertical lines representing the lines between sunrise and sundown at the solstices. We thereby establish a glyph representing the 'square earth' (as bathed in the light of the sun). Like the tapa beater its squareness may be seen only on the ends. If we turn a double henua glyph to look at such an end, we will find that the end indeed is square, with corners at the equinoxes and solstices. It will look like this (Ca1-26):

But for making it clearer two suns have here been added (at the equinoxes). In a parallel glyph (Pa8-30) we can check the idea:

In the top middle we recognize 'noon' (or summer solstice, umu-time). The right leg (or rather left - from this person seen - because left means female) is converted into hua (which must mean winter solstice - or 'midnight' - as it is opposite to 'noon'). Moving counterclockwise (from us seen) the high in the air fist must mean 'morning' (spring equinox) and the low fist at the opposite side 'evening' (autumn equinox). Right (from us seen) elbow must then represent winter solstice (low) and the opposite elbow (high) summer solstice. The left leg is also bent and the knee must be a cardinal point. As the right leg is hua, the left knee should be autumn equinox (because in a counterclockwise motion that comes before winter solstice). The two legs in the normal tagata glyph:

show that the path of ligh is not 'circular' but extinguished between the feet. There we presumably change from one 'year' to the next (i.e. at 'winter solstice'). The leg opposite to the hua leg therefore should be the second half of the year and the knee 'autumn equinox'. The legs give us one representation of the 'year' and the arms another. In both representations we read counterclockwise. In Ha6-13 the 'vertical' (and no longer straight) line in tapa mea no longer is quite vertical:

Together we have 6 * 3 = 18 marks (= 36 / 2) and afternoon should be half the day. Counting glyphs we arrive at the following result:

There are 15 glyphs before noon and there seems to be 17 glyphs after noon, i.e. there are presumably altogether 32 glyphs in the day calendar of H. Counting glyphs in the night calendar of H we find 12 such glyphs, a nice sum. If we continue by counting 12 glyphs into the day calendar, we arrive at:

No. 13 is obviously a mature person and he does not belong to a.m. while no. 12 certainly not yet is ready for the afternoon. But all these 4 glyphs belong to the '5th' period. If we continue and count yet another 12 glyphs we arrive at:

which is the last period before sun dies. After that we need to count yet another 8 glyphs to reach the end of the day calendar and 12 + 8 = 20, a nice number. The number of glyphs in the night calendar (12) added to those glyphs in the day calendar which show juvenile signs (12) give us 24 glyphs, a nice number. Noon + afternoon glyphs (20 glyphs) added to 24 (night + a.m. glyphs) give us 44 glyphs. But then we have not considered some glyphs arriving after the day calendar which presumably belong to the total. Their number is not certain, because there are a few obliterated glyphs at the end of the day calendar and at the beginning of the sequence of these extra glyphs. I have guessed at 3 glyphs in the '10th' and last period of the day (where only part of one glyph remains). At the end of the sequence of extra glyphs (after the day calendar) there are 5 partially visible glyphs. Before them I would guess at 2 totally obliterated glyphs (judged by the parallel texts of A and P). 44 + 5 + 2(?) = 51 a not nice number. Therefore, there possibly are 3 totally obliterated glyphs, not 2, and that would result in 52 glyphs - the number of weeks in a year. The text in Tahua has the sequence of extra glyphs arriving immediately before the day calendar, an indication that the extra glyphs really belong to the two calendars. If we disregard the last two periods of the day, we find that those 20 glyphs for noon and p.m. may be divided into 13 + 7 glyphs. Similarly we could divide those 12 glyphs before noon into 7 + 5. The 'true' day therefore has 5 + 13 = 18 glyphs (½ * 36) and the 'transformation' periods have 7 + 7 = 14 glyphs (½ * 28). This number juggling may be a partial answer to why there is no 3rd period in H, there would simply be too many glyphs before noon to balance the 12 glyphs in the calendar of the night. Let us now return to Ha6-12 (and the parallel glyphs):

We have not yet explained the meaning of the thumb. Hand with a thumb like this marks the end of the day. It is time to indicate the end of the day already here in the '8th' period, because in next period sun 'dies'. We should disregard the 1st and last periods of the day, because they do not belong to the regular periods of the day. Both these extreme periods in a way belong to the night. The periods of 'birth' and 'death' (as well as noon) are also special, they correspond to cardinal points. 12 glyphs for the night, 12 for a.m. and 13 for noon and p.m. The last number is not nice. The thumb, therefore, marks the very last point of the 'living' sun. A similar type of sign we find in the 12th glyph of the day (Ha6-1):

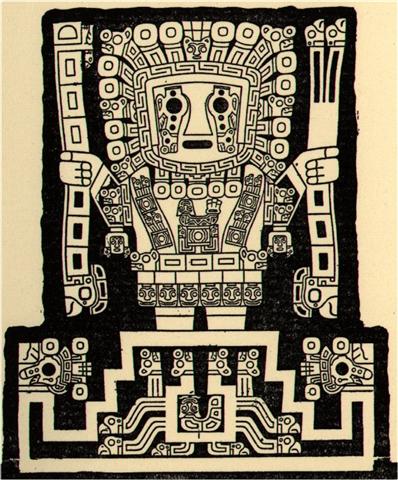

where the 'spike' in the right bottom flame also indicates a cardinal point (noon). The hand of the morning sun shows no thumb, because that sign is not used to mark a cardinal point. The thumbs marking the equinoxes (cardinal points) in the central sun figure at Tiahuanaco's Gateway of the Sun are used in a similar way:

|