|

TRANSLATIONS

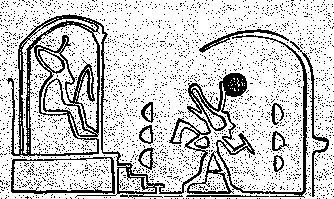

Sun with his strong rays is pushing the sky apart from earth and it is thereby steadily growing lighter. At Qa5-48 we hesitate, because henua (right) has at left a strange sign. Is it a snake? It does not look like a serpent. Rather at bottom left we see the sun in 'egg'-form ('skull') diving down into the earth, to reappear again at the top (i.e. later) as a newborn little henua. We must analyse this possibility. In Qa5-49 triple (vertical) sunrays define light beams, with a suggestion of earth being closer to the sky in the middle. Earth is convex (like an overturned boat) and the sky - it seems - has also that shape (though as in a mirror). In Qa5-50 we may use the idea of earth as an overturned boat to explain why tapa mea in H and Q has this general shape: It is the sunlit earth. The left, hollow, part is not lit up by the sun (no short marks illustrating sun rays), because that side is the underworld. At least it is not lit up during our day. In A we may by this explanation draw the conclusion that tapa mea there includes also the underworld:

As tapa mea means 'red cloth' we can guess that Qa5-49 (and similar glyphs) means 'white strip of cloth' (hau tea), because sun 'has' red colour and moon 'has' white colour; during the night (the time of the moon) white is the colour and when we have 'red' light from the sun those who live on the other side of the earth therefore must have 'white' light. In P, however, the artist has both hau tea and an oval (not hollow) tapa mea:

This should mean (given that the artist knew what he was doing) that hau tea in P (in this the 4th period) has some other (or additional) meaning to 'white strip of cloth'. We must investigate this thread of evidence. Qa5-47 has nearly the same appearance as Qa5-43 in the preceding period:

A close examination reveals that their hands are not exactly the same. Without trying to determine what the differences in detail might mean, we should at least acknowledge that the artist is right: The light pushing up the sky is not exactly the same in this period ('4th') as in the preceding one (2nd). The growing distance between the sky roof and the surface of the earth is illustrated as a 'hand of fire' feeding the young sun. Presumably the artist of Q (and also the artist of H) alludes to this young sun as a 'person'. If so, then there must be a succession. I therefore guess that the 'disc' of the bottom 'sun' is the prior generation, the remains of the sun of yesterday, the 'cranium' of whom is vitally important for the sun/son (hua) of today. The 'flames' of the old sun is pointing downwards, giving the impression that he has fallen on his face, signifying that he is 'dead'. The arm feeding the young sun appears from the middle of the 'stem' connecting old and new sun. They have a relation (the 'stem') and that not only results in a stream of nourishment but also implies support. The 'bud' at top is supported by a 'stem' appearing from the bulbous root. At noon this 'bud' will be turned into a 'flower'. Possibly we should also think magically here: The Babylonians 'saw' Marduk, the morning sun, as delivering not only light but also 'Wachtstum' = growth of vegetation. The sign of growth in this type of glyph could then be meant not only to describe growing light and the 'person' of the sun as growing, but also to act magically in order to enhance the growth in general in nature. Some flowers close up in the evening and need the sun to open again in the morning. And sun-flowers follow the sun with their 'faces' during the day. This I happened to learn yesterday evening from a TV-program about Vincent van Gogh. He painted sun-flowers and he also planned for a kind of sun cult with the half-Peruan Paul Gaugin involved. And Gaugin had lived in Polynesia. We should now continue the story of the 'renaissance' of the skull of Hotu A Matu'a: "Another year passed, and a man by the name of Ure Honu went to work in his banana plantation. He went and came to the last part, to the 'head' (i.e., the upper part of the banana plantation), to the end of the banana plantation. The sun was standing just right for Ure Honu to clean out the weeds from the banana plantation. On the first day he hoed the weeds. That went on all day, and then evening came. Suddenly a rat came from the middle of the banana plantation. Ure Honu saw it and ran after it. But it disappeared and he could not catch it. On the second day of hoeing, the same thing happened with the rat. It ran away, and he could not catch it. On the third day, he reached the 'head' of the bananas and finished the work in the plantation. Again the rat ran away, and Ure Honu followed it. It ran and slipped into the hole of a stone. He poked after it, lifted up the stone, and saw that the skull was (in the hole) of the stone. (The rat was) a spirit of the skull (he kuhane o te puoko).

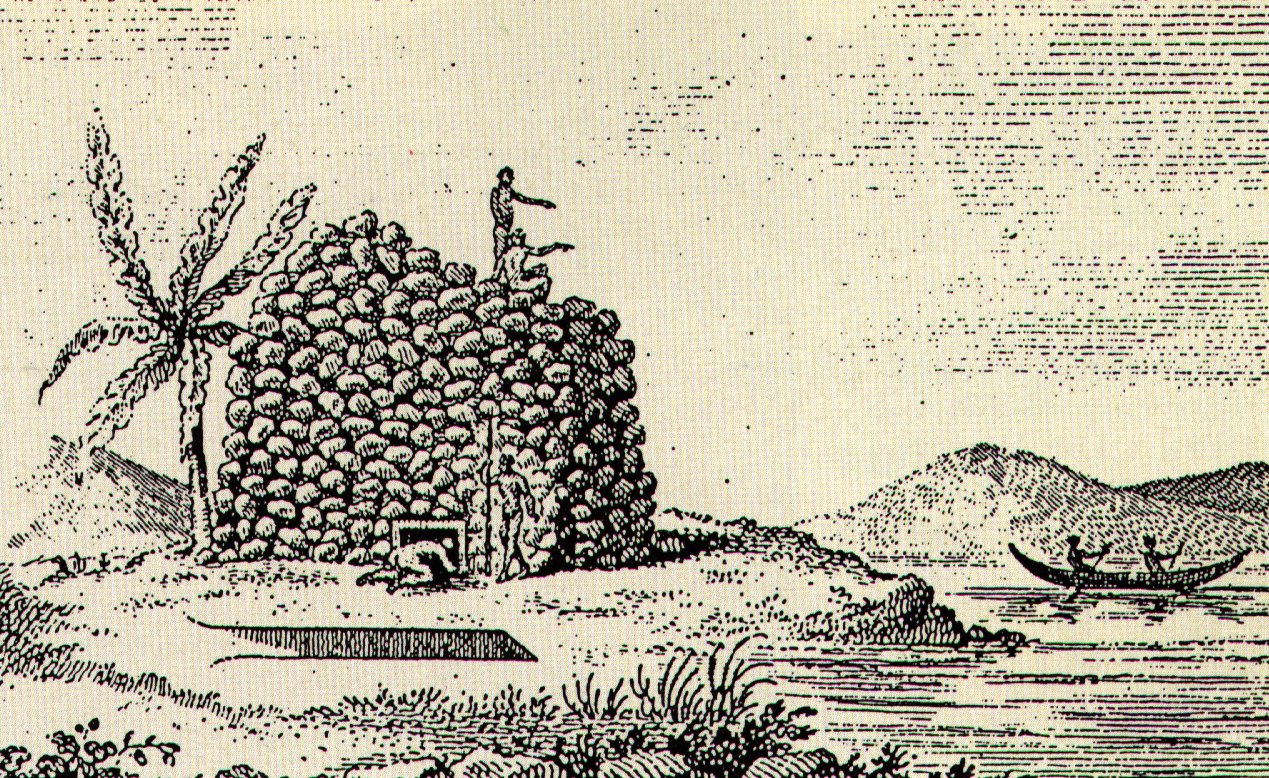

Ure Honu was amazed and said, 'How beautiful you are! In the head of the new bananas is a skull, painted with yellow root and with a strip of barkcloth around it.' Ure Honu stayed for a while, (then) he went away and covered the roof of his house in Vai Matā. It was a new house. He took the very large skull, which he had found at the head of the banana plantation, and hung it up in the new house. He tied it up in the framework of the roof (hahanga) and left it hanging there." This part of the story contains several clues. That rat should be the Black Rat (Kiore Uri), i.e. the night 'incarnation' of Hotu A Matu'a, and indeed we find it clearly said: The rat is the kuhane of the skull. The strip of barkcloth (nua = mother) represents the female taking care of the night side. "The barkcloth which provides access for the god/chief and signifies his sovereignity is the preeminent feminine valuable (i yau) in Fiji. It is the highest product of woman's labor, and as such a principal good of ceremonial exchange (soolevu). The chief's accession is mediated by the object that saliently signifies women." (Islands of History) The new house presumably represents a new solar period. The roof of this house and the sky dome should be equivalents. The architect should be the same:

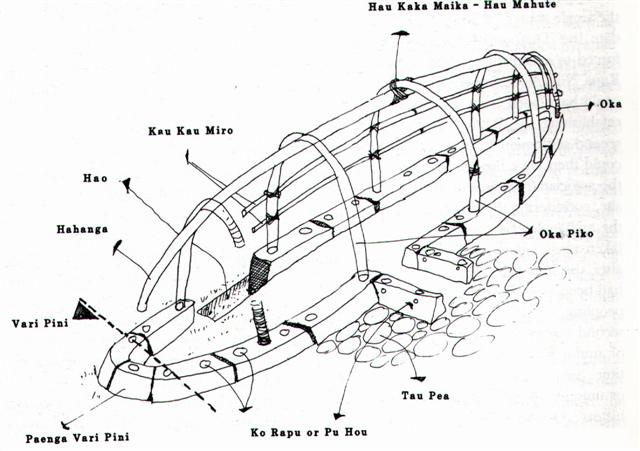

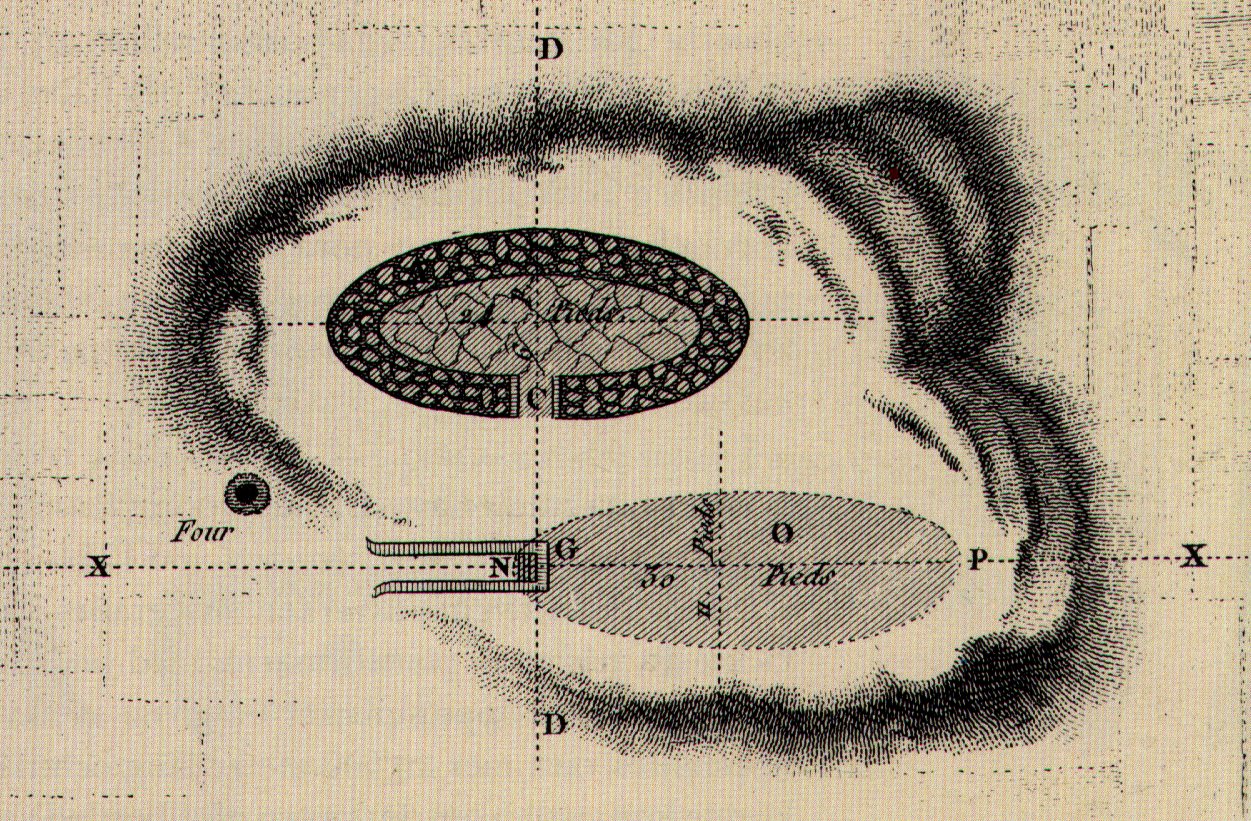

(picture from Van Tilburg) We can see hahanga stretching at the top all along the house, like a spine. Van Tilburg: "…the parts of the frame are the main and end rafters (oka), ridgepoles (ivi tika, which literally means spine, or hahanga) and purlins (kaukau, also applied to rafter)."

"…to enter a war canoe from either the stern or the prow was equivalent to a 'change of state or death'. Instead, the warrior had to cross the threshold of the side-strakes as a ritual entry into the body of his ancestor as represented by the canoe. The hull of the canoe was regarded as the backbone of their chief. In laments for dead chiefs, the deceased are often compared to broken canoes awash in the surf." (Starzecka) It appears, I think, that the path of the sun over the night sky very well could correspond to the hahaga, or backbone of the 'dead chief'. And then we see that a swordfish is called ivi tika. I think about the earlier part of the story when Hotu A Matu'a for the last time talks with his four sons and calls the youngest one a swift great shark. And yet earlier the dream soul of Hau Mea had named the 13th station "Tama, an evil fish (he ika kino) with a very long nose (he ihu roroa)". The evil fish with a very long nose ought to be a sword fish, not a shark. But the big verocious fish with a hare paega on his back had no sword on his nose. There must be two kinds of fish involved. The one with a sword on his nose should, I think, represent a cardinal point, probably 'dawn'. Because at 'dusk' there were two 'swords': "The Akkadians called it [Antares] Girtab, the Seizer, or Stinger, and the Place where One Bows Down, titles indicative of the creature's dangerous character; although some early translators of the cuneiform text rendered it the Double Sword. The one with no sword on his nose but a haere paega on his back probably represents the sun on his underworld voyage. To continue with the story about Ure Honu: "Ure sat out and caught eels, lobsters, and morays. He procured a great number (? he ika) of chickens, yams, and bananas and piled them up (hakatakataka) for the banquet to celebrate the new house. This sounds like magic growth resulting from aquiring the skull of Hotu A Matu'a. And it seems that Ure is in phase with the morning sun. A banquet must be held; presumably to return the boons, to return the best to the 'old bones' who have delivered. He sent a message to King Tuu Ko Ihu to come to the banquet for the new house in Vai Matā.

Here is the opposite to the 'very long nose' (ihu roroa) of the 'swordfish', a king with a snub nose (ihu) . Should that locate him to the evening? A foster child (maanga hangai) of Ure Honu was the escort (hokorua) of the king at the banquet and brought the food for the king, who was in the house. The men too came in groups and ate outside. When Tuu Ko Ihu had finished his dinner, he rested. At that time he saw the skull hanging above, and the king was very much amazed. Tuu Ko Ihu knew that it was the skull of King Hotu A Matua, and he wept. This is how he lamented: 'Here are the teeth that ate the turtles and pigs (? kekepu) of Hiva, of the homeland!' After Tuu Ko Ihu had reached up with his hands, he cut off the skull and put it into his basket. Out (went) the king, Tuu Ko Ihu, and ran to Ahu Tepeu. He had the skull with him. King Tuu Ko Ihu dug a hole, made it very deep, and let the skull slide into it. Then he cushioned the hole with grass and put barkcloth on top of it, covered it with a flat slab of stone (keho), and covered (everything) with soil. Finally, he put a very big stone on top of it, in the opening of the door, outside the house.

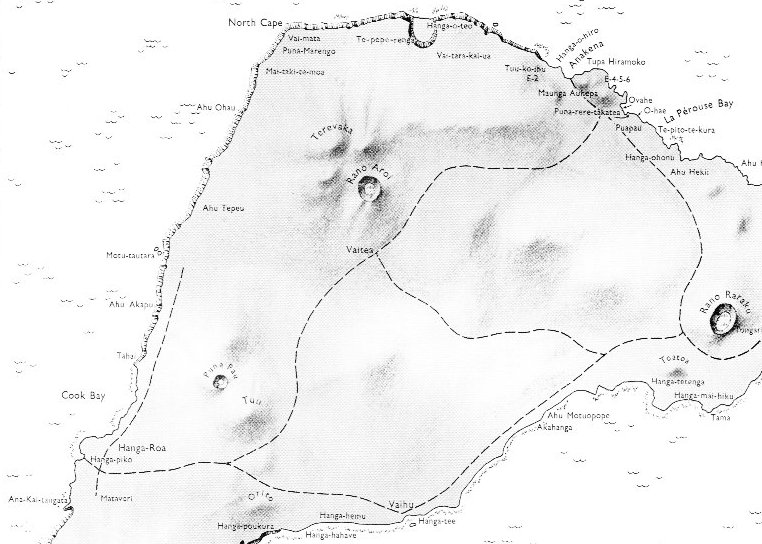

"The action moves from the site of Hotu Matua's grave (on the southern shore) to a hiding place near the northwest cape ('Vai Poko', TP:59, wordplay with puoko?) and then temporarily to the residence of Tuu Ko Ihu on the western shore. The more recent action takes place well within Miru territory. The three key locations - Akahanga, Vai Matā, and Ahu Tepeu - are all archeologically important cult centers." (Barthel 2)

Ure Honu looked around for his skull. It was no longer in the house. When he questioned those who knew, the foster child of Ure Honu said, 'On the day on which the banquet for the new house was held, Tuu Ko Ihu saw the skull. He was very much moved and wept, 'Here are the teeth that ate the turtles and the pigs (? kekepu) of Hiva, of the homeland!' When the foster child of Ure Honu had spoken, Ure Honu grew angry. He secretly called his people, a great number of men, to conduct a raid (he uma te taua). Ure set out and arrived in front of the house of Tuu Ko Ihu. Ure said to the king, 'I (come) to you for my very large and very beautiful skull, which you took away on the day when the banquet for the new house was held. Where is the skull now?' (whereupon) Tuu Ko Ihu replied, 'I don't know.' When Tuu Ko Ihu came out and sat on the stone underneath which he had buried the skull, Ure Honu shot into the house like a lizard. He lifted up the one side of the house. Then Ure Honu let it fall down again; he had found nothing. Ure Honu called, 'Dig up the ground and continue to search!' The search went on. They dug up the ground, and came to where the king was. The king (was still) sitting on the stone. They lifted the king off to the side and let him fall. Just like Ure had lifted up the house of Tuu Ko Ihu and let it fall down, so his men lifted the king and let him fall. In a way the house of the king is the king, I think. Furthermore, given that the king's house is a hare paega (or a similar construction) - which I am fairly certain of - I then would suggest that this house is the dome of the night sky. Ure personifies the morning sun, and he pushes this 'night roof' up to let in the light and thereby easily to be able to ascertain if the skull is there or not. Ure is also a lizard, which we will remember. We cannot follow all threads here and now. They lifted up the stone, and the skull looked (at them) from below. They took it, and a great clamour began because the skull had been found. Ure Honu went around and was very satisfied. He took it and left with his people. Ure Honu knew that it was the skull of the king (puoko ariki)."

In Barthel 2 he explains that this 'renaissance' of the skull of Hotu A Matu'a may have taken place about 10 generations after Tuu Maheke had hidden the skull: "Tuu Maheke and Tuu Ko Ihu, two outstanding figures in the history of the island, are linked by the royal skull and by similar actions (deceit, theft, and hiding). Still they are two entirely different ariki. One is the legitimate heir of the royal power, while the other is downgraded as ariki kē. This, in essence, seems to be the political meaning of the tale.

Ure Honu names 'Miru Te Mata Nui' (TP:63) as the legitimate owner (hoa puoko) of the skull. The justification for this is obvious. According to the traditions, Tuu Maheke returned to Hiva.

This meant that the second-born, Miru, (and his descendents) became the legitimate successor of the king. The fact that the people of Anakena support Ure Honu's claim against Tuu Ko Ihu means that the representatives of the Miru line from the traditional royal regions (Honga and Te Kena) moved against the leader of the line of Ahu Tepeu. It has ... been shown ... that the ariki Tuu Ko Ihu was not a legitimate king but a nobleman of considerable ability. He was the younger brother (mahaki) of 'Tupa Ariki' (Barthel 1961). Tuu Maheke's senior position is opposed by the junior position of Tuu Ko Ihu. The first one is successful in his dealings with the royal skull; the second one is not. The two protagonists are also linked by the term tupa (in Tuu Maheke's case, it is part of the name of his house 'Hare Tupa Tuu'; in Tuu Ko Ihu's case, it is part of the name of his older brother 'Tupa Ariki'.)

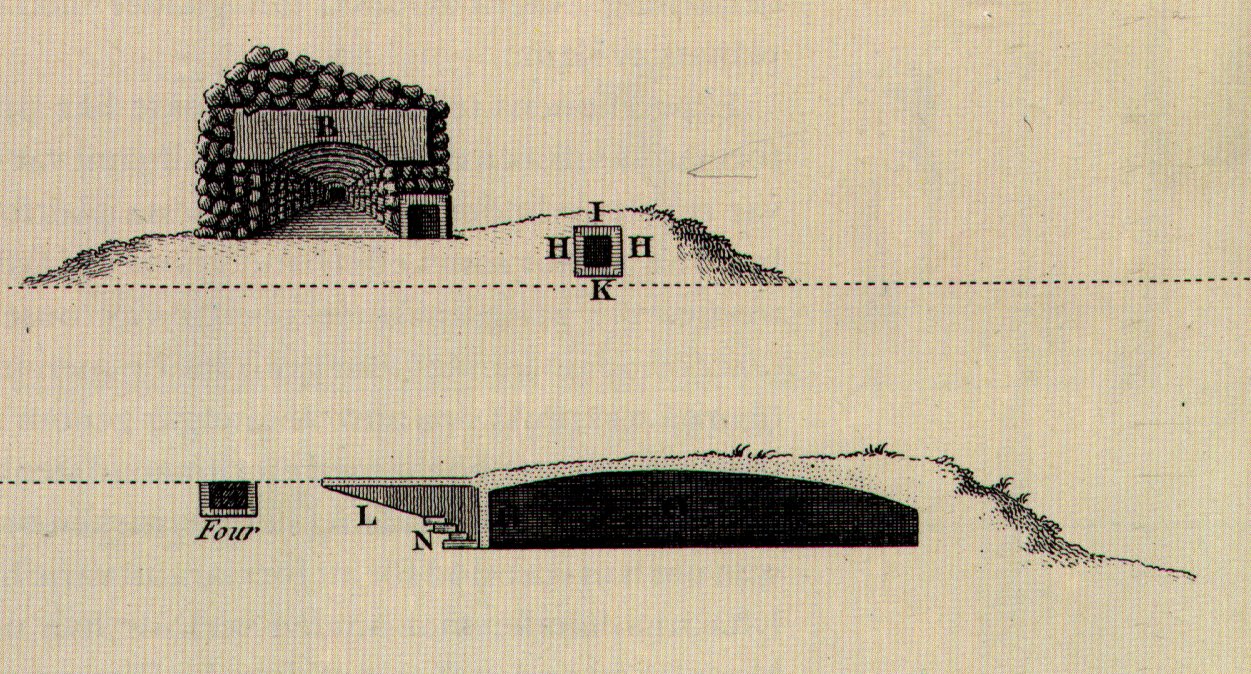

There seems to be an idea, in the tupa buildings, that one half should be up in the sun and the other half of the house down in mother earth. The entrances are square in form, like that in the hare paega on the back of the sun fish in the underground world. The parallel listing of the names 'Miru Te Mata Nui' and 'Tuu Ko Ihu' is based on the type of scheme underlying the initial segments I and III of the two most detailed lists of chiefs. Segment I begins after the break [a strange word; maybe Barthel too has understood ‘break’ = change of ‘season’; or is it perhaps the translator from German into English who has chosen the word ‘break’?] of the immigration, or, rather, the emigration from the old homeland, and segment III begins after the racial conflicts. They are listed in parallel positions:

The difference in time may be roughly ten generations. In a parallel position with the immigrant king is the 'lord of the oceans', after whom the tribe of the Haumoana in the southwest part of the island seems to have been named. Neither Vanaga nor Churchill has listed 'lord' as a possible translation of hau. Checking in Churchill's list over words from Tuamotus ('Pau.'), Mangareva ('Mgv.'), Tahitian ('Ta.') and Marquesas ('Mq.') - which he has sorted in that order so that no repetitions are needed - I find in the 'Pau' list: "Hau, superior, kingdom, to rule. Mgv.: hau, respect. Ta.: hau, government. Mq.: hau, id. Sa.: sauā, despotic. Ma.: hau, superior." I insert this new information in my list over Polynesian words. We do not know enough about the vocabulary of Easter Island in ancient times to exclude the interpretation of hau = lord. Chuchill: "Unbooked this people [the Polynesians] is, unlettered even, its words are in constant danger of loss. Where they remain in touch, one family with another, island with island, archipelago with archipelago - and this we know to have been in many instances the case in the period of the great voyages - the speech would tend toward the correction of its gradual loss, a common vocabulary would exist. But in the case of isolated and remote settlements the loss would progress with no possibility of reparation; each language would tend more and more to a greater bulk of vocabulary which elsewhere had fallen or had been forced into disuse. It does not surprise us that in four of these languages [= Mgv., Ta., Mq. and Rapa Nui] this individual and mutually incomprehensible stock of a primitive common speech should amount to two-thirds of the speech in use." We should probably 'read' that old king of Hiva, Hau Mea, as the 'Red Lord', a solar king like Hotu Matu'a I guess. And I start to think about the possible meanings of the words hotu and matu'a. Searching in the Rapanui lists of Vanaga and Churchill I cannot find hotu. Extending the search to the other Eastern Polynesian languages listed by Churchill, I find a very interesting item in the Mangarevan list: akahotu, the September season. Ta.: hotu, to produce fruit. Sa.: fotu, id. I insert this information into my own list of words. September stands for 'morning' and the sun in the morning should generate 'fruit', that we have learnt from the morning glyphs of these day calendars we are studying. Further confirmation of the probable meanings of the morning glyphs we find in:

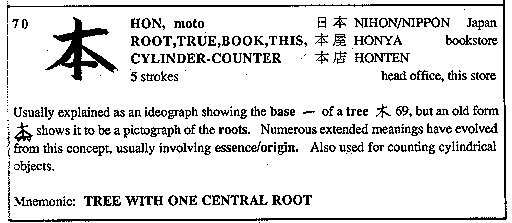

The root (aka) and the father (matu'a) are similar, necessary for the nourishment of the new young generation (hua) and it all takes place in the 'morning'. In the Japanese language aka means red and aka-tyan (‘the little red one’) = baby. In the land of the rising sun (Nihon) they have painted the sun red in their flag. An old variant of the sign hon ('root') explains that the short horizontal stroke is the remains of a picture of the root system of a tree. Though Henshall has converted this integrated system (as if systems could be anything else than integrated) into one central root:

Intrigued by this I pursue this trail further. In Churchill 2 we can read more about this word: "(a) aka, koa, stringy, fibrous; akoa na, ako ana, root (literal and figurative); aka na, ek, eka na, a relative, family connection (considered as root or offshoot from) ... (b) kaka naniu, the fibrous substance, like coarse cloth, that grows around the stem of the coconut ... In aka we find two words alike in form, aka a root and aka the vine. In general these two words have exactly the same form, but in Niuē and Viti they are distinguished and in practically the same way. The root signification in Niuē is expressed by vaka (vaka is also canoe); in Viti waka (canoe being wangga), and Rotumā va'a (vaka being canoe) are the same ... Our kaka is limited to Polynesia [i.e. not found anywhere in Melanesia] and restricted to the coconut fabric except in Tahiti [where] it extends to the breadfruit, the bamboo, and the sugarcane, and that among the Maori, who have not in their cooler land the coconut, it has possibly reverted to the primordial sense of anything fibrous." I.e. the 'root' of aka is 'fibrous', not 'red', not 'root system' and not 'beginning'. The connection with female is there, though, as fibres are their business. An overturned canoe (vaka) is also female in character. It seems reasonable for a canoe to sail along in the morning, when sun colours the eastern horizon red. Moses arrived as a baby in some similar vessel. Again, this points to the contrast between Anakena and Vinapu, which seems to have been all pervasive.

The son of the immigrant king and the son of the 'lord of the oceans' are equal in rank, based on the principle of seniority. Their respective younger brothers, Miru and Tuu Ko Ihu, are the last ones to come in contact, legitimately or illegitimately, with the skull of the immigrant king ... ... The last items mentioned in the Hotu Matua cycle have a dual nature: The rat is the spirit form of Hotu Matua (kuhane), and the painted skull is the bearer of the royal mana (puoko kotetu). [tetu = very large, very wide, huge (also: kotetu, nuinui tetu). Vanaga.] Together they are manifestations of the belief of later generations of Easter Islanders in the continuing presence of their emigrant king. This long excursion into the force of the skull should make us reevaluate the meaning of the type of glyph exemplified by Qa5-47:

This 'person' we are looking at - given that it is not just a way of illustrating the concept of growth - is he the sun as a king or as a god? (I think we can exclude the possibility of him being an ordinary man or woman.) What's the difference between a king and a god? On the other side of the earth (seen from us) the differences must be very small. As formulated in Islands of History: "Recapitulating the initial constitution of social life, the accession of the king is thus a recreation of the universe. The king makes his advent as a god. The symbolism of the installation rituals is cosmological." "The rationalization of power is not at issue so much as the representation of a general scheme of social life: a total 'structure of reproduction', including the complementary and antithetical relations between king and people, god and man, male and female, foreign and native, war and peace, heavens and earth." We should try to abstain from insisting on definitions in terms of entities, we must instead search for relations. We must try to wash our brains clean from such absurdities as entities - even gods and kings: “On one world view, if a particle of matter occupied a particular point in space-time, it was because another particle had pushed it there; on the other, it was because it was taking up its place in a field of force alongside other particles similarly responsive. Causation was thus not ‘particulate’ but ‘circumambient’.” (Needham 2) “Bruno’s world-conception approached almost more closely than that of any other European thinker to the ‘organic causality’ which ... was characteristic of classical Chinese thought. Bruno ascribes all motion, and indeed all change of state, to the inevitable reaction of a body to its environment. He does not conceive the action of the environment as taking place mechanically, but rather regards the onset of change in a given body as a function of the nature of that body itself, a nature so constituted as to necessitate that particular reaction to that particular set of environmental circumstances. He thus visualised the phenomena of the universe of Nature as a synthesis of freely developing innate forces impelling to eternal growth and change. Bruno spoke of the heavenly bodies as animalia pursuing their courses through space, believing that inorganic as well as organic entities were in some sense animated. The anima constitutes the raggione or inherent law which, in contradistinction to any outward force or constraint, is responsible for all phenomena and above all for all motion. The thought is extremely Chinese, even if vitiated by the characteristic animism of Europe.” (Needham 2) So let us proceed instead, to Qa5-48. We should start by examining this glyph in relation to the other parallel ones:

In H we may imagine a kind of continuation from the 'growth of the sun' in the 1st glyph to the two 'bulbs' in the 2nd glyph. The bottom 'bulb' should be the 'skull' and the top one the 'hua'. In P no such interpretation appears reasonable. There is no 'person' growing in the 1st glyph. In Q there should be some similarity in meaning compared with H, both texts appear to relate to sun as a 'person'. Maybe the difference is that in Q there is no hua? Another possibility is that the day calendar of Q has no e.m. Maybe that is the same thing as having no hua? When searching for answers we should remember that left in a glyph probably means 'tua' = that which has passed away. The right part (henua) is the sunlit part and the left part should be the dark part. But as we have seen, another possibility is to regard the bottom part as 'before' and the top as 'after'. At first I in my imagination saw (Qa5-48) as the sun in ‘egg-form’ diving down into the earth in the morning to reappear again later as a little newborn henua. In my mind I had turned the glyph 90o clockwise:

But that was clearly a mistake. Because early morning 'egg-form' then will be the sun at left; south of the equator he must be at right. To get him there we have instead to rotate the glyph 90o counterclockwise:

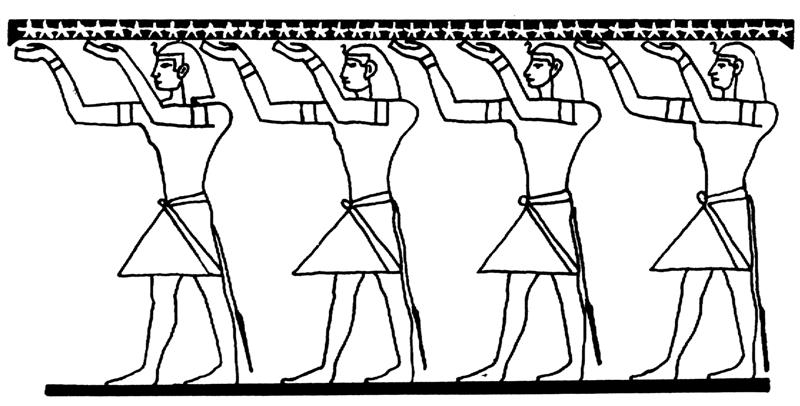

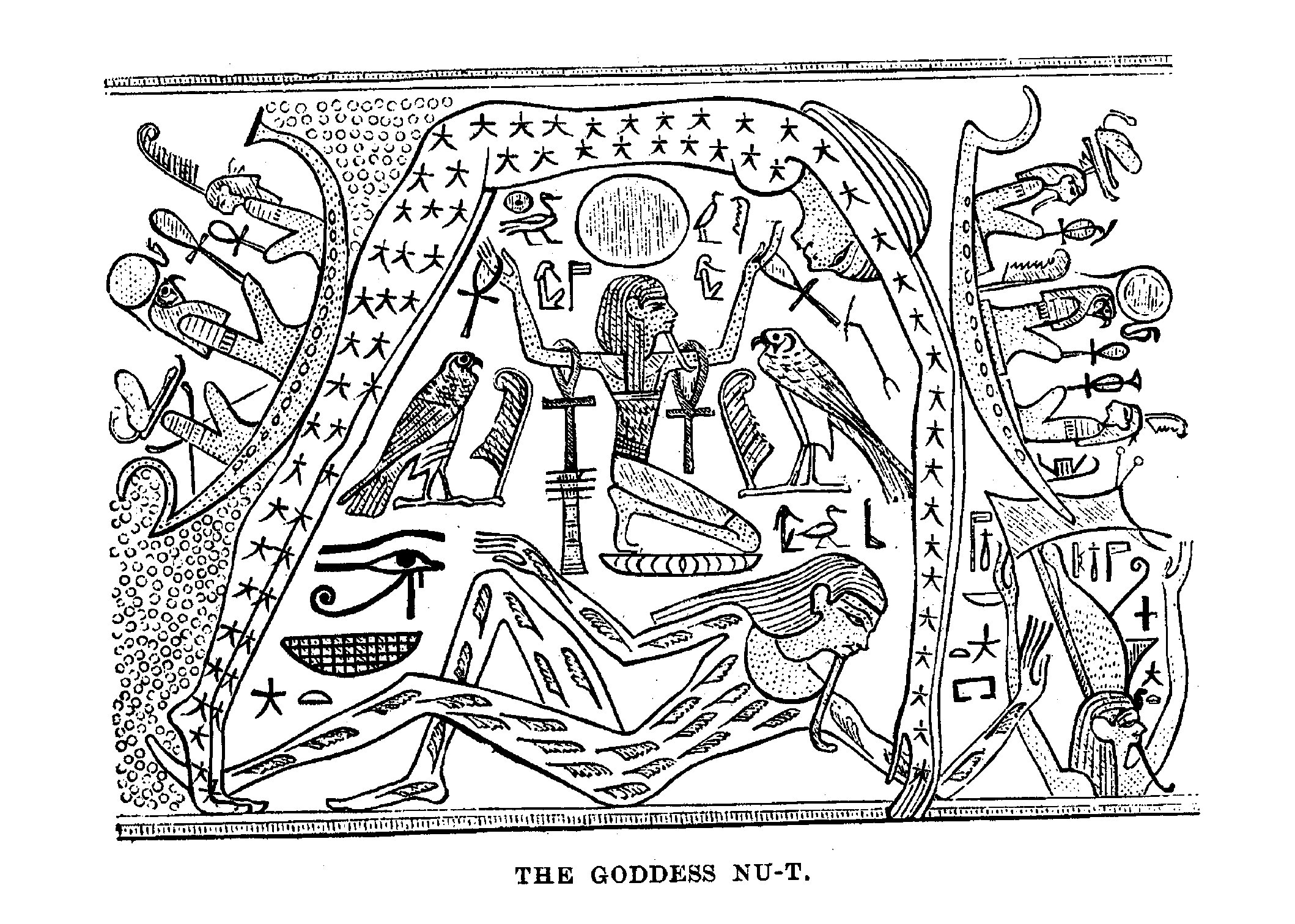

This gives us an interesting result. That part of the glyph which is henua now clearly is the sky, not the earth. I should have understood that earlier, because the henua glyph is straight and therefore male. The sky is male, not the earth. I am conditioned to read texts horizontally from left to right and then to jump downwards to the extreme left of the next line to continue there. The Easter Islanders also read their texts from left to right, but arriving at the end of a line the continuation should be found upwards and without any jumps. The 'front' for me is primarily to seek at right, whereas an Easter Islander primarily would search upwards. I guess this difference is partly due to the movement of the sky as observed from the movements of the stars: Near the equator (Easter Island) they rise from the eastern horizon and pass above the head to disappear later at the western horizon (like laundry inside a washing machine). The Chinese (also close to the equator) imagines rotatory movement as exemplified by the movement of a wheel, whereas western minds tend to imagine rotatory movement like the movement of a spinning top (and clockwise). To define the movement of a wheel up and down are essential, to define the movement of a spinning top the question of right or left immediately arises. So the little morning sun - still without visible flames - will rise in the east, go up into the sky, stay there during the middle of the day and then descend in the west in the evening. Seen from Easter Island the path of the sun is also from right to left, but that is a secondary observation. I think the idea of henua as the sky is important. No longer is it necessary for me to say 'sun-lit earth'. But if the new idea (of the glyph henua illustrating the sky) remains valid in my interpretation of the rongorongo texts, not being superceded by yet other ideas, it is a bit awkward to keep the name for this glyph type as henua. But so it will be, at least for now. We could e.g. always try to 'translate' henua in our minds as 'season' (in a wide sense). I don't need to write that this henua sky is lit up, because it always is, even during the night - when the stars are there - as seen in this Egyptian picture:

I suggest that the glyph type henua is showing a similar type of sky roof as that which the 8 hands are keeping up in the picture above. The hieroglyphic sign is pet, as seen coloured at top in this picture (also from Wilkinson):

The sky roof is pet, the earth (bottom) is ta and the staffs keeping the sky up were named was. In the ancient Egyptian language only consonants 'counted' and the sound of the vocals are therefore unknown. I.e. earth was 't', the same consonant which was added to a male name in order to signify his wife (e.g. Rā-t). The Egyptians saw the sky (pet) as straight and horizontal, evidently the earth (ta) too was considered straight and horizontal. The Babylonians realized that the earth could not be straight; a tower far away looked as if it had sunken down into the earth, the horizon cuts the bottom part off for distant viewers. So they imagined the earth as a kind of mountain. Old mountains have a convex surface and going uphill you therefore never see the top until you are there, and going downhill you never see the foot of the mountain until you are there. Thinking along these lines, I once again had a look at Aa1-20:

The earth and the moon are similar in shape (according to the Babylonian view). The shape of the sickle enlightened by the sun in this glyph is not the moon's. But it might be the shape of the earth. The Babylonians imagined that also the sky had a convex shape similar to the earth. But I think we have assured ourselves by now that the Easter Islanders had adopted the Egyptian straight sky view instead. Why are they different, these three glyphs (Qa5-48 and parallels) and what happens if we turn them all around 90o counterclockwise?

In H we recognize at left (sun's descent in the west) a similar direction (slant) and extension as the corresponding part of Q. The difference lies in the 'bulb' (probably hua) missing in Q. In P we have another type of 'light bulb' in the west than that in H. And in the east the 'root' (aka) of the sun is missing. For convenience sake I will call these two 'bulbs' aka (the morning 'skull') and hua (the evening 'fruit'). Evidently aka and hua are here (in these three texts) differently used by the artists. In H and Q we are not surprised to find them (because the sun in these two texts is depicted as a 'person'). In P, on the other hand, we should not misunderstand that sign in the west - it may signify something else than hua. Possibly it is a hole (through which the descending sun is going to disappear). But I doubt that, because such a hole should be circular in shape, not like an almond. Progress has been made, but we still have only incomplete understanding of these three parallel glyphs. I press on. In Mamari there possibly is a similar sign in Cb3-22 (on top of the 'waving wing'):

Presumably there is also a kind of progress from the similar sign in Cb3-21. In the Egyptian world - I thought - there was a hole in the east (left, face up) and a hole in the west (right, face down) through which the sun could enter and leave:

But the 'holes' are according to Wilkinson the two suns, morning and evening sun. And my ideas about they being holes in the ground I no longer am so certain about. Although in the Polynesian stories about Maui catching the sun to make him go slower there are sun holes in the ground, in old Babylonia they had holes in the sky for the sun to enter and leave. "Der Himmel wurde als ein Hohlbau vorgestellt ... Diese Höhlung ist nicht nur optisch und scheinbar, sondern vielmehr als eine wirkliche aufzufassen. Denn der Himmel hat Türen 'an beiden Seiten', so eine, aus der die Sonne des Morgens heraustritt ... und eine, in die sie des Abends hineingeht ... Da, wo wir den Horizont sehen, ist der Himmel zu Ende. Dort ist sein 'Grund' ... Diese 'Grundlage' wurde nicht etwa nur so genannt, weil sie sich unten befand wie die Grundlage des Hauses, sondern im vollen Sinne von 'Fundament' als das feste Fundament, auf dem der Himmel fest ruhte." (Ref. Jensen) After reevaluating the meaning of the henua glyph (from 'season' of 'sun-lit earth' to 'season' of 'light in the sky'), we should also reevaluate the meaning of this type of glyph:

It should mean the sky with two holes for the sun, one in the east and one in the west, not holes in the earth. But then another problem arises: If we turn this kind of glyph 90o counterclockwise and open the 'door' for the sun to arrive in the morning, then we get this picture:

We must have misunderstood its meaning. Instead of a 'door' opening in the morning the opening is now in the west, i.e. we should now imagine (at left) the remains of yesterdays sun, i.e. the 'husk' (kaka) of the old sun. Vocabulary may once more provide a test to see if it is possible that we have understood or not. I therefore search for words which are similar to kaka in Vanaga and in Churchill.

The step from fibres (kakaka) to baskets is short. Baskets (or nets) are associated with beginnings: "Originally the highly born family of the Sun, Moon, and stars dwelt in a cave on the summit of Maunga-nui, Great Mountain, in the ancient homeland. They were not at all comfortable in their gloomy home for they could not see distinctly and their eyes watered constantly. After the Sky-father had been elevated to his present eminence Tane decided that the celestial family would be happier in the sky, where they would serve the double purpose of ornamenting the naked body of Rangi and giving light to the Earth-mother. Since Papa had already been turned with her face toward the Underworld it is difficult to see how she would benefit by the illumination. Tane requested his brother Kewa to go to Maunga-nui and fetch the Sun, Moon, and stars. Kewa inquired, 'Who above on Maunga-nui is in charge of that family?' Tane replied: 'They are with Whiro-taringa-waru, Tongatonga (Deep Darkness; Milky Way), Tawhiri-rangi (Sky-sweep; God of Winds) and Te Ikaroa (Long Fish; part of the Milky Way, probably the dark rift), suspended within the house called Rangi-tukia (Occupied Sky).' When Kewa arrived at the base of Great Mountain he shouted to Tongatonga: 'The family of gods have finally decided that the children in your charge are to be taken hence and affixed to the front of Rangi-nui of Tamaku.' Tamaku, 'smoothed off', was the name of the second heaven from the bottom. Since the guardians of the high-born children had also been assigned the arduous task of procuring food for their charges they made not the slightest objection to relinquishing them to Kewa. Kewa and Tongatonga ascended the mountain and looking down from its great height saw the children frolicking gaily on the sands of Te Rehu-roa, the Long Mist. When summoned to the summit they obeyed immediately. Their mode of progression was extremely odd, for they were round like an eye-ball and climbed the mountain by rolling over and over, as they had no legs. When they reached the courtyard called Sky-mat they disappeared quite docilely into their house. Then all the guardians procured baskets in which to transport the family. There was the basket of the Sun, Chief of the sky; the basket of the Moon, the Year-builder; the basket of Autahi, Canopus, and the younger stars, and the basket of Wide Space for the multitude of small star children. The tiny stars were placed in the canoe Uruao, Cloud-piercer, which can be seen in the sky (Tail of the Scorpion), and the canoe was given into the charge of Tama-rereti, Swift-flying Son, as its navigator. He was enjoined to tend carefully the little star children lest they be jostled about by their elder brothers and some of them fall to earth. The whole celestial family was thus conveyed to the sky to be distributed artistically about on the surface of Rangi the Sky-father. Provision had to be made for the Sun, Moon, and planets to travel about on their ancestor, so Rongo-from-the-side-of-heaven and Rongo-of-the-great-side were sent aloft by Tane to lay out the ara matua, 'parent path', and its twelve divisions, in order that all the heavenly bodies might travel decorously without colliding with one another." (Makemson) We also remember the new year ceremonies in Hawaii: "The 'living god', moreover, passes the night prior to the dismemberment of Lono in a temporary house called 'the net house of Kahoali'i', set up before the temple structure where the image sleeps. In the myth pertinent to these rites, the trickster hero - whose father has the same name (Kuuka'ohi'alaki) as the Kuu-image of the temple - uses a certian 'net of Maoloha' to encircle a house, entrapping the goddess Haumea; whereas, Haumea (or Papa) is also a version of La'ila'i, the archetypal fertile woman, and the net used to entangle her had belonged to one Makali'i, 'Pleiades'. Just so, the succeeding Makahiki ceremony, following upon the putting away of the god, is called 'the net of Maoloha', and represents the gains in fertility accruing to the people from the victory over Lono. A large, loose-mesh net, filled with all kinds of food, is shaken at a priest's command. Fallen to earth, and to man's lot, the food is the augury of the coming year. The fertility of nature thus taken by humanity, a tribute-canoe of offerings to Lono is set adrift for Kahiki, homeland of the gods." (Islands of History) And this time, when I once again reread the cited passage, I for the first time notice that we have here a goddess Haumea, which sounds like a combination of hau tea and tapa mea. The night side of Haumea could be hau (tea) and the day side could be (tapa) mea. Together these two glyph types would then represent Mother Earth. Haumea is Mother Earth (Papa), but she is also La'ila'i, i.e. Ragiragi, 'sky-sky' (?). Earth and sky are close. Here both are women. In old Egypt the sky was Nut, also a woman. A few hours after having written this I discovered that in Churchill 2 there was a description of the meaning of the word la'ila'i: "[Efaté:] langilangi, to be proud, uplifted. Samoa: fa'alangilangi, to be angry because of disrespect. Tonga: langilangi, powerful, great, applied to chiefs; fakalangilangi, to honour, to dignify, to treat with great respect. Hawaii: lanilani, to be proud, to show haughtiness. Uvea: fakalai, to compliment, to adulate. Viti: langilangi, proud." Clearly there is here a net behind the back of the goddess Maat (picture from Wilkinson):

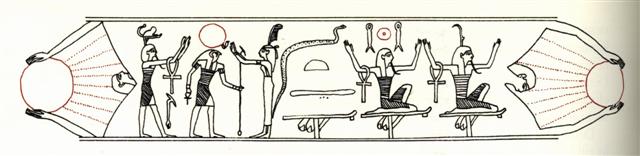

In another picture (from Wilkinson), where focus is on the ships of the sun travelling over the sky, we also can see this net:

But there is also a basket at the opposite end, which is not so evident, but which may be better seen in Lockyer's picture:

The hieroglyph for basket (nebet), is simplified and does not show the wickerwork (as in Lockyer's picture):

When the pharaoh was reinstalled at the beginning of a new period of reign this type of sign was used, 3 baskets oriented one way and 3 the opposite way (ref. Campbell 2):

A basket is a sign for the female (I believe), whereas the net is a sign for the male. Because beginnings are female (of course - giving birth) and therefore the end must be male. A net is the opposite of a basket. In a basket (properly prepared) you may carry water, never in a net. But perhaps the primary idea is that in a basket you preserve and protect (female characteristics), whereas a net is an instrument for activity and renewal (male characteristics). Nets in the west and baskets in the east. Wetness in the east and dryness in the west. But both baskets and nets are, kaka, 'fibrous' (in a wide sense). Back to the trail: The essential question is henua. Why did Metoro chose that word? He must certainly have known the meaning of this type of glyph. But perhaps he did not understand what the picture illustrated. Bishop Jaussen had persuaded him to just tell what the picture was, not tell what the text meant. In Churchill 2 we can read: "In Polynesia ... fanua means the land, from the mold at one's feet ... to the land in which one lives ... to the whole world of many lands ... " "I do not regard the use of fanua for town or village to arise from the rare house sense ... Rather does it seem to me to record the fact that our connotation of land is wider by far than is within the scope of these poor islanders. When one lives at the edge of the jungle and has to wage a steady fight against the voracity of the advancing timber the dread forest is not a land or a country, it is the dripping abode of the gods ever vengeful. Land is only the place of human habitation, hence a village or a town, the designation varying as foreign observers may choose to record their impression on a volymetric scale which is always loose." No sense of sky there. No sense even of 'season' (period of time as defined by different crops and activities). Yet I find the glyphs telling me that 'season' is the meaning of the glyph henua. And now, possibly, the picture in this henua glyph has been revealed as 'sky' (not 'earth'). We should listen to Metoro, but not obey him. His 'readings' give us help, but the rongorongo texts must be our guides. OK. If now the henua type of glyph illustrates the sky, then we should once again look at this type of glyph:

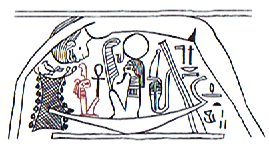

The Black Rat, or the sun / ariki in a dark 'season', might be the equivalent of Nut. We turn the glyph around 90o counterclockwise:

South of the equator the head will be shifted from east to west. The pictures of Nut above have her head at right, not at left (except the one with Maat; but hieroglyphs could be written either way, normally Nut seems to be shown with head at right). The head of Nut at right means west, seen from a point north of the equator (i.e. looking south, toward the equator). The basket was at her feet, a sign that we have analyzed the situation correct. Because the basket must be in the east. Now, from Easter Island seen, the head of the Black Rat (as seen in the glyph above) is in the west and his feet in the east, just as the feet of Nut are in the east and her head in the west. But in Egypt Nut was the night sky and it seems as if she had her feet and hands placed on earth, not in the sky - after all she was herself the sky. How do we explain this? I presume that she was the night sky, though I do not remember having read that from any of the authorities, they usually say just 'sky-goddess', without adding 'night'. But she was the daughter of Nu: "... the primordial ocean in which before the creation lay the germs of all things and all beings. The texts call him the 'father of the gods', but he remains a purely intellectual concept and had neither temples nor worshippers. He is sometimes found represented as a personage plunged up to his waist in water, holding up his arms to support the gods who have issued from him." (Larousse) For me it is selfevident that the chaotic primordial ocean and Nut must share the characteristic of not being in the light. Answer: On Easter Island we may consider the curved shape of the Black Rat to signify that part which is in opposition to the straight path of the sun during the 'day', i.e. the Black Rat = the path of the sun during the 'night'. North of the equator we find both the path of the sun and earth below the dome of the starry sky (Nut). South of the equator we are located on the opposite side, i.e. we look up from the watery darkness (Black Rat) to see the 'light' and 'earth'. "In the most general sense, the 'earth' was the ideal plane laid through the ecliptic. The 'dry earth', in a more specific sense, was the ideal plane going through the celestial equator. The equator thus divided two halves of the zodiac which ran on the ecliptic, 23 ˝o inclined to the equator, one half being 'dry land' (the northern band of the zodiac, reaching from the vernal to the autumnal equinox), the other representing the 'waters below' the equinoctial plane (the southern arc of the zodiac, reaching from the autumnal equinox, via the winter solstice, to the vernal equinox. The terms 'vernal equinox', 'winter solstice', etc., are used intentionally because myth deals with time, periods of time which correspond to angular measures, and not with tracts in space." (Hamlet's Mill) We check again with Qa5-48:

Here the 'head' ('skull' in a 'basket'?) is in the east. That is as it should be, because during the day things are reversed (as compared with the dark period). Possibly we should consider the lower shape similar to a 'determinant', i.e. a way of indicating the meaning of the henua part. In a way the true path of the sun (as schematically illustrated by the lower shape) has 'generated' the simplified picture that is the glyph type henua. There are several possible 'readings' of henua, not only a 'period of time' ('season'), but also - as here - the uplighted sky itself. The glyph type henua in a way may be regarded as the sky, yes. It shows that path of the sun which is current, i.e. the 'season' depends on the path of the sun. And then the land is dependent on the 'season', as Metoro says. That is my current hypothesis. On we move to Qa5-49; we cannot stay forever with Qa5-48 and definitive results are hard to reach by digging just in one spot:

Should we turn this glyph around 90o counterclockwise? No, I don't think so. Because the three vertical straight lines are indicating a close relationship with hau tea:

The hau tea glyph type, I imagine, shows the rays of the sun emanating from three spots: the horizon in the east (with a sun symbol), from the meridian (the peak) and from the horizon in the west (left). Basically, then, Qa5-49, illustrates the vertical sun rays. But what is the meaning? We can compare with the other similar glyphs in Q:

In the 2nd period the sun rays are more clearly depicted and we also get the message that at bottom we see the earth (like a mountain with a peak at noon). Here, in the '4th' period, three changes (relative to the glyph in the 2nd period) are seen: 1) The glyph has grown broader, which easily is understood as more light during the '4th' period than during the 2nd. 2) A 'roof' has been added, like a mirror image of the earth 'floor' at bottom. Possibly this is a way to construct a 'bridge' from the glyph in the 2nd period to the glyph in the '5th' period, a way to illustrate that the vertical sun rays (2nd period) are generating two 'seasons' (a.m. and e.m.) as demonstrated in the '5th' period. 3) The middle vertical sun ray is extended lower than in the 2nd period. This might be a way to continue with the message from the 2nd period: that we see sun rays (and that we have not - yet - reached the time for a change of 'seasons'). The vertical sun rays are integrated as the essential part of hau tea, a glyph type which should not be turned 90o counterclockwise. On the other hand, henua as path of the sun in the day sky should be horizontal, i.e. rotated 90o counterclockwise. There is room for misunderstandings here, when reading these slightly different glyphs. In the 1st period I think we should also imagine the glyph turned around:

At top we see a variant of henua with an indentation at right (east), i.e a sign that at right the eastern horizon (not straight because of the mountain) determines the beginning of this period. At the bottom of the glyph we maybe are seeing the earth 'floor' (abstract this time, therefore straight), which perhaps tells us that half of this period is still in the dark. The strange 'plumb' at right may now be percieved as a little henua, not yet born. But at the same time we can imagine that this henua soon will be growing up vertically, because we see the typical vertical sun-rays with the middle one extra long. In summary these four glyphs in Q presumably are visualizing a play involving the vertical hau tea and the horizontal henua. The concept of henua is arising in step with the sun and its rays. In Qa5-50:

we should turn our heads clockwise 90o to see the glyph as a picture:

Now can see the surface of the earth concave toward the sun, as if stretching herself up. The five short rays are like eyelashes of Mother Earth. I believe it significant that in the moon calendar of Mamari the glyph type for 'night' is the inverse of the tapa mea glyph type:

Turning this glyph around 90o counterclockwise we get:

The female night is symbolized by a glyph like the moon as seen at the equator in the early morning above the eastern horizon. For the moon this is a time of 'death', its last visible phase. The moon is rising in the east earlier every morning and soon she will be overcome by the sun. As Zehren has described it the moon is like a dying snake about to be fried by the rays of the sun. It seems as if there is a logic of polarity at work in the rongorongo texts. Opposites are symbolized by the polarity of sun versus moon / light versus darkness / day versus night / man versus woman / dryness versus watery / convex versus concave etc. “Freeman describres the dualistic cosmology of the Pythagorean school (-5th century), embodied in a table of ten pairs of opposites. On one side there was the limited, the odd, the one, the right, the male, the good, motion, light, square and straight. On the other side there was the unlimited, the even, the many, the left, the female, the bad, rest, darkness, oblong and curved.” (Needham 2) The logic of polarity 'created' a picture of the world as ordered (a cosmos), a moving total of experiences which varied cyclically and therefore predictably, creating a feeling of security. There possibly is a symbolism in numbers connecting the two opposites of sun and moon. In the Mamari moon calender we find 8 periods. This number may be connected with the fact that in Babylonia the dome of the sky was divided into 8 sectors, as seen in the cuneiform sign for 'sky':

For 'star' they used the 'sky' sign tripled:

"Der Himmel. Fast weitaus gewöhnlichste Ideogramm dafür ist

Fast allgemein hat man

in demselben, welches aus dem ursprünglicheren

bezeichnet wird.

Oppert indes hat behauptet, dass die Figur

Notably 'star' was depicted as 3 'sky' signs, which means that number 24 (= 3* 8) was also involved. On Easter Island the sun and the stars were similar concepts. (And indeed nowadays even we in the Western Civilization know that the sun is a star.) But 24 is also = 4 * 6, i.e. a way of signifying the course of the sun. We have seen that during the year the sun has 3 wives and that, I guess, is the formula 3 * 8 = 24. "The months were also personified by the Marquesans who claimed, as did the Moriori, that they were descendants of the Sky-father. Vatea, the Marquesan Sky-parent, became the father of the twelve months by three wives among whom they were evenly divided ..." Each wife, then, would have 4 months = 4 * 8 = 24 moon periods (as indicated by the Mamari moon calendar). Sun has number 6 and moon number 8. But those 6 means 6 double-months = 12 months. The structure with double periods maybe started by counting nights of the moon, noticing that the result was not good (29.5 not being a good result) and therefore doubling to reach 59. 59 was a good result because that meant 60 markers (one at the beginning and one at the end of each night period) had to be used. (And 6 * 60 = 360.) The last marker was equivalent to zero, because 0 described the full round. I think this way of thinking also explains the following two Chinese 'calendars' (ref. Needham 2):

The 'points of return' are those places which are '0'. The cycle of the lunar month has 7 periods, but 8 markers for beginnings and ends are needed. The diurnal cycle has 11 periods, but 12 markers are needed. We can count: 8 + 12 = 20 = the number of toes and fingers combined. 2 * 20 = 40. 360 / 8 = 45. 45 - 40 = 5. 8 * 5 = 40. I.e. 360 = 8 * 40 + 40. If you dislike odd numbers (like 45), then a way out is to count years in twos. And get 18 * 40 = 720. Add then those 2 * 5 = 10 which are needed to make the model agree with the 'real' year (with 365 days) and reach 730. If your still are not satisfied, because you know that the 'real' year is 365 1/4 days, you have to double 730 and add 1, reaching 1461. Which indeed is a 'magic number'. It would not be surprising if we were to find out that the 3 wives of the sun are illustrated as baskets in this picture:

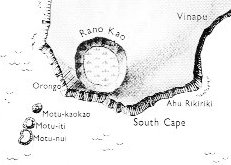

At left Pharaoh is leaving his three 'wives' of the ‘year’ which just has ended, at right he has the 'wives' of next ‘year’, that is what I think. Originally the 'year' was 30 years (according to some authorities), later the 'year' was shortened. Rejuventation perhaps was needed more often? Each 'basket' would be 120 days or a double moon 'season' (59 + 1 to 'change gears'), i.e. 6 (= 3 * 2) double moon 'seasons' for a year, quite in harmony with the 6 double sun 'seasons' (2 * 30 = 60 days) for a year. Then at the end of the year 5 additional days are needed to 'change gears' for both sun and moon. We must also - having reached so far in our reasoning - document the similarity (I doubt it is just chance) to the three islets outside Orongo:

They were the 'sons' (possibly male by consequence of being south of the equator) of Hau Maka:

This is the starting point. As we have seen, the path of the dream soul 'is' the path of the sun. Therefore these three islets represent the beginning of the year. I have found a glyph (Eb6-1) which presumably illustrates this 'station':

Here there is a gap (in the form of a missing henua) between old and new year, probably meaning that there are five nights which belong neither to the old year nor to the new year, nights which have no order (no henua), i.e. no foothold and through which you have to 'leap'. That is my interpretation for the moment. At midnight, therefore, presumably a new day starts. In the 'calendar of the night' we find (Qa5-34) confirmation:

There is a henua glyph in the middle of the night. Possibly we should read this glyph as a representation of 'day' and that a new day is beginning in the middle of the night (as when a new year is beginning in the middle of the winter). Possibly the old Chinese sign for 'root' is related to this subject. If we rotate 90o clockwise (north of the equator now) we get:

Three 'wives' at left (the 'roots') and a 'tree' (henua) pointing forward. What keeps the dome of the sky up during the night? The sun rays are not there. Answer: a 'pole' in the middle (just as when you raise the roof of a tent). Originally the glyph type henua may have meant a wooden pole. But as 'night' = hare paega, and as there are no vertical 'tent-poles' in the center of a hare paega, this important supporting pole must be horizontal. Instead we find it running along the center of the roof. It is the ridgepole, ivi tika ('spine'). We should finish this subject by asking who these 'handsome youths' were, "... the handsome youths of Te Taanga, who are standing in the water..."): "During my field work, questions about Taana yielded the following answer: Once he ruled a land called 'Hiva' or 'Ovakevake', where all spirits (akuaku) have their home.

Through the power of his mana he learned of the location of Easter Island and sent his three sons across the sea to the island. When his three sons approached the cliff 'Te Karikari' (on the outer rim of the crater Rano Kao), an evil sorcerer changed them into rocks. I remember that one meaning of karikari is 'bone joint', which seems appropriate here because one 'bone' is ending (at 'new year') and another 'bone' (henua) starts. There must be a joint, karikari, between two henua. A jealous relative on the maternal side, 'Riu', caused this to happen. The three sons of 'Taana' became the islets Motu Nui, Motu Iti, and Motu Kaokoa, which can be seen to this day. The map I have been using when relating about the kuhane of Hau Maka has the name Motu Kaokao (not Motu Kaokoa). I think Kaokoa is a misprint as otherwise (in Barthel 2) the name is Kaokao. The meaning of the word affirms this too:

The similarity to Ms. E is unmistakable. The three rocky islets off the cliffs of the southwestern part of Easter Island, once closely connected with the cult of the birdman, were considered the landmark of Easter Island and were called 'the three sons of Te Taana, who are standing in the water' (ko nga kope tutuu vai a te taanga) (Ms. E; TP:24; and the faulty ME:58). If one assumes that the form handed down in the local name is the original one, 'Te Taanga', then a sound change from 'ng' to 'n' has taken place in the other sources, as in fact can sometimes be observed in modern Rapanui." (Barthel 2) My expression 'leap' is of course influenced by the term 'leap year'. An ordinary year consisting of 365 days was ancient times divided up into 360 days + 5 extra days, and I regard these 5 extra days as structurally the same as the extra day needed every 4th year. But there is more to it: "The last house of the island king is called 'Ko Te Vare Te Reingataki' (TP:53) or, rather, 'Te Rei Ngatake', which I feel should be spelled as 'Te Reinga Take'. I was told that 'Te Vare' is a place directly on the rim of the crater (compare RAP. varevare 'steep, rugged'), while 'Te Rei Ngatake' is farther away on the outside. I strongly suspect that we are dealing with the well-known Polynesian term reinga, which indicates the 'jumping-off place for the souls' (MAO. reinga wairua; Mangaia reinga vaerua, see Hiroa 1934:198-199).

The fact that this is the final period of Hotu Matua's life and the location of his last residence at the edge of the crater, whose original name was 'Poko Uri' (literally, 'dark hole', wordplay with po kouri 'black night, dark underworld'), reinforces this interpretation. According to Arturo Teao, the assumed 'jumping-off place of the souls' is connected with 'Taki'; according to Leonardo Pakarati, it is associated with 'Take'. Since one might expect a reference to one of the designations of the island king, take, whose meaning will be explained later, is the more likely of the two. In connection with the jumping-off place of the souls at the outset of their journey to the beyond, 'Te Vare' may have been a term used to describe the condition of one who is dying (compare TUA. vare 'to lose consciousness')." (Barthel 2)

My choice of the word 'leap' (across those uncertain 5 days between old and new 'year') was influenced also by the idea of that 'death' which must arrive before 'birth'. There is a 'joint' for the quick movement between the old order (henua) and the new. The three islets imply 'birth', therefore there should be a place for 'death' close by.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||