|

TRANSLATIONS

After the presumed introduction to the night (in Pa5-19) we should be on more secure ground as thereafter we find glyphs which are parallel to glyphs in A, the meanings of which we already have discussed. In P, though, the tôa are sorted into three groups (depending on the number of 'arms'):

The pattern is balanced: We have altogether10 tôa, with the central group containing 4 tôa and the flanking groups each containing 3 tôa, together 6 tôa. By now we should appreciate that the central 4 group then also means IV (the place of 'moko') and that the flanking 6 tôa mean 'sun' (his 'going away' respectively his 'rebirth'). The 'end of sun' group (zero arms) contains 3 glyphs, whereas the parallel in Tahua has only 2 glyphs:

As to toa tauuru we had concluded: 'We then should note that number 4, connecting both to uru - breadfruit, skull - and to the earth beneath which the sun has sunken, is marked also in the two maro-glyphs:

The 'chicken feathers' are 4 + 4 = 8. And 8 is a sign for the moon (eight periods in a Rapa Nui month), a fact which should be used also for the periods of the night ... ... While tapa mea means 'reddish count' (or something like that), pictured as the illuminated sky cap, tôa tauuru probably means 'black count' (or something like that), pictured (I guess) as the night sky cup.' Number 8 is in P presumably arrived at by counting together the 4 'sharkfins' and the 4 'chicken feathers'. The word toa in Metoro's reading is still unclear though. We had earlier noted that noon was called raa toa. Another appellation for noon was raa tini.

Furthermore, there is moa to'a:

In moa garahurahu we remember ehu: (as in Metoro's e ia toa tauuru - ehu):

Maro meant June (the time of winter solstice). That maro appears at the beginning of the night calendar is somewhat disturbing - shouldn't it appear at the darkest time of the night? Or - considering the reversals occuring when we change the 'rule' from day to night - shouldn't Maro appear at the beginning of the night? The expressions raa tini and tini po (notice the reversed order) for the middle of 'sun' and the middle of 'darkness' may be understood in two different ways: 1. The middle of day respectively night = the middle of the light period respectively the dark period = the middle of the time from dawn to dusk respectively the time from dusk to dawn. 2. The middle of day respectively night = the middle of the periods in the 'day' calendar respectively of the periods in the 'night' calendar. Maybe 1 is different from 2 - maybe the 'day' calendar covers all 24 hours, and also the 'night' calendar 24 hours. That would make it easier to understand why in Tahua the 'day' calendar appears before the 'night' calendar and in H / P / Q in the opposite order - two altogether different calendars, not two parts of one calendar. It would also explain why the start and end of a 'day' calendar is 'coloured dark'. And it would explain why the start and end of a 'night' calendar is 'coloured light'.

The central group of 4 tôa would then be the 'true' night and we could perhaps reverse these glyphs:

The reversal is seen not only in the way gravitation makes nuku, maro and hua hang down but also in their locations at left instead of the normal right side of a main body of the glyph. The effect of gravitation is not identical with the effect of streaming water.This is evident in the way the 'stems' of the 'appendices' are bent (possibly also the 'thread' of maro):

This school of fishes give the impression of being oriented in the right direction (a pun from me). The direction 'right' for the fishes is 'left' from us seen. Sun rises in the east and advances towards the west during the day, moving counterclockwise south of the equater, i.e. towards left from us seen. This rotatory motion is presumably not seen as circular, but rather like an oval shape, perhaps corresponding to the shapes of uhi tapamea and tôa tauuru:

We here see something similar to the eyes of the falcon god Horus, his right eye (Ra = sun) with lashes of sunbeams and his left eye (Horus = moon) as in shadow. Day and night, 6 sunbeams for the sun and 4 moonbeams (strokes in the tail of the fish) for the moon. The 'moon' calendar maybe includes both day and night, because there are 6 'tôa' (divided into two groups of 3) enclosing the 4 'tôa' of the real night. I have put all these tôa inside citation marks, because they are not all of glyph type GD47 (tôa), only the first 3 of them are. The rest belong to what I (following Metoro) have named rau hei (GD64):

Rau hei means a hanged 'fish' (killed and sacrificed enemy):

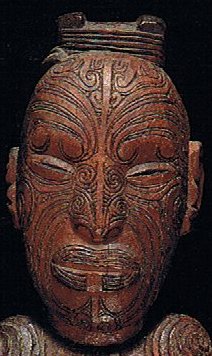

We note - en passant - that not only tini but also rau is used for counting high numbers. That fallen warriors were named rau hei is quite logical: leaves symbolize the many small tips at the ends of the branches of the great tree of life. The tree of life we also find as dividing the face (mata) of the Maori in the middle:

(Picture showing the head of a tekoteko, the gable apex figure of a small house. Ref. Starzecka.) We should compare this design with what we saw earlier in the ao:

The ideas are clearly identical. Not only do we find the central vertical line of the face marked as a tree (or rather the stem of a tree), but also we can see the signs of darkness above the eyes; in the ao as the wedgeshaped branches of the tree and in the tekoteko as ua-like curved tattoo lines.

We should here remember the painting of the storehouse with calendrical engravings on its gable. Probably gables - cfr tekoteko - means a place for calendars. Enlarging the figure on the top of the house in the background of the painting, we can see:

At 'noon' we find this 'person' with his central vertical line (the spine) dividing the period into two equal halves, illustrated with his arms - cfr the arm-links in the horizontal frieze:

The arms of a 'person' delivers one oval shape, the 'legs' another. I suggest that the ideas found in the Maori designs are quite similar to those found on Easter Island, both in its images and in the rongorongo glyphs. Therefore, we should understand the rongorongo system of writing as having been created by Polynesians; not by some tribe of South American indians. In a magazine I happened to read about the Aymará indians that they saw the past in front of them. The future is invisible and must therefore be located at the back side where there are no eyes. This for us peculiarly strange idea would be quite familiar for a Maori who is of the same opinion. "... The Maori word for 'the front of' is mua and this is used as a term to describe the past, that is, Nga wa o mua or the time in front of us. Likewise, the word for the back is muri which is a term that is used for the future ..." (Starzecka) I therefore suggest that this type of world view (such a fundamental trait must have determined other ideas too), connecting the Polynesians with the Aymará indians, is a proof of close contact between them in the past. So maybe the creation of the rongorongo system of writing equally well could be a feat of the Aymará indians. A proof of this statement, however, cannot be delivered in any other way than piecemeal. Moreover, if we discard our civilized mentality and return to what once was, the ideas found in the Maori designs and in the rongorongo glyph system are the same ideas that once were current all over the world. I was told as a child that if you dropped a knife on the kitchen floor, that meant a male visitor was due to arrive the same day. If you dropped a fork, then there was a woman soon to come and visit us. "fork ... pronged instrument for digging ... for eating ... diverging into branches, bifurcation ..." (English Etymology) "gable ... triangular piece of wall at end of a ridged roof ... orig. of twofold origin ... [1] ON. gafl ... mean[ing] 'fork' ... [2] Gr. kephalé head." (English Etymology) Forks were introduced at the kitchen table in modern times. Earlier it was spoon and knife. Therefore, shouldn’t I tell my grandchildren that if you drop a fork on the floor, then a beautiful bird will come to visit us. The kitchen fork has 'fingers' like the rays from the sun (whereas the pitch fork has the shape of Y). It cannot be a human being arriving, it must be a god or a chief - both of course with fiery feathers in their attire.

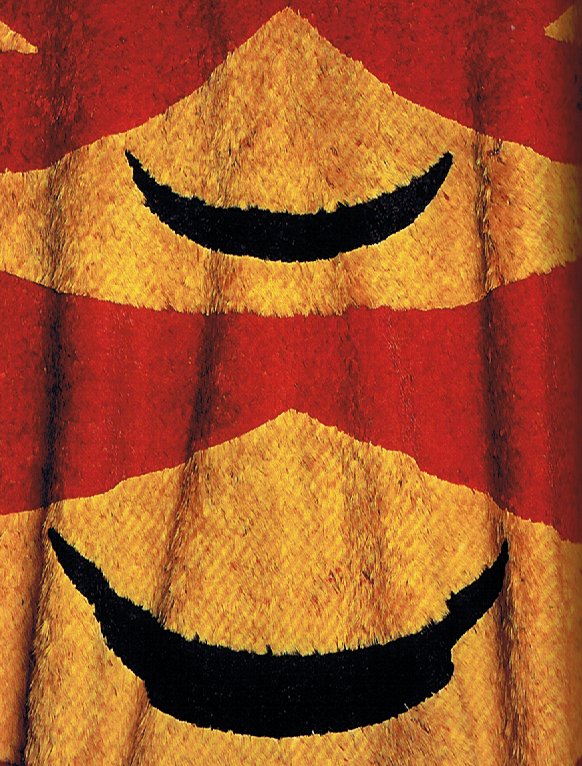

Feather cloak from Hawaii (D'Alleva) "pitch ... thrust or fix in; fix and erect ... set in order or in a fixed place; cast, throw ... inclination, slope ... highest point; position taken up ... (English Etymology) One piece in the piecemeal of proof (that Maori ideas are relevant when reading rongorongo texts):

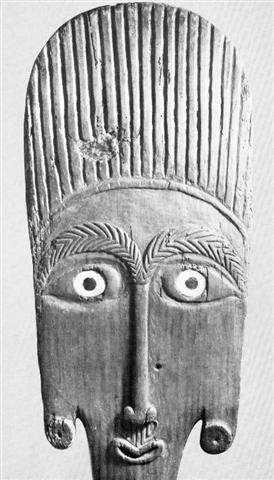

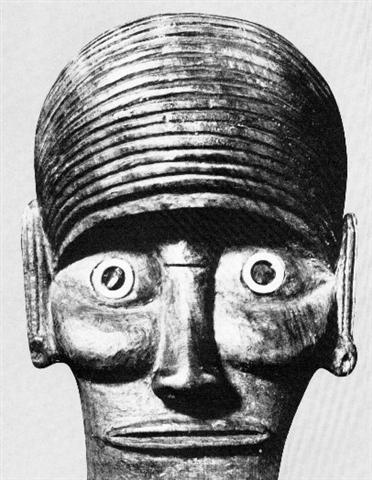

This is the lower abdomen and legs part of the tekoteko mentioned earlier. The knee caps are marked with two similar but different oval shapes (like eyes):

The right knee (left from us seen) has 6 oval small parts inside the oval, the left knee has 4 wedgeshaped small parts inside the oval. I guess this means 6 canoes inside the right oval and 4 canoes inside the left oval. The 'nighttime' canoes are seen from the side, while the 'daytime' canoes perhaps are seen from below. I am now convinced that tapa mea does not illustrate the day sky, but that instead we are looking at the right eye of Raá (the canoe of the sun).

From this I conclude that tôa tauuru probably is the left eye of Raá. Our eyes cannot meet the right eye of the sun or we would get blinded.

But we may guess that his right eye is similar in shape to the full moon. The 4 'canoes' in the left knee oval of the tekoteko figure, 'on the other hand', might be waning moon sickles. The shape of the sickle of the moon is not far away from the shape of the wedge on the storehouse roof. The sickle has bent 'rafters' while the storehouse has straight ones. The apex of the wedges probably indicate the 'full' moon respectively the 'full' sun. At (full) noon we saw GD15

In the Mamari calendar of the month we have at full moon:

The two supporters of Hotu Matu'a, Teke and Oti, are like the two end rafters at the gable of the house. According to Churchill it is not unusual with metathesis in the Polynesian vocabulary. I guess it is the Polynesian mentality which is the reason, their chiefs excelled in language juggling. "Words were like food for the Maori - riddles, word puzzles and proverbs were continously used and new ones invented daily, for as the saying states, Ko te kai a te rangatira, he kōrero ('oratory is the sustenance of chiefs')." (Starzecka) Here we have two words (teke and oti) with a similar meaning (of 'end'). From oti we easily proceed to kotikoti, cut off, (i.e. that oti once was - presumably - koti). If we then juggle kotikoti around we arrive at tikotiko, which sounds suspiciously close to tekoteko. Are there any words in the Rapanui language supporting the existence of tikotiko or tekoteko?

Hotu Matu'a was leaving the old land, in a way cutting of his bonds: "Hotu's canoe sailed from Maori to Te Pito O Te Kainga. It sailed on the second day of September (hora nui). The canoe of the king [ariki is used here incorrectly for tapairu ('queen')], of Ava Rei Pua, also sailed on the other side. They had attached the canoe of Ava Rei Pua to the middle of the canoe of Hotu [i.e., a double canoe had been built for the long voyage across the sea]. (E:53-74)" (Barthel 2) The 'middle' cannot be attached to more than one 'woman' I think. Therefore Hotu Matu'a had to cut off his old bonds. His new bonds connected to his queen. A canoe is also a kind of land. We should remember where Hotu Matu'a was buried: "The dead Hotu Matua is not taken to the royal residence at Anakena but to his last substantial land holdings along the middle segment of the southern shore. His burial place is not associated with an ahu, as might be expected, but is called 'Hare O Ava'. The description suggests that he was buried in a stone-lined grave in the shape of a box."

We should also remember Pua Katiki, the 'crater' at 'noon'. (Pua as in Ava Rei Pua and Katiki as a possible wordplay on kotikoti and tiki.)

"... pua 'flower', which is an old metaphor for 'woman'. Furthermore, in one recitation (Barthel 1960:847) this mountain [Pua Katiki] is associated with 'flat-nosed women'. Qualifying 'flower; woman' by katiki 'aura' suggests a wordplay on Tiki, the first human being ..." (Barthel 2) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||