|

TRANSLATIONS

Having thus

secured the

connection

between autumn

equinox and

hua poporo,

and once again

arrived at 180

(10) + 182 (13)

+ 3 = 365, this

time by way

of Mamari, the winding

trail goes on to

Ure Honu

and the skull of

king Hotu

Matua:

|

In Manuscript

E (according to Barthel 2) there are clues. Ure Honu had

a banana plantation and when he weeded it a rat appeared which lead him to the skull of King Hotu Matua.

The rat was the kuhane of the old solar king Hotu

Matua.

Ure means

lineage and honu means turtle. Ure Honu is the

name of the successor to the 'honu' (sun

king). Ure Honu, we can understand, is the new king,

because he found the yellow skull in his plantation. He had

received it by the aid of the kuhane (the black rat), he

had the good 'will' of the old king:

"... The

king,

wearing now

a short,

stiff

archaic

mantle,

walks in a

grave and

stately

manner to

the

sanctuary of

the wolf-god

Upwaut,

the 'Opener

of the Way',

where he

anoints the

sacred

standard

and,

preceded by

this,

marches to

the palace

chapel, into

which he

disappears.

A period of

time elapses

during which

the pharaoh

is no longer

manifest.

When he

reappears he

is clothed

as in the

Narmer

palette,

wearing the

kilt with

Hathor

belt and

bull's tail

attatched.

In his right

hand he

holds the

flail

scepter and

in his left,

instead of

the usual

crook of the

Good

Shepherd, an

object

resembling a

small

scroll,

called the

Will, the

House

Document, or

Secret of

the Two

Partners,

which he

exhibits in

triumph,

proclaiming

to all in

attendance

that it was

given him by

his dead

father

Osiris,

in the

presence of

the

earth-god

Geb.

'I have

run', he

cries,

'holding the

Secret of

the Two

Partners,

the Will

that my

father has

given me

before

Geb. I

have passed

through the

land and

touched the

four sides

of it. I

traverse it

as I

desire.' ...

" (Campbell

2)

|

|

We

can identify the black rat with Upwaut, the

wolf-god, the 'Opener of the Way'. There were no

wolves on Easter Island. |

|

The story about

Ure Honu

was introduced,

in the glyph

dictionary, just

a few pages

earlier:

|

"...

Another

year

passed,

and

a

man

by

the

name

of

Ure

Honu

went

to

work

in

his

banana

plantation.

He

went

and

came

to

the

last

part,

to

the

'head'

(i.e.,

the

upper

part

of

the

banana

plantation),

to

the

end

of

the

banana

plantation.

The

sun

was

standing

just

right

for

Ure

Honu

to

clean

out

the

weeds

from

the

banana

plantation.

On

the

first

day

he

hoed

the

weeds.

That

went

on

all

day,

and

then

evening

came.

Suddenly

a

rat

came

from

the

middle

of

the

banana

plantation.

Ure

Honu

saw

it

and

ran

after

it.

But

it

disappeared

and

he

could

not

catch

it.

On

the

second

day

of

hoeing,

the

same

thing

happened

with

the

rat.

It

ran

away,

and

he

could

not

catch

it.

On

the

third

day,

he

reached

the

'head'

of

the

bananas

and

finished

the

work

in

the

plantation.

Again

the

rat

ran

away,

and

Ure

Honu

followed

it.

It

ran

and

slipped

into

the

hole

of a

stone.

He

poked

after

it,

lifted

up

the

stone,

and

saw

that

the

skull

was

(in

the

hole)

of

the

stone.

(The

rat

was)

a

spirit

of

the

skull

(he

kuhane

o te

puoko).

Ure

Honu

was

amazed

and

said,

'How

beautiful

you

are!

In

the

head

of

the

new

bananas

is a

skull,

painted

with

yellow

root

and

with

a

strip

of

barkcloth

around

it.'

Ure

Honu

stayed

for

a

while,

(then)

he

went

away

and

covered

the

roof

of

his

house

in

Vai

Matā.

It

was

a

new

house.

He

took

the

very

large

skull,

which

he

had

found

at

the

head

of

the

banana

plantation,

and

hung

it

up

in

the

new

house.

He

tied

it

up

in

the

framework

of

the

roof

(hahanga)

and

left

it

hanging

there

..."

(Manuscript

E

according

to

Barthel

2) |

In ancient Egypt

the new year was

located at the

time when the

waters in the

Nile suddenly

came down from

Upper Egypt, and

it has been

described

earlier (at

niu) in the

glyph

dictionary:

|

"...

Instead

of

that

old,

dark,

terrible

drama

of

the

king's

death,

which

had

formerly

been

played

to

the

hilt,

the

audience

now

watched

a

solemn

symbolic

mime,

the

Sed

festival,

in

which

the

king

renewed

his

pharaonic

warrant

without

submitting

to

the

personal

inconvenience

of a

literal

death.

The

rite

was

celebrated,

some

authorities

believe,

according

to a

cycle

of

thirty

years,

regardless

of

the

dating

of

the

reigns;

others

have

it,

however,

that

the

only

scheduling

factor

was

the

king's

own

desire

and

command.

Either

way,

the

real

hero

of

the

great

occasion

was

no

longer

the

timeless

Pharaoh

(capital

P),

who

puts

on

pharaohs,

like

clothes,

and

puts

them

off,

but

the

living

garment

of

flesh

and

bone,

this

particular

pharaoh

So-and-so,

who,

instead

of

giving

himself

to

the

part,

now

had

found

a

way

to

keep

the

part

to

himself.

And

this

he

did

simply

by

stepping

the

mythological

image

down

one

degree.

Instead

of

Pharaoh

changing

pharaohs,

it

was

the

pharaoh

who

changed

costumes.

The

season

of

year

for

this

royal

ballet

was

the

same

as

that

proper

to a

coronation;

the

first

five

days

of

the

first

month

of

the

'Season

of

Coming

Forth',

when

the

hillocks

and

fields,

following

the

inundation

of

the

Nile,

were

again

emerging

from

the

waters.

For

the

seasonal

cycle,

throughout

the

ancient

world,

was

the

foremost

sign

of

rebirth

following

death,

and

in

Egypt

the

chronometer

of

this

cycle

was

the

annual

flooding

of

the

Nile.

Numerous

festival

edifices

were

constructed,

incensed,

and

consecrated;

a

throne

hall

wherein

the

king

should

sit

while

approached

in

obeisance

by

the

gods

and

their

priesthoods

(who

in a

crueler

time

would

have

been

the

registrars

of

his

death);

a

large

court

for

the

presentation

of

mimes,

processions,

and

other

such

visual

events;

and

finally

a

palace-chapel

into

which

the

god-king

would

retire

for

his

changes

of

costume.

Five

days

of

illumination,

called

the

'Lighting

of

the

Flame'

(which

in

the

earlier

reading

of

this

miracle

play

would

have

followed

the

quenching

of

the

fires

on

the

dark

night

of

the

moon

when

the

king

was

ritually

slain),

preceded

the

five

days

of

the

festival

itself;

and

then

the

solemn

occasion

(ad

majorem

dei

gloriam)

commenced.

The

opening

rites

were

under

the

patronage

of

Hathor.

The

king,

wearing

the

belt

with

her

four

faces

and

the

tail

of

her

mighty

bull,

moved

in

numerious

processions,

preceded

by

his

four

standards,

from

one

temple

to

the

next,

presenting

favors

(not

offerings)

to

the

gods.

Whereafter

the

priesthoods

arrived

in

homage

before

his

throne,

bearing

the

symbols

of

their

gods.

More

processions

followed,

during

which,

the

king

moved

about

- as

Professor

Frankfort

states

in

his

account

-

'like

the

shuttle

in a

great

loom'

to

re-create

the

fabric

of

his

domain,

into

which

the

cosmic

powers

represented

by

the

gods,

no

less

than

the

people

of

the

land,

were

to

be

woven

..." |

|

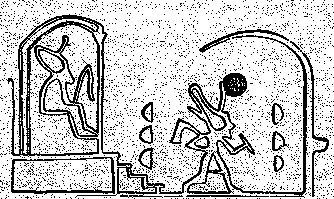

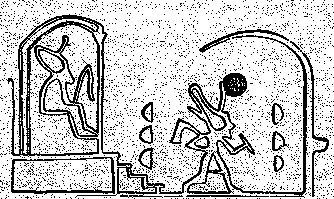

Then

follows

the

picture

above

and

the

text

about

Pharaoh

and

Upwaut. |

The Nile has

been mentioned

once more, in

the beginning at

manu rere:

|

2.

At

the

top

level

- at

the

apex

of

the

pyramid

-

the

'bird'

must

be a

bird

of

prey

and

like

a

king.

In

ancient

Egypt

there

was

also

a

special

type

of

bird

to

indicate

this,

the

benu

bird

(named

phoenix

by

the

Greeks).

According

to

Wilkinson

the

benu

bird

was

a

heron

(Ardea

cinerea

-

cǐnis

=

ashes)

and

'...

standing

for

itself

on

an

isolated

rock

or

on a

little

island

in

the

middle

of

the

water

the

heron

was

an

appropriate

image

for

how

the

first

life

appeared

on

the

primary

hill

which

arose

from

the

watery

chaos

at

the

time

of

the

original

creation.'

'Similarly

to

the

sun

the

heron

rose

up

from

the

primary

waters,

and

its

Egyptian

name,

benu,

was

probably

derived

from

the

word

weben,

to

'rise'

or

'shine'.

This

magnificent

wader

was

also

associated

with

the

inundations

of

the

Nile.'

But

herons

have

straight

beaks

in

order

to

be

able

to

harpoon

frogs

and

fishes.

The

picture

above,

also

from

Wilkinson,

instead

suggests

a

slightly

bent

beak.

'As

a

symbol

for

the

sun

the

heron

was

the

sacred

bird

of

Heliopolis,

which

became

the

mythical

phoenix

of

the

Greeks.

Without

doubt

through

its

association

with

the

descending

and

rising

sun

the

heron

was

comprehended

as

lord

over

the

royal

jubilee

of

rejuvenation,

which

was

staged

for

a

pharao

who

had

reigned

in

thirty

years.' |

We now can

identify the

'heron' with

Raven (in Haida

Gwaii):

|

Hereabouts

was

all

saltwater,

they

say. |

|

He

was

flying

all

around,

the

Raven

was, |

|

looking

for

land

that

he

could

stand

on. |

|

After

a

time,

at

the

toe

of

the

Islands,

there

was

one

rock

awash. |

|

He

flew

there

to

sit

... |

The Raven is the

trickster god

and therefore

equivalent with

Maui (who

was born in the

5th season at

solstice). The

trickster

personality must

be due to the

disorderly

(outside the

regular

calendar) time

between the

years (or

rather:

'years').

In the famous

sculpture The

Spirit of Haida

Gwaii it is

Raven who sits

at the stern and

manuvres:

The picture is

from Wikipedia.

The sculpture

exists in two

forms, a black

and a green

variant:

"The Spirit of

Haida Gwaii is

intended to

represent the

aboriginal

heritage of the

Haida Gwaii

region in

Canada's Queen

Charlotte

Islands. In

green-coloured

bronze on the

Vancouver

version and

black-coloured

on the

Washington

version, it

shows a

traditional

Haida cedar

dugout canoe

which totals six

metres in

length.

The canoe

carries the

following

passengers: the

Raven, the

traditional

trickster of

Haida mythology,

holding the

steering oar;

the Mouse Woman,

crouched under

Raven's tail;

the Grizzly

Bear, sitting at

the bow and

staring toward

Raven; the Bear

mother,

Grizzly's human

wife; their

cubs, Good Bear

(ears pointed

forward) and Bad

Bear (ears

pointed back);

Beaver, Raven's

uncle; Dogfish

Woman; the

Eagle; the Frog;

the Wolf, claws

imbedded in

Beaver's back

and teeth in

Eagle's wing; a

small human

paddler in Haida

garb known as

the Ancient

Reluctant

Conscript; and,

at the

sculpture's

focal point, the

human Shaman (or

Kilstlaai

in Haida), who

wears the Haida

cloak and woven

spruce root hat

and holds a tall

staff carved

with the

Seabear, Raven

and Killer

whale.

Consistent with

Haida tradition,

the significance

of the

passengers is

highly symbolic.

The variety and

interdependence

of the canoe's

occupants

represents the

natural

environment on

which the

ancient Haida

relied for their

very survival:

the passengers

are diverse, and

not always in

harmony, yet

they must depend

on one another

to live. The

fact that the

cunning

trickster,

Raven, holds the

steering oar is

likely symbolic

of nature's

unpredictability

..." (Wikipedia)

The one at the

stern who steers

is, we have

learnt, the weak

one (and I think

about

politicians -

all mouth and no

action). The

stronger ones

move the canoe

forward. 4 such

paddlers would

agree with the 4

arms raising the

sky roof:

The Raven is

black, a colour

in harmony with

the darkest time

of the year.

Yet, I remember:

|

...

In

Robert

Graves'

quest

for

understanding

he

arrives

at

identifying

the

lapwing

with

A:

Day

of

the

Winter

Solstice

- A

-

aidhircleóg,

lapwing;

alad,

piebald.

Why

is

the

Lapwing

at

the

head

of

the

vowels?

Not

hard

to

answer.

It

is a

reminder

that

the

secrets

of

the

Beth-Luis-Nion

[the

ABC

of

the

pre-latin

Ogham

alphabet]

must

be

hidden

by

deception

and

equivocation,

as

the

lapwing

hides

her

eggs.

And

Piebald

is

the

colour

of

this

mid-winter

season

when

wise

men

keep

to

their

chimney-corners,

which

are

black

with

soot

inside

and

outside

white

with

snow;

and

of

the

Goddess

of

Life-in-Death

and

Death-in-Life,

whose

prophetic

bird

is

the

piebald

magpie

... |

The magpie is

black and white

(suggesting both

halves of the

year), though in

the sunshine she

has all the

colours:

(Wikipedia)

I

write 'she',

because the

piebald bird

suggests

Taraga

rather than

Maui.

Pica pica,

her latin name,

'points' at

tara.

|

Tara

1.

Thorn:

tara

miro.

2.

Spur:

tara

moa.

3.

Corner;

te

tara

o te

hare,

corner

of

house;

tara

o te

ahu,

corner

of

ahu.

Vanaga.

(1.

Dollar;

moni

tara,

id.)

2.

Thorn,

spike,

horn;

taratara,

prickly,

rough,

full

of

rocks.

3.

To

announce,

to

proclaim,

to

promulgate,

to

call,

to

slander;

tatara,

to

make

a

genealogy.

Churchill |

The mystery of

colour (where

does it come

from?) certainly

is a subject of

myths.

"The Haida word

ghuhlghahl

corresponds well

to the Chinese

word qīng

and the Navajo

dootl'izh,

but not only to

any single word

in English. It

covers most of

the range which

English divides

with narrower

terms like blue,

bluegreen,

blueblack,

purple and

turquoise.

It is the colour

of the sunlit,

living world:

including the

blues and

indigoes of the

sky, the greens

and blues of the

sea, the summer

colours of

mountains, the

breathing greens

of needles,

shoots and

leaves, and the

iridescent

plumage of

several species

of birds.

It is also, like

qīng

and

dootl'izh,

the name of a

range of mineral

hues. It is

clearly distinct

from white

(which is

ghaada

in Haida) and

red (which is

sghiit),

but it impinges

on yellow, brown

and black. The

Haida word for

black,

hlghahl,

is also the word

for color in

general and

appears to be

the root from

which

ghuhlghahl

is derived ..."

(Sharp as a

Knife)

In the

Rapanui

language

ghuhlghahl

corresponds to

uri:

|

Uri

1.

Dark;

black-and-blue.

2.

Green;

ki

oti

te

toga,

he-uri

te

maúku

o te

kaiga,

te

kumara,

te

taro,

te

tahi

hoki

me'e,

once

winter

is

over,

the

grasses

grow

green,

and

the

sweet

potatoes,

and

the

taro,

and

the

other

plants.

Uriuri,

black;

very

dark.

Vanaga.

Uriuri,

black,

brown,

gray,

dark,

green,

blue,

violet

(hurihuri).

Hakahurihuri,

dark,

obscurity,

to

darken.

P

Pau.:

uriuri,

black.

Mgv.:

uriuri,

black,

very

dark,

color

of

the

deep

sea,

any

vivid

color.

Mq.:

uiui,

black,

brown.

Ta.:

uri,

black.

Churchill. |

Tangaroa uri

is the 1st month

of summer.

The most

detailed lesson

in the language

of Haida Gwaii

which Robert

Bringhurst

delivers (in

Sharp as a

Knife) is based

on the colour of

Raven. He must

have considered

it important:

|

Gyaan

han

lla

lla

suudas,

llagi

lla

xhastliyaay

dluu, |

Then

·

thus

·

him

· he

·

talking-action

·

him-to

· he

·

grasping-handling-the

·

when, |

As

he

handed

them

these,

he

said

to

him, |

|

"Dii

haw

dang

iiji. |

"Me

·

here

·

you

·

are. |

"You

are

me. |

|

Waa

ising

dang

iiji." |

That

·

there

·

too

·

you

·

are." |

You

are

that,

too." |

| |

|

|

|

Taj

xwaaghiit

laalghaay

gutgha

kunxhaawsi

un-guut |

Rear-of-house

·

toward-being

·

screens-the

·

together

·

corner-forming-did

·

top-along |

On

top

of

the

screens

forming

a

point

in

the

rear

of

the

house, |

|

giina

ghuhlghahl

stlabdala

ganhlghahldaayasi |

creature

·

blue

·

slim-being-many

·

jointly-moving-acting-did |

sleek

blue

beings

were

preening

themselves. |

|

lla

suudaasi. |

he ·

talking-acting-did. |

Those

are

the

things

of

which

he

was

speaking. |

"Not until much

later in the

poem ... will we

learn that these

sleek blue (and

by inference

blackish) beings

are definitely

ravens. But why

call ravens

slender and

bluegreen when

they appear to

many people as

well-fed,

muscular and

iridescent

black? This

question has

good answers in

the world of

natural history,

and equally good

answers in the

world of myth.

Skaay has both

feet in both

worlds, not one

foot in each.

It is worth

remembering

first of all

that blackness

and iridescence

are precisely

the qualitites

of the two

objects being

given to the

Raven - and the

sleek blue

beings enter the

narrative when

Voicehandler is

actually in

the process

of handing him

these things.

Skaay overlays

the images.

Iridescence and

blackness - two

qualities

embodied in the

raven - are

qualities the

Raven is about

to embody in the

world. Slimness

and

bluegreenness,

as it happens,

are basic

properties of

the Haida world

too ...

In the early

months of life,

the feathers of

ravens,

Corvus corax,

are dull and

brownish black.

At first molt,

four to six

months after

they are born,

they acquire the

new plumage that

looks iridescent

black to casual

orbservers but

proves on close

inspection to be

rich gunmetal

blue. A raven

that is slim and

blue is a

yearling ..."

(Sharp as a

Knife)

|