|

TRANSLATIONS

As the reader will have understood by now these pages do not yet pertain to the X-glyphs. I am still trying to consolidate the colossal amount of information amassed so far. A summary is not enough for such a consolidation. A summary is just a map over those rocks which seem to protrude up over the marshy messes. This consolidation phase must go further than that. We need some planks to walk on. Number 14 in the summary irritates me: 'The four calendars differ very much in the details: in the number of phases, in the number of glyphs and in the many various signs adorning the glyphs. All these differences tend to disturb the translation process rather than to facilitate.' I think this difficulty must be turned around to our profit and I believe we now have such a chance. From Bartel 2 we have learnt that: There are several possible translations for oraora as the reduplication of ora. Te Oraora Miro can be translated as 'the pieces of wood, tightly lashed together' (compare TAH. oraora 'to set close together, to fit parts of a canoe') and be taken to refer to the method of construction of the explorer canoe, while Oraora Ngaru means 'that which parts the water like a wedge', or 'that which saves (one) from the waves, that which is stronger that the waves'. Experience has taught me that parallel sequences of glyphs in different tablets have a tendency to carry the same message even when the glyphs are different. Therefore we should assume that the method in A of illustrating the phases of the day without using hau tea (GD41) is related to the other main difference between A on one hand and H, P, Q on the other, viz. the design of tapa mea (GD55) As an example we can use the 2nd period and regard just A and H:

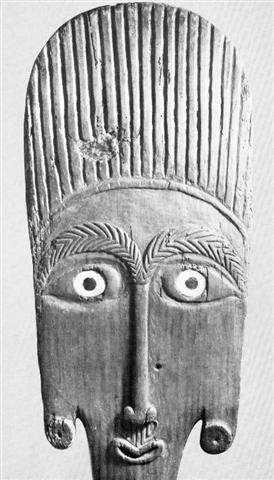

The 'sun-boat' - I propose - is here described in two different ways. In A we see a vaka (GD48) from above (or from below?) with '6 fiery feathers' (arranged in two groups) added, which converts the glyph type from GD48 (vaka) to GD55 (tapa mea). In H we instead have a sidewise view of the tapa mea canoe combined with a preceding glyph which might be oraora miro, two pieces of wood lashed together - though first hewed into a wedgelike form. Here we should recognize the non-perspective artistic perspective of the Maori: "McEwen's matching of stylised half-face profiles with corresponding full-frontal faces reveals that what appears to be a full-frontal face in Maori art is actually a split representation composed of two profile forms, a feature of Maori tattoo and carving first described by Léve-Strauss (1963:256-64) following Boas's analysis of the same phenomenon in North-west Coast American Indian art (Boas 1955: 223ff). Split representation allows all the essential features of a three-dimensional animal of human to be shown clearly without perspective distortion on a flat or relief surface or on a three-dimensional form different from the natural animal form. This obviously meets the need of a 'conceptual' art anxious to represent ancestor's correctly with all necessary details present. Split representation explains the deep v-shape between the brows of Maori faces, the frequently doubled nose and the convergence of lips at the centre of the face ..." (Starzecka) I think split representation also may explain e.g. the mouth on the Ao:

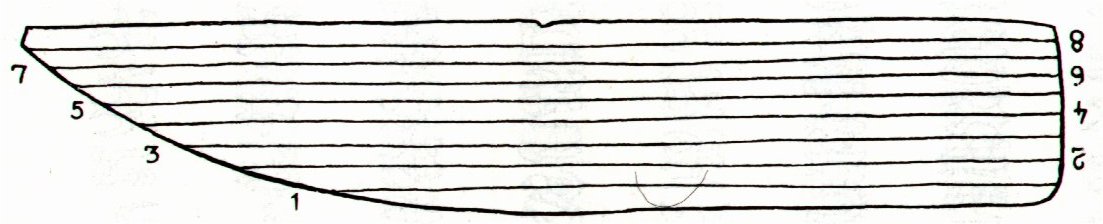

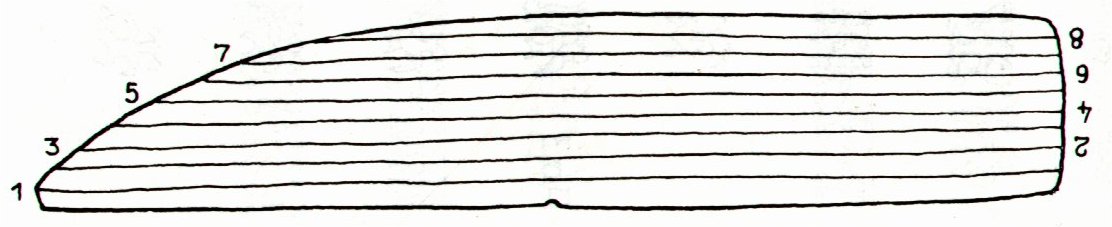

As to the planks for a canoe we have an example in form of a rongorongo tablet (S):

'This tablet has been used as planking in a canoe. Originally it was owned by Puhi 'a Rona, a tuhunga tá of Hanga Hahave, whose house 'was full of tablets and [he] scindered them at the call of the missionaries'. (Routledge according to Fischer.) '...a man named Niari, being of a practical mind, got hold of the discarded tablets and made a boat of them wherein he caught much fish. When the sewing came out, he stowed them into a cave at an ahu near Hanga Roa, to be made later into a new vessel there. [Nicolás] Pakarati, an islander now living [ca 1919], found a piece, and it was acquired by the U.S.A. ship Mohican.' The glyph type 'two planks lashed together' has two variants: without and with wedges. The variant with wedges does not occur in P (and neither of the two variants occur in A). A possible interpretation is that we should read Te oraora miro ('the pieces of wood, tightly lashed together') in P and Oraorangaru ('saved from the billows') in H and Q. H and Q do have 'two planks lashed together' without wedges, though, in this parallel sequence of glyphs (Hb3-30--34, Pb5-33--36, Qb6-120--126):

Interestingly we can see the eating gesture (kai) here too. If that means growing, then we can understand the en face figure in the middle as fully grown. Possibly the P middle 'man' holds a verical straight line to indicate 'middle', cfr Ha6-3:

At noon there is a change in the appearances of the 'lashed together planks':

In P we suddenly see sunrays instead of a canoe and in H and Q the canoes are smaller than before noon. The change into sunrays is not strange; the sun canoe in the sky is just in our imagination. But why should the canoe be smaller after noon? The answer may be that the sun is stronger during a.m. than during the afternoon haze. Another possibility is that there is another canoe (in our imagination) in the afternoon. What were the names of the other canoes, those that brought Hotu Matu'a with company to the island? "Routledge's informants still knew the names of the immigrant canoes (RM:278); they were given as 'Oteka' and 'Oua'. One Rongrongo text shows ua as the term used for two canoes, while RR:76 [Barthel's no. 76, GD111] (phallus grapheme ure, used in this case for an old synonym teka; compare TUA. teka 'penis of a turtle', HAW. ke'a 'virile male') tends to confirm the oral tradition with a transpositional variant (Barthel 1962:134)." (Barthel 2) Oteka and Oua probably is to be read as 'o teka and 'o ua, I think. We remember the names of the two assistants of Hotu Matu'a, Teke and Oti, words which we have came to associate with 'gables' (teko, tekoteko) and 'to expire' (koti, kotikoti, kotekote). But teke / teko is not the same as teka. As to ua we may at first may find these two main possible interpretations (I guess):

But the canoe name Oua probably is derived neither from 'o u'a nor 'o uá. Because - I guess - the mythic play of light and darkness would prefer names associated with ao and ua. As 'proof' of this I will put forward the meanings of the word teka:

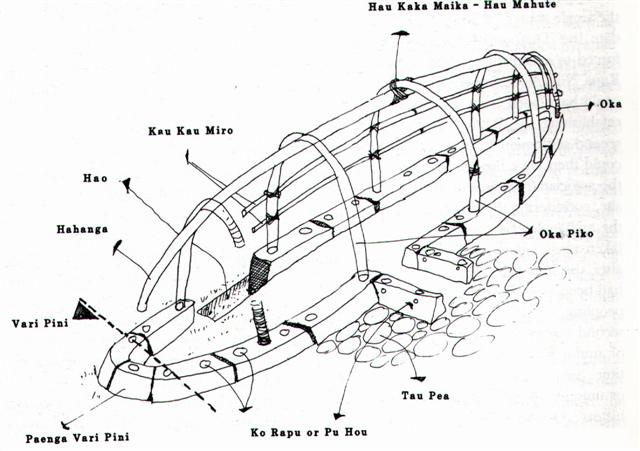

The 'crossbeam of a house' is a horizontal beam, and 'beam' we associate with sun-beams (in our efforts to translate the glyphs of the day calendars). The 'arrow' also indicates the sun. Finally we should consider the change of teka into te'a (in Samoa) and as a last step into tea (in Tahiti). Maybe hau tea is hau teka? The canoe (O)te(k)a would then be full (vakai) of light (tea) and represent the period from midnight until noon and the (O)ua canoe would represent the weaker vessel of light from noon and up to midnight. The derivative (?) words are: ûa - rain (etc) u'a - wave, surge (etc) uá - morning twilight (etc) all of which are 'female'. Does teka appear as the name of some crossbeam in hare paega? We can take a quick look:

No, there is no beam called teka. But we notice hau kaka maika - hau mahute (at the top of the picture). Immediately it becomes obvious that if hau tea equals hau teka, then surerly hau has the meaning of binding tight together.

We have arrived at the conclusion that hau tea (teka lashed with hau fibres) is close to Barhel's 'pieces of wood, tightly lashed together'. Oteka and Te oraora miro, one of the canoes of the explorers and one of the canoes of Hotu Matu'a, have closely connected names. Whereas we in a way can see wedges in the glyph type 'lashed together planks' of H and Q, these wedges are just in the form of the silhouette - the planks do not form a wedge:

Rather the planks forms the opposite shape, negative wedges, as we Westeners perceive the picture. But at noon time hau tea is depicted with a pronounced wedge pointing straight up (Ha6-9):

There is no indication that, in the Rapanui language, tea once was teka:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||