|

TRANSLATIONS

Parallel with writing here I am classifying all the glyphs in Aruku Kurenga according to type of GD. One of the glyphs (Ba6-2) - I happened to notice - has a unique strange semi-human appearance and its head is missing, which made me think of Oto Uta (Tautó). It could be a coincidence of course, but then I saw what Metoro had said and it became more interesting:

Two 'spooky' legs below what may be an 'earth' image and the arms have 'elbows' as if to denote the equinoxes. Not many words from Metoro were beginning with a Capital letter (the only examples I can remember are Rei and Raa), but here was clearly a very important glyph too. Possibly Toia originates from Tó-îa, i.e. 'he is Tó':

Often Metoro used the word koia, which possibly is ko-îa, some examples:

Is there a wordplay with Toia (Tó-îa) used instead of the normal koia (ko-îa)?

Polynesian wordplays tend to be complex and we should also think of Kukuru toûa (maybe tó-ûa). The egg-yolk is the sun, maybe, the missing head of Tautó.

We leave this problem. Instead, let us recall Ca7-14:

Red light in the east (mea) and red light in the west (hega) presumably once was the origin of the colour schemes all over the world. Therefore the two groups of triple marks probably are signs which indicate 'red'. We must remember this, because it may be useful when trying to understand other glyphs - maybe all similar marks indicate 'red'. The uhi tapa mea glyphs in the day calendars is a good example:

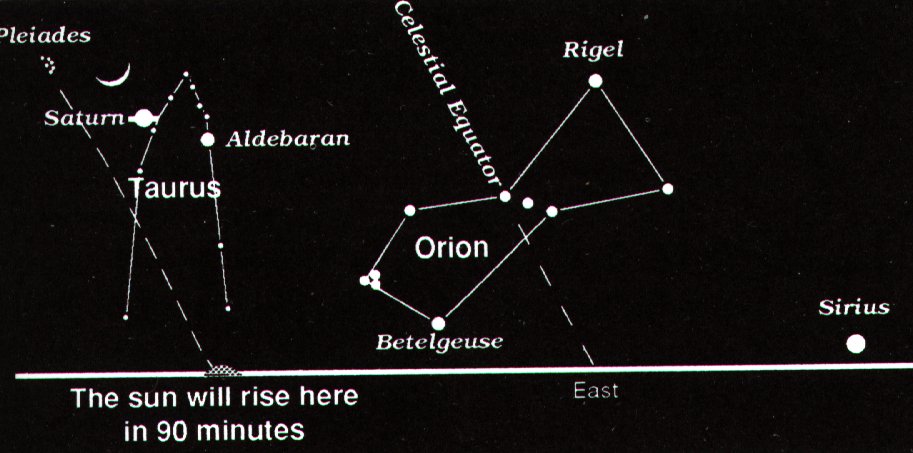

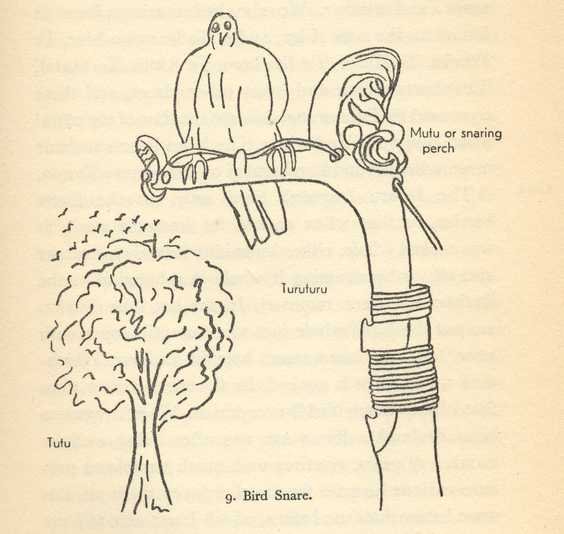

Evidently there are two sides (day and night) in the diurnal cycle (in contrast to the four in the yearly cycle). The 1st and 3rd sides of the hua have no marks of this kind, and whether we follow Atan and say that their colours are white (tea) respectively dark (uri) or whether we use the bird colours yellow (toûa) respectively dark (uri) may be of little interest. However, the 1st side may be marked by the sickle of the moon and then the colour of the moon (tea) is the correct reading of this side. The 3rd side has no mark at all and that means dark (uri). In Makemson - I am now moving on to another subject - we find: "Pewa-o-Tautoru, Bird-snare-of-Tautoru; the constellation Orion in New Zealand. The Belt and Sword form the perch, te mutu or te teke, while Rigel is the blossom cluster, Puanga, used to entice the unsuspecting bird. To visualize the bird-snare we must remember that Orion, as we see it in the northern hemisphere, is upside down to the view obtained from New Zealand where Orion stands in the northern sky." If we regard Easter Island as situated at the equator, then the rotation from head in the north to head in the south has been completed only halfway:

(Picture from Van Tilburg)

(Picture from Text Centre) The Pleiades all over the ancient world announced when new year was beginning. But on New Zealand also another model was used: "The Pleiades are situated 24° above the celestial equator at the present time on the circle which marks the northern limit of the Sun in declination [23°26′ 22″]. They rise soon after sunset on November 20, are on the merididan at sunset about February 20, and set in the rays of the setting Sun toward the end of April. 3 months from rise 'soon after sunset on November 20' the Pleiades are at the meridian 'at sunset' and then 'towards the end of April' - after another 2 months - they 'set in the rays of the setting Sun'. The movement of the Pleiades from the meridian to the west horizon takes an equal amount of time, I think, i.e. ¼ of the complete 12-month-cycle. But sun makes affirming observations impossible. Anyhow, from 'the end of April' (when they disappear from view as if being burned to ashes by the Sun) until November 20 (ca 7 months) the Pleiades cannot be seen in anywhere in the night sky (if the observation is done just after sundown) . If there were no sun disturbing the view, there would be ca 6 months visibility and ca 6 months invisibility. Sun destroys ca 1 month of the 'nika' period.

If we think of Tauono (the Pleiades) as having 'six stones' (tau-ono) and associate each stone with a 'season' corresponding to one month, then 6 could be understood as those 6 months when they in principle would be 'above' (in the night sky). If we think of the Pleiades as having 7 'stars', that could instead mean those 7 'months' when it is not practically possible to see them. Perhaps 7 indicates 'Moon' (nighttime) because the little 'suns' in the Pleiades do not shine during 7 'months'? Maybe those 7 'months' are refleced in Aa7-14 etc:

The glyphs are identical with the exception of Aa7-20, which has only half a 'moon sickle'. We remember that Ha5-28 has the same characteristic:

In both cases the explanation may be that sun is disturbing the possibility to observe (with the complete moon sickle meaning the night sky). We should here reexamine the two late winter month glyphs before light raises the sky:

While the 2nd glyph in H probably indicates that the nighttime observations are no longer possible because of the rising sun, the 1st glyphs in P and Q presumably indicate that the nighttime observations are reaching their end - no contact between leg and ragi in P and a complete rhomboid cycle sign below the toes in Q. The observation time could, however, be just before dawn - instead of just after sunset - and then the same 6 (respectively 7) 'months' of invisibility would also apply, though - north of the equator - with 'summer' instead of 'winter' as the period of 'nika': Thirty of forty days later they are visible on the eastern horizon just before dawn. The period of invisibility was a time of anxiety to the Indians of Paraguay who believed their ancestor, the Pleiades, to be seriously ill. The return of the cluster to the early morning sky was saluted with festivals of thanksgiving generally throughout South America. It is curious to find two peoples as far apart as the Indians of Paraguay and the Polynesians of Pukapuka calling themselves descendants of the Pleiades. If both early evening and late night were used for the observations, the Pleiades could be seen in ca 11 months. During the 12th month (of invisibility) the Pleiades perhaps went through 'recycling' (death and rebirth). But 'nika' probably was defined as the time of visibility given a certain observation point (just after sunset or just before sunup). The Blackfoot Indians of North America held solemn vigils at the beginning and end of the period of invisibility. Tribes of Brazil venerated the Pleiades as having special influence over human destinies, as did the aborigines of Australia who sang and danced to pleas and propitiate these fateful little stars. Peruvian Indians worshipped the Pleiades as having power over the growth of corn and the great Inca temple at Cuzco had a hall dedicated to the cluster. In Barthel 3 we learn of the Maya that they regarded the Pleiades as the grandmother of the Sun (with Moon as the mother of the Sun): "... Eine Wortspiellesung als 'ihr mit Wassertropfen gefüllter Leib ist der ausgebreitete Himmel' vermittelt dann die esoterische Information über die Spenderin des himmlischen Naß, sei es von der Plejaden-Großmutter, sei es von der mütterlichen Luna ... Plejaden wie Mond haben periodisch Zeiten der Unsichtbarkeit und sin dann vom Himmel 'verschwunden'. Wenn also die zur Großmutter wie zur Mond gehörige Schlange eine Affigierung T 13 = sat erhält, so ist das wohl auch durch den astronomisch vorgegebenen Zyklus beider Göttinnen zu verstehen ..." In the Polynesian tongue Matariki, the name for the Pleiades, is contracted from Mata-ariki, high-born or regal stars.

We must look for the explanation of the association of the Pleiades with the agricultural seasons on which early man depended for his chances of survival far in the past, for the cult of the Pleiades certainly dates from remote antiquity. Owing to the precession of the equinoxes the cluster is now 30° farther east of the vernal equinox than it was 2,000 years ago, when it was also 7° closer to the celestial equator. Some 4,000 years ago it was situated about 10° north of the vernal equinox. In that position their early morning rising ushered in the spring and the planting season in the northern hemisphere. Makemson says that 'thirty or forty days later' (after their disappearance 'in the rays of the setting Sun toward the end of April') the Pleiades 'are visible on the eastern horizon just before dawn'. The end of May / the beginning of June is the time when they reappear (in our time). Vernal equinox is at ca March 20 and if we shift the position of the Pleiades by 2 * 30° (to reach how it appeared 4,000 years ago) they should be at vernal equinox (end of May - 60 days = end of March). That they are 'farther east of the vernal equinox' consequently means that they have moved from spring equinox (as seen in the northern hemisphere) into early summer. '...The Akkadian Dil-gan I-ku, the Messenger of Light, or Dil-gan Babili, the Patron star of Babylon, is thought to have been Capella, known in Assyria an I-ku, the Leader, i.e. of the year; for, according to Sayce, in Akkadian times the commencement of the year was determined by the position of this star in relation to the moon at the vernal equinox. This was previous to 1730 BC, when, during the preceding 2130 years, spring began when the sun entered the constellation Taurus; in this connection the star was known as the Star of Marduk, but subsequent to that date some of these titles were apparently applied to Hamal, Wega, and other whose positions as to that initial point had changed by reason of precession. One cuneiform inscription, supposed to refer to our Capella, is rendered by Jensen Askar, the Tempest God; and the Tablet of the Thirty Stars bears the synonymous Ma-a-tu ...' Capella, the Leader (of the flock of seasons), announced (Messenger of Light) vernal equinox at a time ('previous to 1730 BC') when sun entered the constellation Taurus. There were several useful signs (stars) in the sky seen at a certain time of the year. '... The sun's position among the constellations at the vernal equinox was the pointer that indicated the 'hours' of the precessional cycle - very long hours indeed, the equinoctial sun occupying each zodiacal constellation for about 2,200 years. The constellation that rose in the east just before the sun (that is, rose heliacally) marked the 'place' where the sun rested. At this time it was known as the sun's 'carrier', and as the main 'pillar' of the sky, the vernal equinoxes being recognized as the fiducial point of the 'system', determining the first degree of the sun's yearly circle, and the first day of the year. (When we say, it was 'recognized', we mean that it was spelled 'carrier' or 'pillar', and the like: it must be kept in mind that we are dealing with a specific terminology, and not with vague and primitively rude 'beliefs' ...' '... In old Bablyonia the word 'umu' meant 'lion', i.e. the solar animal as in e.g. the Sphinx:

This picture (from Hancock 3) illustrates the spring equinox sky 10,500 BC with Leo preceding the sunrise. Due to the precession of the equinoxes in our days we have left Leo and are just on the verge to having Aquarius assuming that role, as half the precessional cycle is about 13,000 years. At the time of the Babylonians Leo ought to have been close to summer solstice (10,500 - 1/4 * 26,000 = 4,000 BC). So around 4,000 BC and at umu-time Leo should be the ruler ...' Whatever may have been the reason for the preëminence of the Pleiades cluster - and it was probably a combination of several reasons - it is certain that when men became increasingly alert ot the annual cycles of celestial phenomena, the changing altitudes and azimuths of the Sun, the lengthening and shortening of days and the corresponding variation in temperature, the slow march of the constellations across the sky, and realized the need of choosing a day on which to begin the yearly cycle of the calendar, they turned to the Pleiades for guidance. Undoubtedly the Polynesians carried the Pleiades year with them into the Pacific from the ancient homeland of Asia. With but few exceptions they continued to date the annual cycle from the rising of these stars until modern times. In the Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongan, Society, Marquesan, and some other islands the new year began in late November or early December with the first new Moon after the first appearance of the Pleiades in the eastern sky in the evening twilight. But according to Islands of History it was the full Moon which in Hawaii was the ideal: '... in the ceremonial course of the coming year, the king is symbolically transposed toward the Lono pole of Hawaiian divinity; the annual cycle tames the warrior-king in the same way as (e.g.) the Fijian installation rites. It need only be noticed that the renewal of kingship at the climax of the Makahiki coincides with the rebirth of nature. For in the ideal ritual calendar, the kali'i battle follows the autumnal appearance of the Pleiades, by thirty-three days - thus precisely, in the late eighteenth century, 21 December, the winter solstice. The king returns to power with the sun.7 7 The correspondence between the winter solstice and the kali'i rite of the Makahiki is arrived at as follows: ideally, the second ceremony of 'breaking the coconut', when the priests assemble at the temple to spot the rising of the Pleiades, coincides with the full moon (Hua tapu) of the twelfth lunar month (Welehu). In the latter eighteenth century, the Pleiades appear at sunset on 18 November. Ten days later (28 November), the Lono effigy sets off on its circuit, which lasts twenty-three days, thus bringing the god back for the climactic battle with the king on 21 December, the solstice (= Hawaiian 16 Makali'i). The correspondence is 'ideal' and only rarely achieved, since it depends on the coincidence of the full moon and the crepuscular rising of the Pleiades ...' Notable exceptions to the general rule are found in Pukapuka and among certain tribes of New Zealand where the new year was inaugurated by the first new Moon after the Pleiades appeared on the eastern horizon just before sunrise in June. Traces of an ancient year beginning in May have been noted in the Society Islands, but there is some uncertainty about the beginning of the year in native annals generally, at least as reported by missionaries and others, due perhaps to the desire to make the Polynesian months coincide with the stated months of the modern calendar. Vernal equinox should be the natural time for the year (or rather 'summer year') to begin. Once (some 4,000 years ago) the Pleiades had their heliacal rising at vernal equionox and that would - I think - be the reason for their importance. With the advance of the precession their importance could not just disappear and therefore new year was changed in various ways to suit the new position in time. With a 90° change summer solstice or winter solstice could be chosen according to whether the heliacal rising was observed north respective south of the equator. Alternatively the heliacal rising could be switched to a heliacal setting, observing the Pleiades just after sundown instead of just before sunup. That seems to have happened in many places, e.g. in Hawaii. On Easter Island, however, the Pleiades in recent times seems to have been observed to rise heliacally preceding the winter solstice: '...In Hawaii, the rising of the Pleiades was the signal for the beginning of the Makahiki major harvest festival which centered upon Lono (Rongo). For Rapa Nui, as for the Maori, the Mangarevans and the rest of the people of the Southern Hemisphere, the rising of the Pleiades is almost simultaneous with the Austral June solstice. The Rapa Nui calendar begins with the month of Anakena (the name of the landing site of Hotu Matu'a). Anakena was said by Thomson to mean August, but Métraux corrected that to July. Taking into consideration the conflicting evidence of the timing of Orongo ceremonies and based upon consultation with noted Pacific astronomer Will Kyselka, I think it is probable that the Rapa Nui ritual calendar, as that of the Maori, Mangarevans, Samoans, Tongans and other Polynesians began in July following the rising of the Pleiades ...' '... The Orongo rituals are thought to have begun in the AD 1400-1500s, and the use of Orongo as a ritual site intensified some fifty years later. If we take AD 1500 as a baseline, we find that the sun's declination was 23o26', while the declination of the Pleiades was 22o37'. This means that the Pleiades led the sun into the sky by about two hours, and that the two risings were over the same geographical feature a mere 0o49' apart. The ethnographies do not mention Orongo as a site from which the skies were watched. Let us presume however, on the basis of the site's special qualities and uses, that the old men may have watched the skies from Orongo. In the year AD 1500, they would have seen the Pleiades at 18o above the horizon at the end of astronomical twilight on hua, the twelfth night of the moon in the Rapa Nui month of Te Maro (The Loincloth). The Rapanui word hua means 'the same, to continue' and 'to bloom, to sprout, to flower', with a germ sense of both plants and human progeny growing and thriving ... The rising Pleiades led a twinkling procession of bright stars into the sky: Aldebaran first, then the stars of Orion (called Tautoru by the Rapa Nui). Sirius (Reitanga in Rapanui), at a declination of 16°42', is the brightest star in the sky on this and every other morning, and travels a path that takes it over the centre of Polynesian culture, Tahiti. The Pleiades set at 2:00 pm in the afternoon of that day and in the direction of the solstitial sunset, but the event was not visible. If the sunset was viewed from Poike it would have taken place in the direction of Anakena, the name of the first month of their calendar, the landing place of Hotu Matu'a, the birth place of the island culture and the traditional home of the ariki mau ...' In view of the almost universal prevalence of the Pleiades year throughout the Polynesian area it is surprising to find that in the South Island and certain parts of the North Island of New Zealand and in the neighboring Chatham Islands, the year began with the new Moon after the yearly morning [heliacal] rising, not of the Pleiades, but of the star Rigel in Orion. Such an important difference can be explained only on the assumption that the very first settlers from the west brought the Rigel year with them, perhaps from New Guinea or Java of some other land 10° south of the equator where Rigel acquired at the same time its synonymity with the zenith. On Easter Island (located at 27°03' S) the zenith star could have been regarded as Ana-mua, 'Entrance Pillar' (Antares). The star today has a declination of 26°15' and 1000 years in the future it will be at 27°31', i.e. around 2,600 A.D. Antares will be a perfect zenith star for Easter Island. Colonists who arrived in New Zealand from Central Polynesia during the Middle Ages and intermarried with the tangata whenua, 'people of the land', found themselves between the horns of a calendrical dilemma. They must either convert the aborigines to the Pleiades year beginning in November-December or themselves adopt the Rigel year [together with heliacal rising observations] and bring down the wrath of their ancestors on their own heads. That there resulted a long and passionate struggle on the part of both the invaders and the invaded to retain their own the integrity of the sacred year of their traditions can hardly by doubted. The outcome of the conflict proved that the institution of the land was too firmly established to be changed. While some tribes retained the Rigel year in its entirety others effected a compromise by retaining the Pleiades year but commencing it in June. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||