|

TRANSLATIONS

42 - that is the year when I was born. But the number haunts my mind for another reason: The explanations I have given so far are not satisfactory. The ancient Egyptians had 21 + 21 = 42 (as the number of judges in the Hall of Two Truths). I have guessed that 42 + 42 = 84 (as the number of nights in the difference between 364 and 10 * 28). These two 42:s cannot be the same. To think about 42 as 6 * 7 does not lead anywhere, but to think about 42 as 7 * 6 leads in the right direction. Anciently they approximated π = 3 (which may be the origin to the concept of 3 wives of the sun). Twice π then becomes 6 (the number of the sun) and a hexagon with 6 equilateral triangular 'flames' is the natural symbol for the sun:

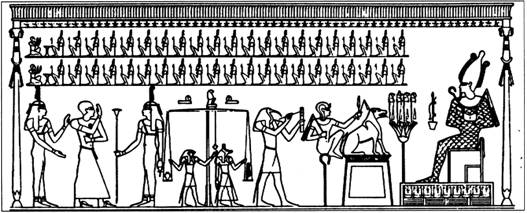

We can see that the symbol is constructed from two equilateral triangles, one 'ascending' (male) with apex up and one 'descending' (female) with apex down. The problem then becomes how to harmonize sun and moon. They do not move in the same orbits. 42 is the secret which solves the problem. We have seen that 13 months (à 28 nights) is close to a year, giving 364 nights. Sun's number 6 is not commensurable with that. But if we add one 'flame', increasing 360 to 420, we have a match: 14 * 30 = 420 = 15 * 28 This explains the 'hidden' a in the 8th line of Cuntisuyu. We should count 14 and 15 'at the same time'. It also explains why those who assisted Osiris in judging the souls of the dead were twice 21. Beyond the solar year we find the Hall of Two Truths (both the truth of the sun and the truth of the moon):

7 * 30 = 210 = 15 * 14. Does this 'halfway station' indicate the station of Tavake? One month after midsummer, in August, Kuukuu will meet with his destiny. Motu Tavake is number 7 in the Vanaga islet list: '... around the island: Motu Nui, Motu Iti, Motu Kaokao, Motu Tapu, Motu Marotiri, Motu Kau, Motu Tavake, Motu Tautara, Motu Ko Hepa Ko Maihori, Motu Hava ...'

6 they were the explorers - as the flames of the sun (Hotu Matu'a). Can we understand the daytime calendar of Tahua the same way? In the table below we see 10 periods:

I have painted blue for the 1st and 10th periods because they have the sign 2, and without doubt are outside the regular daytime. The first four redpainted periods (2-5) correspond to the four 'ascending' toko te ragi in spring. Noon (5 - 6) is a time for change and turnaround. The Y-sign may allude to the nesting site of the White Tern: '... this small tern is famous for laying its egg on bare thin branches in a small fork or depression without a nest. This balancing act is a predator-avoidance behaviour as the branches they choose are too small for rats or even small lizards to climb. Safe from predators, but still vulnerable to strong winds, the White Terns are also quick to relay should they lose the egg. The newly hatched chicks have well developed feet to hang on to their precarious nesting site with ...'

Sun 'dies' is dead in the 9th period (or 8th is we discard periods nos. 1 and 10):

Ure Honu lifted the side of the hare paega to have a look inside. Light was allowed in, and on the side where he had his hands it was lighter than on the side still lying on the ground. There the shadows still had a place. The spine of the hare paega was no longer in zenith but had shifted towards the shadowy side. "Chicken played an important role even in death ceremonies. When a birdman (tangata manu) died, five roosters were tied to each leg, and so strong was the taboo attached to them that only another birdman could remove them (ME:339). One recitation mentions one black hen and one small red hen in connection with the placing of the corpse on the platform during the death ceremonies (Barthel 1960:854; or differently, Campbell 1971:404). For further details regarding this theme, we are indebted to the Metoro chants:

(Barthel 1958:180) The three names mentioned at the end, which belong to chickens tied to the legs of the corpse, can be only partially interpreted. Moa uha pu seems to refer to a laying hen. Moa tengetenge is difficult to translate; my informants understood it to mean 'un gallo que siempre se mueve'. The same term appears in the Metoro chants parallel with a 'bird who lifts himself toward the sky and the abundance of rain' (manu huki ki te rangi ma te ua roa) or to a 'bird who inclines toward the stars' (ko te manu noe mai ki te hetu). This suggests the idea of a soul bird or a companion in the realm of the dead. Moa pu is mentioned in a different context, together with the red tapa that also plays a role in the death ceremonies. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that the dead person lying on the platform is compared to a 'rooster, who flies toward the stars' (moa rere hetuu). Here the night sky is an allusion to the world beyond." (Barthel 2) This flood of new relevant information cannot be digested immediately. We will remember, though, that toga apparently sometimes has the meaning 'wooden platform' (for dead chiefs). Probably Metoro meant that at Aa1-33 (ma te toga tu):

Possibly also, the reversed tapa mea with just 5 marks in Aa1-34 (te tapamea) is referring to 'the red tapa that also plays a role in the death ceremonies:

I have localised where Metoro said the words hupee hia etc, it was when reading Aruku Kurega:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||