|

TRANSLATIONS

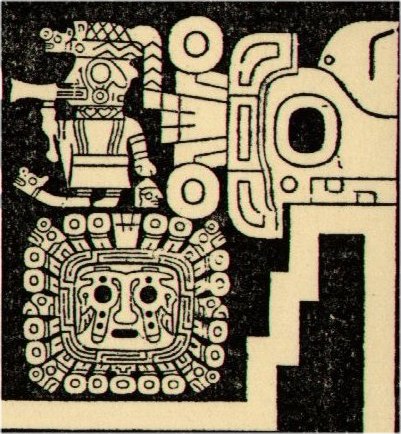

One solution for the 'female irrationality' in the duration of the period of the moon was earlier proposed by me to be adding months pairwise to reach natural numbers of days (59 for each such lunar double-month): In the beginning the methods of counting did not manage more than whole positive numbers. Therefore it was very inconvenient that the period of the phases of the Moon took more than 29 days but less than 30. Keeping order in the calendar for the Moon required some kind of trick. The trick established all over the ancient world (as I guess) was to count two periods, because with 59 days the problem was solved. The revolution of the phases of the Moon is very nearly 29 ½ days. And day no. 60 then became the first day of the new double-moon period. The Sumerians therefore had the same sign for 60 as for 1. Zero was not yet invented and there could be no misunderstanding if you knew what you were talking about (as people did at that time). Another solution was to disregard those nights when the moon was invisible: "... 'a day and a year' can be equated with the Thirteen Prison Locks that guarded Elphin, if each lock was a 28-day month and he was released on the extra day of the 365. The ancient common-law month in Britain, according to Blackstone's Commantaries (2, IX, 142) is 28 days long, unless otherwise stated, and a lunar month is still popularly so reckoned, although a true lunar month, or lunation, from new moon to new moon, is roughly 29½ days long, and though thirteen is supposed to be an unlucky number. The Pre-Christian calendar of thirteen four-week months, with one day over, was superseded by the Julian calendar (which had no weeks) based eventually on the year of twelve thirty-day Egyptian months with five days over. The author of the Book of Enoch in his treatise on astronomy and the calendar also reckoned a year to be 364 days, though he pronounced a curse on all who did not reckon a month to be 30 days long. Ancient calendar-makers seem to have interposed the day which had no month, and was therefore not counted as part of the year, between the first and last of their artificial 28-day months: so that the farmer's year lasted, from the calendar-maker's point of view, literally a year and a day." (The White Goddess) Curiously (and synchronously) I notice a paper slip in the book which I recently borrowed from the University Library at Lund (Barthel) demanding me to return the book within 364 days. I have never before seen that limit in practice. So we have two main calendar systems: The Egyptian solar one with 12 * 30 + 5 days and the Pre-Christian British month-as-luminary one with 13 * 28 + 1 days. The week is incommensurable with the Egyptian calendar but an important part of the month-as-luminary calendar. To these main calendar systems we now should add the Easter Island one (according to my reading of the beginning of Tahua) - a system with 3 extracalendrical days (The Sycomore Lady) between the years. I think we can see the same system in the Gateway of the Sun:

The feline cap on the strange chap has a tail connected to the crown of the 'crow'. This crown tells 3 twice: At the top middle of the crown we find 3 'fingers' (one of which is prolonged into the feline tail) and below the top part the 'cap' of the 'crow' is divided into three parts. The exact interpretation is not (yet) clear for me, but the two (double) circles certainly represent solar periods, presumably the old and the new year (with the double circles maybe representing half-years). The straight one of the three henua-like parts in the top of the cap of the crow may represent the season of solstice. If we allot each 'wife' of the sun to have 4 months, and reckon with 30 days for each such month, we will have 3 * 120 = 360 days in a year. We must have more days for each wife. However, 365 - 3 = 362, a number incommensurable with 3. Let us therefore once again have a look at those 3 X-glyphs in Tahua:

The 3rd one is divided into two parts and possibly straddles the gap between the years, it is a 'leap' glyph. Therefore we should count 365 - 2 = 363 = 3 * 121. From this I guess that each wife had 4 * 30 + 1 nights with the sun. Maybe the odd (final?) night had 'leap' character. The 'leap' glyph between the years (see above) first has a 'stop' sign in form of a closed leg and then a 'start' sign in form of an open arm. The explanation of Barthel about 'sitting like a tailor' (Schneidersitz) meaning 'submission' and 'slavery' cannot be true; the newborn year has open leg ends too, perhaps with a message similar to the sign of the unclosed arm. Though I prefer another explanation - at least provisionally - viz. that the 'unfinished' members amount to fractions, they are less than 1. The year is longer than 365 days and we get a more exact measure if we add 1 night every 4th year. The little chicken at right above has only one whole member, the right wing. Only 1 of the 4 possible members are drawn complete: He is just ¼ of a full day. If this interpretation is correct, we must draw the conclusion that there are 2¼ leap days in this Tahua calendar, 2 are belonging to the old year (1 for each half-year?) and ¼ belongs to the new year. Though a better understanding of what the writer had in mind probably is to say that there are 2 leap days between the years, and then we have 1 leap day each 4th year. That way we totally avoid fractional numbers. The leap day appearing every 4th year closes the cycle. |