|

TRANSLATIONS

Possibly the differences in the 1st periods of G and K are due to an ambition to point at similarities between the solar and lunar cycles:

In Ga2-27--29 three glyphs may allude to the necessary extracalendrical dark nights between 365 and 362. In Ga3-1 a new line begins with manu kake illustrating what was before and what will be - viz. at left a small-headed and small-winged bird (maybe meaning little 'water' - light - and little food) and at right the waxing season. If equinox (here spring equinox) implies ebb tide, and lots of edibles to pick from the flat beach, growth will come. When the Nile recedes the fertile earth will produce. Ka3-15 may allude (by reason of 15) to full moon (presumably a winter solstice event not only in Hawaii but also on Easter Island). Ka3-16 shows signs of 'spookiness', i.e. waning. The moon bird rules in Ka3-17 and 3 glyphs (Ka3-15--17) correspond to the 4 in G. There are 4 quarters in a year, but only 3 wives for the sun. Having created some order in the 1st half of period 1, we leave the 2nd half until later. Possibly a quick overview from midsummer onwards is the subject of the 2nd half. The tides create a doublet of the day, twice high tide and twice low tide, a fact which may have influenced the calendar builders. In Sharp as a Knife another important factor emerges: "The mythcreature behind the invitation is called dang tsin·gha quunigaay, 'your grandfather the big'. The qualifier quuna, big, has a special meaning here, as 'great' does in the English phrase 'great-grandfather'. Quuna is used alone to refer to a father-in-law, who is necessarily a senior male of the same moiety. In the Haida [matrilineal] kinship system, a person's own father is necessarily of the opposite moiety; so is one's mate. The father-in-law - the mate's father - is therefore always of the same side. Among grandfathers, one's mother's father is always of the opposite side, and one's father's father always of the same side. Tsin guuna is a male of the same moiety and the grandfather's generation, or indeed of any generation older than that. It means 'male ancestor, older than a father, of the same side'. The relationship between a younger male and such an ancestor is, therefore, potentially one of reincarnation." I find it difficult to see the patterns because I have no experience of matrilinearity. Yet, I can see how matrilinearity needs two moieties and how the male has to move from the moiety in which he was born to the opposite moiety where he finds his wife. His wife's father must also have moved in the same pattern. Therefore his father-in-law belongs to the same moiety as himself. All grownup married males in his wife's moiety - all the way back in time - must belong to the same moiety as himself. A person's own father must be from the opposite moiety too. He has been born in the opposite moiety and moved to mother's moiety at marriage. So he belongs to the same moiety as his wife. The same must be true for paternal grandfather - he also moved at marriage to grandmother's moiety (which is the same moiety as mother's). What is important, though, is that matrilinearity is strongly connected with a system with two equal parts, moieties. Just as the day has two equal parts of ebb-and-tide, so does matrilinearity and so should the year also be. Transposing a matrilinear society onto cosmos, we need two half-cycles for each cycle, fortnights for a month, half-years for a year etc. The reincarnation of grandfather - reappearing again when the same season (moiety) reappears - explains why Quetzalcoatl is his own ancestor: ... But what is surprising indeed was the manner of Quetzalcoatl's actual return. The priests and astrologers did not know in what cycle he was to reappear; however, the name of the year within the cycle had been predicted, of old, by Quetzalcoatl himself. Its sign was 'One Reed' (Ce Acatl), which, in the Mexican calendar, is a year that occurs only once in every cycle of fifty-two. But the year when Cortes arrived, with his company of fair-faced companions and his standard, the cross, was precisely the year 'One Reed'. The myth of the dead and resurrected god had circumnavigated the globe ... Father is the tanist, but grandfather is me:

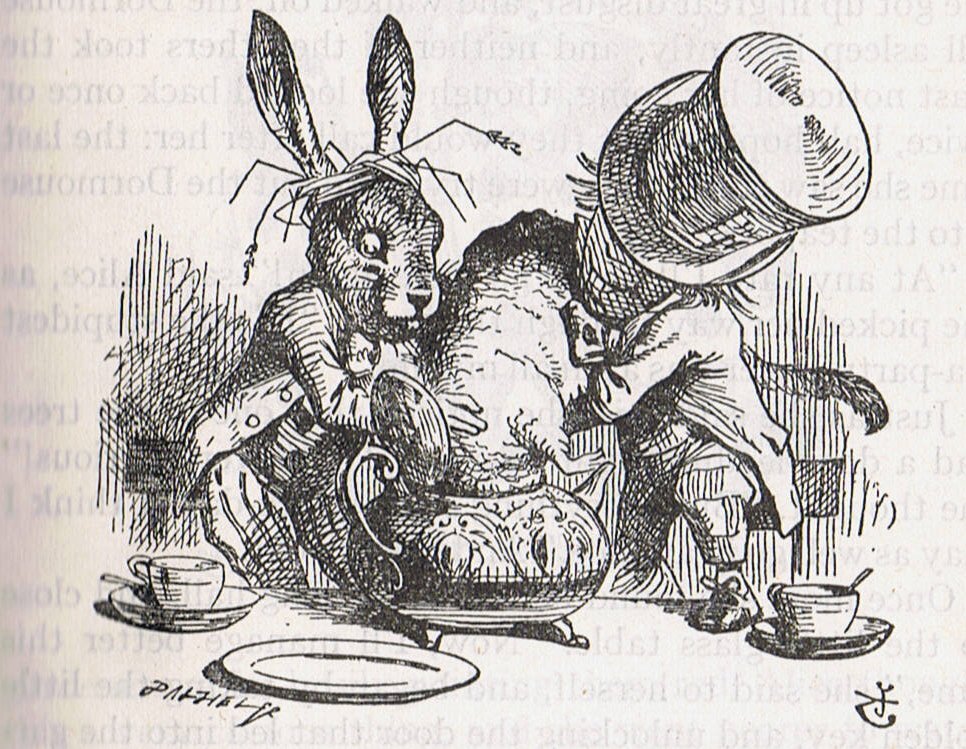

I remember how the Chesire Cat (from his place high up in the tree) informed Alice about the March Hare living in one direction (left) and the Mad Hatter in the other direction (right):

"... 'Tell us a story!' said the March Hare. 'Yes, please do!' pleaded Alice. 'And be quick about it', added the Hatter, 'or you'll be asleep again before it's done.' 'Once upon a time there were three little sisters', the Dormouse began in a great hurry: 'and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they lived at the bottom of a well — ' 'What did they live on?' said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking. 'They lived on treacle,' said the Dormouse, after thinking a minute or two. 'They couldn't have done that, you know', Alice gently remarked. 'They'd have been ill.' 'So they were', said the Dormouse; 'very ill'. Alice tried a little to fancy herself what such an extraordinary way of living would be like, but it puzzled her too much: so she went on : 'But why did they live at the bottom of a well?' 'Take some more tea', the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly. 'I've had nothing yet', Alice replied in an offended tone: 'so I can't take more'. 'You mean you can't take less', said the Hatter: 'it's very easy to take more than nothing'. 'Nobody asked your opinion', said Alice. 'Who's making personal remarks now?' the Hatter remarked triumphantly. Alice did not quite know what to say to this: so she helped herself to some tea and bread-and-butter, and then turned to the Dormouse, and repeated her question. 'Why did they live at the bottom of a well?' The Dormouse again took a minute or two to think about it, and then said 'It was a treacle-well.' 'There's no such thing!' Alice was beginning very angrily, but the Hatter and the March Hare went 'Sh! Sh!' and the Dormouse sulkily remarked 'If you ca'n't be civil, you'd better finish the story for yourself.' 'No, please go on!' Alice said very humbly. 'I wo'n't interrupt you again. I dare say there may be one.' 'One, indeed!' said the Dormouse indignantly. However, he consented to go on. 'And so these three little sisters - they were learning to draw, you know —' 'What did they draw?' said Alice, quite forgetting her promise. 'Treacle', said the Dormouse, without considering at all, this time. 'I wan't a clean cup', interrupted the Hatter: 'let's all move one place on.' He moved as he spoke, and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare moved into the Dormouse's place, and Alice rather unwillingly took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one who got any advantage from the change; and Alice was a good deal worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upsed the milk-jug into his plate ..." (Carroll)

Dormouse (Wikipedia). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||