|

TRANSLATIONS

I search through my Polynesian dictionary looking for 'step' and find a possibly useful piece of informaiton:

To stay inside, to avoid the sun, is like being in the night or in winter. Coming out is like early morning or spring. Flexing knees is to get the joints moving. ... During his descent the ancestor still possessed the quality of a water spirit, and his body, though preserving its human appearance, owing to its being that of a regenerated man, was equipped with four flexible limbs like serpents after the pattern of the arms of the Great Nummo. The ground was rapidly approaching. The ancestor was still standing, his arms in front of him and the hammer and anvil hanging across his limbs. The shock of his final impact on the earth when he came to the end of the rainbow, scattered in a cloud of dust the animals, vegetables and men disposed on the steps. When calm was restored, the smith was still on the roof, standing erect facing towards the north, his tools still in the same position. But in the shock of landing the hammer and the anvil had broken his arms and legs at the level of elbows and knees, which he did not have before. He thus acquired the joints proper to the new human form, which was to spread over the earth and to devote itself to toil ... If hiki belongs to spring, then wordplay would make us think of hoki and autumn:

Here next page in the glyph dictionary comes in naturally:

According to OgotemmÍli the joints were not there in the beginning, they arrived as a result of contact with Mother Earth. The function of the tuli bird is similar, to give a reason for why the joints appeared when they reached the new land. Fact is, joints are not there until the celestial being reaches the horizon. Fakataka swims and swims (Oti ai ia Kui ka kua kaukau ia Fakataka) in the ocean to the new island, while the divine smith comes from the sky. Water is both in the sky and in the ocean. On an island in Polynesia the horizon is not seen as lying straight out but seemingly located a bit upwards with the island as in a bowl. The word kaukau ('swims and swims'), though, implies a horizontal 'frame of reference'.

The newborn baby on the reef can move his hands and feet. His joints function. When he is able to stand by himself (mahaga) he will go forward. The 'island' ought to be formed like a rhomb:

I guess the rima and vae glyph types each represent two sides and a corner of this rhomb:

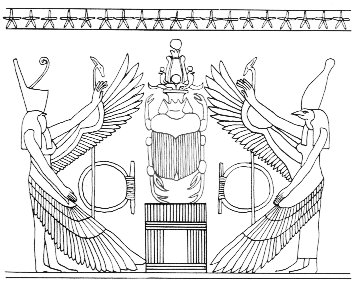

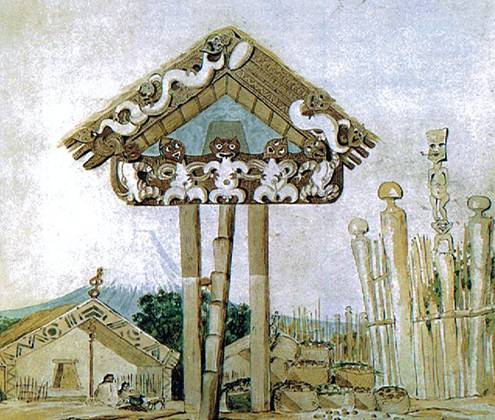

There are differences from the Egyptian concept, to be sure. To begin with, rima is a summer symbol (5 = hand → fingers → fire), while vae (as a consequence) should be a winter symbol. The elbow in rima is a corner, a cardinal point. Likewise the knee in vae refers to a cardinal point. If we define rima as the summer half of the 'earth', then the elbow corresponds to summer solstice (and the knee in vae to winter solstice). The Egyptian picture has protecting wings in north (left) and south (right), but leaves the path of the sun open from east (bottom) to west (top). On Easter Island the path of the sun also goes from east to west. The arm (rima) and leg (vae) ought to have the joints in north and south. Not until now have I noticed how the sun symbol at the top of the beetle is off center, more towards south. Egypt lies north of the equator and more sun is in the south. I have earlier hesitated to identify knee and elbow with the solstices - the cardinal points where the cours of the sun is quickly bent are the equinoxes. But there must be holes in east and west, therefore the joints presumably are the solstices. What evidence is there? Immediately we should remember the Taranaki store house:  The roof is like an arm with elbow at the top, which we earlier have coordinated with summer solstice. 3 'fingers' are at left and 4 at right (at the western horizon). Rima has its hand (including thumb) in the west: In the east there are only 3 'fingers' in the roof, likewise in the 'eating gesture'. There are 3 toes in a vae glyph. I suspect there is a connection between the 'eating gesture' and the lower part (below the knee) of the vae glyph.

During p.m. (as in Pa5-47) sun is growing, therefore a sign of eating. How do we know he is eating? Input it is, but not necessarily food. Leaving that question for the moment - there are 4 'rhomb sides' in rima + vae, but one is different form the other three, viz. the bottom part of vae. It is ending in a kind of hook. The feet in vae glyphs are not very naturalistic, which probably means they represent a necessary sign. I guess the feet are located in a phase when joints not yet (no longer) are present, they are what OgotemmÍli called 'flexible limbs like serpents'. The 'daylight' is blown out at autumn equinox and in darkness eyes function poorly. The straight henua 'limbs' are no longer present. The opposite must be there - seasons like the bodies of serpents. New year is born at winter solstice, the season of the serpents possibly arrives 3 quarters later. When sun is growing (feeding) the first thought ought to be that he is 'refilling' from vaiora a Tane, because at new moon she is doing that in order to realight. The concept of sunlight as a kind of healthy fluid as explained by OgotemmÍli: ... 'The life-force of the earth is water. God moulded the earth with water. Blood too he made out of water. Even in a stone there is this force, for there is moisture in everything. But if Nummo is water, it also produces copper. When the sky is overcast, the sun's rays may be seen materializing on the misty horizon. These rays, excreted by the spirits, are of copper and are light. They are water too, because they uphold the earth's moisture as it rises. The Pair excrete light, because they are also light ... ... 'The sun's rays,' he went on, 'are fire and the Nummo's excrement. It is the rays which give the sun its strength. It is the Nummo who gives life to this star, for the sun is in some sort a star.' It was difficult to get him to explain what he meant by this obscure statement. The Nazarene made more than one fruitless effort to understand this part of the cosmogony; he could not discover any chink or crack through which to apprehend its meaning. He was moreover confronted with identifications which no European, that is, no average rational European, could admit. He felt himself humiliated, though not disagreeably so, at finding that his informant regarded fire and water as complementary, and not as opposites. The rays of light and heat draw the water up, and also cause it to descend again in the form of rain. That is all to the good. The movement created by this coming and going is a good thing. By means of the rays the Nummo draws out, and gives back the life-force. This movement indeed makes life. The old man realized that he was now at a critical point. If the Nazarene did not understand this business of coming and going, he would not understand anything else. He wanted to say that what made life was not so much force as the movement of forces. He reverted to the idea of a universal shuttle service. 'The rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world' ... We should not hesitate to regard sunlight as a fluid. P.m. sun is drinking, not eating. After all, even stoneage man could deduce that boiling water evaporated upwards into the sky. Later rain came down to close the cycle. To quench a fire water is poured on top, steam results and the hot water in small particles rises upwards. This is a process which must in some way take place during winter, because so much hot 'fire' comes down during summer, with very little rain. The rain comes down in winter (generally seen), as if the celestial fire is being quenched. This explains why all the eternal old myths has the old man drinking water, making him 'go away'. Fire and water are complementary. The vae glyphs from knee down are possibly exhibiting the watery phase. It comes between new year and spring equinox, making it possible for sun to drink during p.m. It is, though, revitalizing him, not quenching him. Not sent to 'dull his reason'. How can I write this in the glyph dictionary? |