|

"Before the exploit

that is related here, the sea was greater and the land was less.

Only Hawaiki, the homeland, was dry for men. Maui, in spite

of his timid brothers' fears, pulled up the fish that bears his

name. The Maori say that the Fish of Maui is New Zealand.

HOW MAUI FISHED UP LAND

Maui, in the custom of

ancient times, had several different names. At the beginning he was

Maui potiki because he was the youngest child.

Then he had his

given name, Maui tikitiki a Taranga, and later he acquired

other names for different sides of his character.

According to what he

was up to he might be known as Maui nukarau, or

Maui-the-trickster; Maui atamai, Maui-the-quick-witted;

Maui mohio, Maui-the-knowing; Maui toa, Maui-the-brave;

and so on.

He was an expert at the

game of teka, or dart-throwing, and all the best patterns in

the string game of whai, or cat's cradles, were invented by

Maui.

He was also a great

kite-flier, and the story is told of a small boy of another name

(but it could only have been Maui) who once came half out of the

water and snatched the kite-string of a child on the land. He then

slipped back into the sea and continued flying it from under the

water until his mother was fetched, for she was the only one who

could control him and make him behave at that time.

It was Maui, moreover,

who invented the type of eel-trap that prevents the eel from

escaping once it is in. After he had slain Tuna roa he

constructed a hinaki that had a turned-back entrance with

spikes pointing inwards, so that the eels went in for the bait and

were trapped. Thus he always caught more eels than all his brothers

put together.

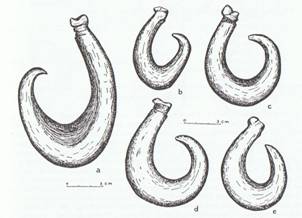

Again, it was Maui who

first put a barb on his spear for catching birds. The spears of his

brothers all had smooth points, but Maui secretly attached a barb to

his, and took it off again so that his brothers would not know. In

the same way also he secretly barbed his fish-hooks and always

caught more fish than they. This lead to some unpleasentness between

them.

The brothers grew tired

of all his tricks, and tired of seeing him haul up fish by the

kitful when they caught only a few. So they did their best to leave

him behind when they went out fishing. One day he assumed the form

of a tiwaiwaka, or fantail, the restless, friendly little

bird that flits round snapping flies. He flew on to their canoe as

they were leaving and perched on the prow.

But they saw through this at once and turned back, and refused to go

out with Maui on board. They said they had had enough of his

enchantments and there would only be trouble if he went with them.

This meant that he had to stay at home with his wives and children,

with nothing to do, and listen to his wives complaining about the

lack of fish to eat.

'Oh, stop it, you

women', he said one day when their grumbling had got on his nerves.

'What are you fussing about? Haven't I done all manner of things by

my enchantments? Do you think a simple thing like catching a few

fish is beyond me? I'll go out fishing, and I'll catch a fish

so big that you won't be able to eat it all before it goes bad.'

He felt better

when he had said this, and went off to a place where women were not

allowed, and sat down to make himself a fish-hook. It was an

enchanted one, and was pointed with a piece chipped off the jawbone

of his great ancestress, Muri ranga whenua.

When it was finished he

chanted the appropriate incantations over it, and tucked it under

his maro, the loin cloth which was all he wore.

Meanwhile, since

the weather looked settled, the brothers of Maui were tightening the

lashings of the top strakes of their canoe, to be ready for an

expedition the following day. So during the night Maui went down and

hid himself beneath the flooring slats. The brothers took provisions

and made an early start soon after daybreak, and they had paddled

some distance from the shore before Maui nukarau crept out of

his hiding place.

All four of them felt

like turning back at once, but Maui by his enchantments made the sea

stretch out between their canoe and the land, and by the time they

had turned the canoe round they saw that they were much further out

than they had thought.

'You might as well let

me stay now; I can do the bailing', said Maui, picking up the carved

wooden bailing scoop that was lying beside the bailing-place of the

canoe. The brothers exchanged glances and shrugged their shoulders.

There was not much point in objecting, so they resumed their

paddling, and when they reached the place where they usually fished,

one of them went to put the stone achor overboard.

'No, no, not yet!'

cried Maui. 'Better to go much further out.' Meekly, his brothers

paddled on again, all the way to their more distant fishing spot,

which they only used when there was no luck at the other one. They

were tired out with their paddling, and proposed that they should

anchor and put their lines overboard.

'Oh, the fish

here may be good enough for you,' said Maui, 'but we'd do much

better to go right out, to another place I know. If we go there, all

you have to do is put a line over and you'll get a bite. We'll only

be there a little while and the canoe will be full of fish.' Maui's

brothers were easy to persuade, so on they paddled once more, until

the land had sunk from sight behind them. Then at last Maui allowed

them to put he anchor out and bait their lines.

It was exactly as he

had said it would be. Their lines were hardly over the side before

they all caught fish. Twice only they had put their lines out when

the canoe was filled with fish. They had so many that it would have

been unsafe to catch more, for the canoe was now getting low in the

water. So they suggested going back.

'Wait on,' said Maui,

'I haven't tried my line yet.' 'Where did you get a hook?'

they asked. 'Oh, I have one of my own', said Maui. So the brothers

knew for certain now that there was going to be trouble, as they had

feared. They told him to hurry and throw his line over, and one of

them started bailing. Because of the weight of the fish they were

carrying, water was coming in at the sides. Maui produced his hook

from underneath his

maro, a magnificent, fishing hook it was, with a

shank made of paua shell that glistened in the sunlight. Its

point was made of the jawbone of his ancestress, and it was

ornamented at the top of the shank with hair pulled from the tail of

a dog. He snooded it to a line that was lying in the canoe.

Boastful Maui behaved

as if it were a very ordinary sort of fish-hook, and flashed it

carelessly. Then he asked his brothers for some bait. But they were

sulking, and had no wish to help him. They said he could not have

any of their bait. So Maui atamai doubled his fist and struck

his nose a blow, and smeared the hook with blood, and threw it

overboard.

'Be quiet now,' he told

his brothers. 'If you hear me talking to myself don't say a word, or

you will make my line break.' And as he paid out the line he intoned

this karakia, that calls on the north-east and south-east

winds:

Blow gently,

whakarua, / blow gently, mawake, / my line let it pull

straight, / my line let it pull strong.

My line it is pulled, /

it has caught, / it has come.

The land is gained, /

the land is in the hand, / the land long waited for, / the boasting

of Maui, / his great land / for which he went to sea, / his

boasting, it is caught.

A spell for the drawing

up of the world.

The brothers had no

idea what Maui was up to now, as he paid out his line. Down, down it

sank, and when it was at the bottom Maui lifted it slightly, and it

caught on something which at once pulled very hard.

Maui pulled

also, and hauled in a little of his line. The canoe heeled over, and

was shipping water fast. 'Let it go!' cried the frightened brothers,

but Maui answered with the words that are now a proverb: 'What Maui

has got in his hand he cannot throw away.'

'Let go?' he cried.

'What did I come for but to catch fish?' And he went on hauling in

his line, the canoe kept taking water, and his brothers kept bailing

frantically, but Maui would not let go.

Now Maui's hook

had caught in the barge-boards of the house of Tonganui, who lived

at the bottom of that part of the sea and whose name means Great

South; for it was as far to the south that the brothers had paddled

from their home. And Maui knew what it was that he had caught, and

while he hauled at his line he was chanting the spell that goes:

O Tonganui / why do you

hold so stubbornly there below?

The power of Muri's

jawbone is at work on you, / you are coming, / you are caught now, /

you are coming up, / appear, appear.

Shake yourself, /

grandson of Tangaroa the little.

The fish came near the

surface then, so that Maui's line was slack for a moment, and he

shouted to it not to get tangled.

But then the

fish plunged down again, all the way to the bottom. And Maui had to

strain, and haul away again. And at the height of all this

excitement his belt worked loose, and his maro fell off and

he had to kick it from his feet.

He had to do the rest with nothing

on.

The brothers of Maui

sat trembling in the middle of the canoe, fearing for their lives.

For now the water was frothing and heaving, and great hot bubbles

were coming up, and steam, and Maui was chanting the incantation

called Hiki, which makes heavy weights light.

At length there

appeared beside them the gable and thatched roof of the house of

Tonganui, and not only the house, but a huge piece of the land

attached to it. The brothers wailed, and beat their heads, as they

saw that Maui had fished up land, Te Ika a Maui, the fish of

Maui. And there were houses on it, and fires burning, and people

going about their daily tasks. Then Maui hitched his line round one

of the paddles laid under a pair of thwarts, and picked up his

maro, and put it on again.

'Now while I'm away,'

he said, 'show some common sense and don't be impatient. Don't eat

food until I come back, and whatever you do don't start cutting up

the fish until I have found a priest and made an offering to the

gods, and completed all the necessary rites. When I get back it will

be all right to cut him up, and we'll share him out equally then.

What we cannot take with us will keep until we come back for it.'

Maui then returned to

their village. But as soon as his back was turned his brothers did

the very things that he had told them not to. They began to eat

food, which was a sacrilege because no portion had yet been offered

to the gods. And they started to scale the fish and cut bits off it.

When they did this,

Maui had not yet reached the sacred place and the presence of the

gods. Had he done so, all the male and female deities would have

been appeased by the promise of portions of the fish, and Tangaroa

would have been content. As it was they were angry, and they caused

the fish of Maui to writhe and lash about like any other fish.

That is the reason why

this land, Aotearoa, is now so rough and mountainous and much

of it so unuseful to man. Had the brothers done as Maui told them it

would have lain smooth and flat, and example to the world of what

good land should be. But as soon as the sun rose above the horizon

the writhing fish of Maui became solid underfoot, and could not be

smoothed out again. This act of Maui's, that gave our people the

land on which we live, was an event next in greatness to the

separation of the Sky and Earth.

Afterwards these young

men returned to their home in

Hawaiki, the homeland. Their father,

Makea tutara, was waiting for them when they beached their

canoe, singing a chant that praised the mighty fishing feat of Maui.

He was delighted with Maui, and said to him in front of the brothers:

'Among all my children

only you, Maui tikitiki, are a great hero. You are the

renewal of the strength that I once had. But as for your elder

brothers here, they will never be famous like you. Stand up, Maui

tikitiki, and let your brothers look at you.'

This was all

that Makea tutara had to say to Maui on that occasion.

Afterwards Maui fetched his mother also, and brought her to

Hawaiki, and they all lived together there. Thus was dry land

fished up by Maui, which had lain beneath the sea ever since the

great rains that were sent by the Sky father and the god of winds.

The Maori people say that the north island of Aotearoa, which

certainly is shaped much like a fish, is Te Ika a Maui; and

according to some tribes the south island is the canoe from which he

caught it. And his hook is the cape at Heretaunga once known

as Te matau a Maui, Maui's Fishhook (Cape Kidnappers). In

some of the other islands which lie across the sea towards

Hawaiki, the people say that theirs is the land that Maui pulled

up from below." (Maori Myths) |