|

TRANSLATIONS

"Ravens, unlike geese, loons and many other birds, do not in fact have penises - a fact recorded and accounted for in several ways in Northwest Coast mythology." (Sharp as a Knife) The Raven must belong to the 2nd half of the year. He has no penis. The 1st half of the year, from midwinter to midsummer, is a season of growth - i.e. of procreation. By a strange coincidence a few days ago reading the morning paper at breakfast, a disturbing picture jumped at me:

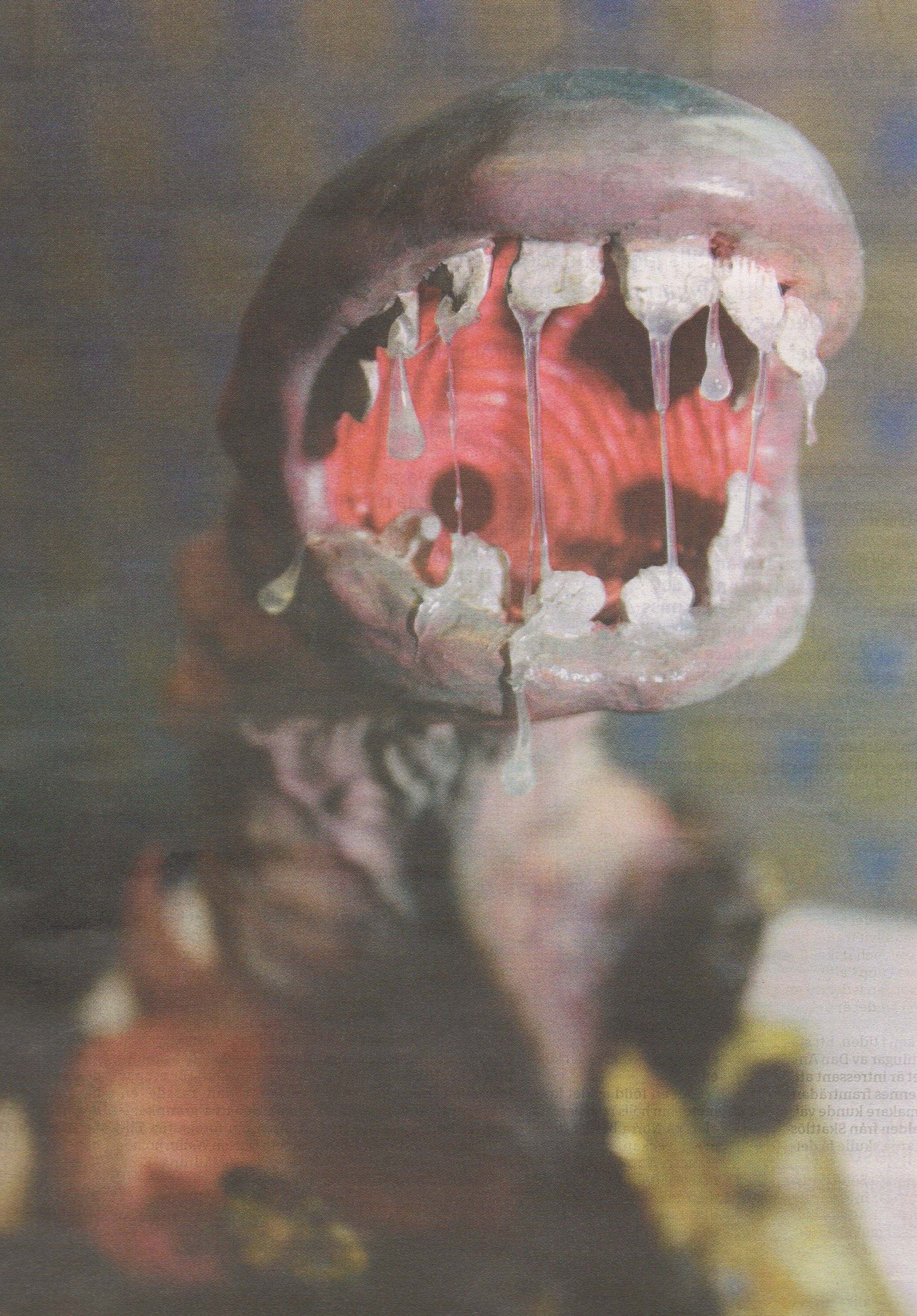

A local artist had made a little sculpture Kuken ska ha sitt ('My dick must have it.'), which had aroused protests when it was exhibited (in a place arranged by the community for children to play). The combination of erigated penis and voracious mouth is - I think - a true expression of the 'spring animal', the opposite of Raven. Max Magnus Norman, the artist, had been inspired by Frank Andersson, the world famous Swedish wrestler. During the Olympic Games 1984 in Los Angeles Frank had been asked by a reporter why he had vanished for a few days to Las Vegas,, and the answer was: 'Kuken ska ha sitt'. The information about Raven's missing penis is given in one of the footnotes to Chapter 13 'The Iridescent Silence of the Trickster', a strange name which - I think - was chosen with care. The subject is the Raven:

I can feel the story is singing the same tune as that of Max Magnus Norman. Although it is a rather long story, I believe it contains also other valuable clues for my quest. Let us therefore continue:

Of course, an old 'house' must give way at some point in time-space.

At the end of a cycle they must strip him. There must be sweeping, sweeping, and all old statues, pestles etc must be removed: ... Behold what was done when the years were bound - when was reached the time when they were to draw the new fire, when now its count was accomplished. First they put out fires everywhere in the country round. And the statues, hewn in either wood or stone, kept in each man's home and regarded as gods, were all cast into the water. Also (were) these (cast away) - the pestles and the (three) hearth stones (upon which the cooking pots rested); and everywhere there was much sweeping - there was sweeping very clear. Rubbish was thrown out; none lay in any of the houses ... But he will return (at dawn of course):

The tide has turned and now his 'face' is seen (last when they saw him going away they saw his back of course). Sea-foam (from which Aphrodite was born) marks the border between sea (winter) and land (summer).

The feast-rings of the pillar must be the marks needed for 'climbing', the sequence of steps towards the top.

The division of the year 'hat' into two parts is described. Marduk divided the night in two parts, but also the day must be divided in two parts in order to really create two separate cycles. Those 'villagers' who had 'wedged' themselves into the upper part of the 'hat' died. The pole without any visible marks has no survivors. Beyond 'a.m.' death lurks (and the Raven too).

In a footnote Bringhurst points out this is the only time in the poem when Raven is called Voicehandler.

In the evening, after all the actions of the day, it is time to sit down and tell stories. It is the time of the old people.

Bringhurst comments: "When he arrives at Qinggi's house, the Raven will eat nothing. The trickster is a creature who exaggerates everything he does, and here he is reborn as an aristocrat beyond the reach of ordinary needs. Hunger - his natural condition - is something the Raven must relearn. Ravens do indeed eat scabs as well as dung - though not as a rule their own. And it is evidently part of the trickster's job to reopen and maintain the world's wounds. But what exactly is it that the greedyguts teaches to the Raven? He [sic!] teaches him, it seems, to reduce himself to food - though hints of autocastration and masturbation also lurk in these instructions. After he has done as he is told - another atypical trick for the Raven - his hunger is restored. This is the main event in the first scene of the fourth movement. In the final scene, Qinggi - who has moved to the guest's position in the house - asks the Raven not to reduce but to enlarge himself to food. He asks him to feed others, by telling his own story. This yields the only moment in the poem when the Raven is ashamed." After the disorderly raw season of nature, the 1st half of the year, comes a more ordered sedentary season, a season of culture, and the feeding - therefore - must be cultural. The Voicehandler ought to speak. But he maybe still is hungry for the 'food' of 'a.m.'? Hungry people don't tell stories.

At his right means what is due. Little and swarthy is a description of evening time, I guess. Then follows 7 insulting speeches:

Bringhurst: "Raven rattles are used by all the indigenous peoples of the northern Northwest Coast and are known by cognate names in all the northern coastal languages: sheishóoxw in Tlingit, haseex in Nishga, sasoo in Tsimshian, siisaa in Haida. They are carved in two parts: belly and back. The Raven's head, wings and tail are part of the back. So is the humanoid passenger which the rattle usually carries. The belly (Haida qan, meaníng breast or ribcage) does not look like it could fly, and seldom has any discernibly avian elements. It is shaped as half an egg or a short canoe, and is usually engraved with the Raven's marine allotrope, Ttsam'aws, the Snag. Dance etiquette and conventional wisdom on the Nortwest Coast require that Raven rattles should be carried belly up most of the time, because they cannot fly away when held in that position." I remember the sistrum, the instrument of darkness:

The 7 insults to the gods are the disturbances caused at cardinal points. If they die on the spot, it meands a cardinal point. 364 / 7 = 52. The first insult was the 10 joints (rings) long 'bull kelp stalk'. The bull is a symbol of raw nature. The 2nd was the rainbow arching towards its own back, a colourful cycle. The rainbow appears when sun light splits the murky winter apart. The 3rd presents twin gods, the gull and the cormorant. Bringhurst: "The cormorant mentioned here is sghiitghun, 'red gullet'. This is the double-crested cormorant, P. auritus, which visits the Island in the fall."

(Double-crested cormorant, Phalacrocorax auritus. The crests are normally not visible. Wikipedia) Gull represents the 1st 'raw nature' year, while the cormorant represents fall. What Harlequin Duck and Steller's Jay represent I don't know for the moment:

(Wikipedia)

The edge of the village means the end of the year. At the end of a cycle a net of some kind must catch the sun. Bringhurst informs that 'Plain Old Marten and the other one' refers to Taadlat Ghadala and Kkuxu Ginagits, or Swallow and Marten.

(Wikipedia) Why does not Bringhurst anywhere in his book explain the correlations between seasons and mythic creatures? As a poet he must know, and the knowledge surely cannot be forbidden. Maybe it is so trivial as not worthy of mentioning? Those who understand will understand, those who don't will never understand. |