|

TRANSLATIONS

Confirmation is seen in Pa5-41 that light arrives from the left (east) at daybreak (Pa5-40), because the shadows (dark part of henua) is at right:

We - who live north of the equator - prefer to mark our maps with north at the top and therefore it is not surprising to find the Easter Island viewers facing south. The little 'sun' symbol normally found at right in hau tea (GD41) is not the sun but the moon. Moon rises in the west and sets in the east, the opposite path compared to the sun. Tea means white and that is the colour of the moon (while the sun is red or yellow). Yet hau tea is used also - it seems - in describing the light from the sun. This we should be able to read not only in Tahua but also in the calendars for the year (to mark spring) in e.g. Ga4-5 (supposedly spring equinox):

However, the hand gesture probably means 'end', and therefore what is ending seems to be the 'light from the moon' (we see no opening of the 'roof' at left in hau tea, and no 'spreading out' sign either). That the hand gesture probably means 'end' is a conclusion which we have reached earlier by way of Aa1-48 (end of night) and Aa1-86--90 (end of year):

The hand in Aa1-48 unquestionably, though, is different - by way of some additional sign - from the hands in Ga4-5 and Aa1-86. The white (tea) light from the moon should be contrasted with the red (mea) light from the sun. Metoro's tapa mea (red cloth) for GD55 probably is correct:

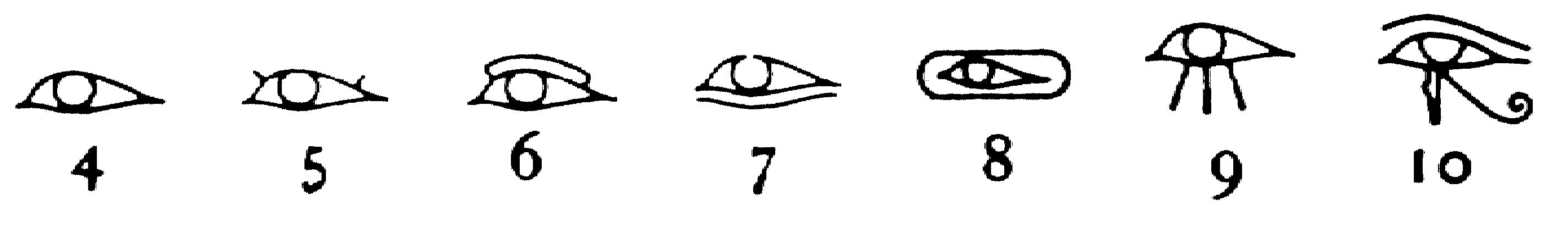

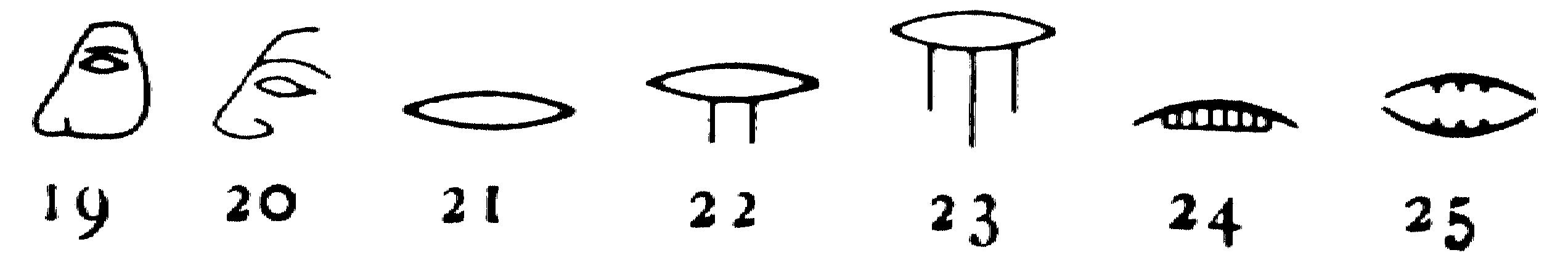

The term 'red cloth' for the daylight should, though, first of all be contrasted with the absence of sunlight during the night, the 'black cloth' (symbolizing death - while the daylight symbolizes life). There is an Egyptian hieroglyph which resembles GD55, no. 23 in the presentation below:

If we turn GD55 around we can see the similarities clearly:

In no. 23 the 3 vertical lines with the middle one longest, correspond to the twice 3 outspreading lines with the middle one shortest in GD55. I do not know what no. 23 means, but presumably we see an eye with vision. No. 9 is similar, though here the eye is written more naturalistic. Maybe no. 3 depicts the sun rays, while no. 23 was used to convey the concept of vision. No. 23 perhaps illustrates the concept of white light, meaning that the lense is the moon? The vertical rays do not spread out and in GD55 the middle vertical line is shorter, not longer. Therefore, my guess is that no. 9 is mea, while no. 23 is tea (and 24 may be absence of light - like in an overturned boat). The eye has the shape of a canoe. Though nos. 24 and 25 may be pictures of mouths (teeth visible in no. 24). GD55 rotated this way has the little gap at left - in the east. If the picture show us the daily orbit of the sun, 'birth' and 'death' is at dawn. Listing all GD55 glyphs in Tahua we have:

Concentrating on the non-complex glyphs we have:

Number 26 presumably alludes to the 26 * 14 = 364 days in a year. 8 + 8 = 16 agrees with the number of lines of Tahua, 8 on each side. If we add the 10 during the daytime to the other 8 on side a, we have 18 non-complex GD55 on side a. Maybe that number alludes to 18 20-day periods for the solar year?

We should remember Ogotemmêli's words: '... Ogotemmêli had his own ideas about calculation. The Dogon in fact did use the decimal system, because from the beginning they had counted on their fingers, but the basis of their reckoning had been the number eight and this number recurred in what they called in French la centaine, which for them meant eighty. Eighty was the limit of reckoning, after which a new series began. Nowadays there could be ten such series, so that the European 1,000 corresponded to the Dogon 800. But Ogotemmêli believed that in the beginning men counted by eights - the number of cowries on each hand, that they had used their ten fingers to arrive at eighty, but that the number eight appeared again in order to produce 640 (8 x 10 x 8). 'Six hundred and forty', he said, 'is the end of the reckoning.' According to him, 640 covenant-stones had been thrown up by the seventh Nummo to make the outline in the grave of Lébé ...'

Why are not the hands and feet included? We ought to have had circles with numbers 10-13 for them in the picture above, I think. Twice 64 marks on the non-reversed GD55 on Tahua means two wholes. 59 + 58 + 58 = 175 and the difference between 64 and 58 is 6 (the solar number), while the difference between 64 and 59 is 5. 5 + 6 + 6 = 17, what does that number mean? There are 17 marks on the reversed GD55 in the daylight calendar too. 175 - 3 * 64 = 17. Whatever 17 may mean, we presumably should think of three wholes (with the daylight calendar being one of them). There seems to be double-talk here. 59 presuambly alludes to the double-moon period needed to reach a whole number. 58 therefore ought to refer to the sun. But if that is so, then side b of Tahua should tell about the adventures of the sun in the underworld (not about the cycle of the moon). Those 10 GD55 in the daytime calendar have 59 marks on them and that should refer to the moon. But why? Wouldn't it have been better, instead, to have 3 * 58 = 176 (with 176 - 3 * 64 = 16)? Maybe the answer is that 59 - 64 = 5 and 5 * 12 = 60. Perhaps there was a period with length 20 days. 4 * 5 = 20 and we could then interpret the variant of GD53 with triple rhombs (e.g. Aa1-78) as 3 * 20:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||