|

TRANSLATIONS

Now I feel prepared to go on with henua in the glyph dictionary. First page:

|

A few preliminary

remarks and imaginations:

1. Perhaps this type of glyph

is an image of

a wooden staff (kouhau). Such were used in different circumstances:

measuring, memory aids (cutting marks in the wood), sign of power

etc.

"He [Eric Thompson]

established that one sign, very common in the [Mayan] codices where it

appears affixed to main signs, can be read as 'te' or 'che',

'tree' or 'wood', and as a numerical classifier in counts of periods

of time, such as years, months, or days.

In Yucatec, you cannot for

instance say 'ox haab' for 'three years', but must say 'ox-te

haab', 'three-te years'. In modern dictionaries 'te'

also means 'tree', and this other meaning for the sign was confirmed

when Thompson found it in compounds accompanying pictures of trees

in the Dresden Codex." (Coe)

The possible connection between a measuring staff and a numercial

classifier for time periods made me early on in these studies

conclude it was the origin of the glyph

type henua. At tagata ('a fully grown season') I have therefore suggested that henua glyphs

(here below Eb3-3 and Eb5-6) were used in the meaning 'season', 'period', etc:

|

Although in G the location of summer in the text now is definitely determined, in E we have no such security. The suggested readings (of 'winter' respectively 'summer') could be wrong, but I will let them remain until disproven.

2. My

confidence lead me to further speculations:

'Winter' has

the short ends of the staff

indented

meaning less sun. The

man in 'winter' has a 'barren' Y-shaped hand and his elbow ornament in not

complete (at spring equinox there will still remain three months

to summer solstice). The

man in 'summer' has a 'growing' arm and no incomplete elbow

ornament ...

When

the staff has

hatchmarks across it, e.g. (Ab2-38):

it probably means a time

when sun is below the horizon, and the short ends of henua are,

significantly, then never drawn indented (as in

'winter', cfr above)

...

There is a double meaning in

henua, not only a period of time but also

a connection with

light. Henua without hatchmarks means a period of light,

henua with hatchmarks a period of darkness. There are no henua in

the Mamari calendar for the

moon, because the 'land of the moon' is the night. Instead, for a

period of night the marama glyph type was used. Calendars

involving sun and light use henua (or tapa

mea.as in the 'calendar' for the daytime). In the

Japanese language yellow is 'kiiro' (ki-iro =

tree-colour) and 'tree' is written with the Chinese character

showing a tree:

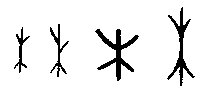

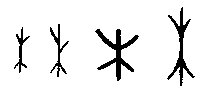

The four examples at right are early variants (ref. Lindqvist). The

wood of a tree is yellow and the sun is yellow, therefore the stem

of a tree could be used as a symbol for the sun and - more precisely

used - as the path of

the sun.

On the other hand, the Chinese had also another character derived

from the picture of a tree, and this they used for the colour red (aka

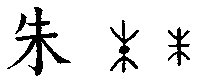

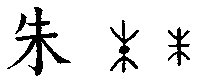

in Japanese):

In the early examples of this character the stem of the tree is

marked with a dot (middle) or a horizontal line (right). The Chinese used the stem of certain trees to make

red colour pigment. Red or yellow - both colours are like

the sun. On Easter Island they preferred to use the hard reddish

wood from toromiro for all kinds of wood work, like houses,

canoes and sculptures. This kind of wood was in ancient times

sacred. To illustrate the path of the sun the stem of a tree

was used. That is the origin of the picture behind the henua

glyph type ...

|

Numerical classifiers may be in the background, being the reason why there are different time period endings:

|

3. Gradually doubts were accumulating. A major obstacle was

Metoro. If he saw

a piece of land

in this glyph type then surely it could not at the same time be a picture of a tree stem

(or measuring staff). My esteem of Metoro has steadily

grown and he certainly knew what he was talking about.

The Mayan te glyph - I have learnt - has no resemblance at

all with henua:

A sun symbol is at left (like an eye with a pupil in the middle), while at right - I guess - is a picture of the sky from

which what looks like 'rabbits teeth' are shining down, delivering their rays

(illustrated like the 'feathers' in rongorongo) to

earth below. This was a wooden club used for aggression, not a

peaceful agricultural tool. (The picture is from Kelley, the words

and imaginations are mine.)

Using a Mayan structure for sun

'residences' over the year the parallel to henua instead

should be the time of maximum growth before the arrival of midsummer:

Here the so-called 'Rain God' (Kelley's term for the sun) is seen walking on land - footprints are

used for describing the 'residence', his station in time, viz.

'land'.

Footprints can only be created on the surface of earth, neither sea

nor sky can do. The outline of

the rectangular form at bottom may be the origin of the henua

glyph type, I reasoned.

But I did not assume any contact between the Polynesian and the

Mayan peoples - a piece of land will be drawn as a rectangular form

irrespective of where on earth we look.

|

He has a double head-piece. Perhaps different versions of the head-piece could give information:

|