|

TRANSLATIONS

Women are giving

birth and men

are killing,

strange then

that vai

means birth

(light) and

hua poporo

death (shadow).

The sweet

rainwater (vai)

from heaven is

coming from

above, the male

(vertical)

domain, while

the salt water

in the ocean (tai)

is lower down

than the pools

of rain water in the land

raised up by

Maui.

Life originates

in the sea and

the tidal beach

is henua,

I imagine -

he-nua (-

hine), the

old woman.

The land side (uta)

needs water from

the sky, while

the tidal zone

is

self-sufficient.

Heyerdahl

pointed to the

Northwest Coast

indians as the

probable origin

of those who

emigrated to

Hawaii:

|

...

The

great

'wandering

chief'

who

is

said

to

have

discovered

the

Hawaiian

islands

is

alluded

to

as

Hawaii-loa,

or 'Hawaii-the-great',

(but

his

name

is

also

repeatedly

given

as

Ke

Kowa-o-Hawaii,

or

'The

Straits

of

Hawaii'.

(Fornander

1878,

Vol.

I,

p.

23,

25.)

The

island

Hawaii

was

named

after

this

mythical

wanderer,

and

hence

the

name

must

be a

very

ancient

one

brought

to

Hawaii

by

its

early

settlers.

Fornander

himself

was

sufficiently

familiar

with

the

Polynesian

predilection

for

allegories

and

symbolic

names

to

realize

that

'the

Straits

of

Hawaii'

was

merely

a

poetical

device,

a

descriptive

mythical

name

personified

in

the

local

discoverer,

and

he

proceeded

to

trace

its

possible

origin.

He

and

others

have

shown

that

Hawaii,

alias

Hawaiki,

is a

composite

name,

consisting

of a

root

with

the

suffix

ii,

alias

iki.

Iki

is

the

original

form,

and

ii

the

result

of a

later

dropping

of

the

letter

k.

Philologists

have

suggested

two

possible

meanings

for

this

suffix;

on

one

hand

'small'

or

'little';

on

the

other

'furious'

or

'raging'

as

referring

to a

volcano

in

eruption.

The

improbability

of

the

first

of

these

meanings

is

apparent

from

the

old

Polynesian

use

of

words

like

Hawaii-loa

and

Hawaii-nui,

which

would

produce

the

senseless

suffix

'Little-Great'.

And,

as

shown

by

Fornander

(Ibid.,

p.

6),

a

Marquesan

tradition

shows

plainly

that

ii

refers

to a

volcano:

'...

in a

chant

of

that

people,

referring

to

the

wanderings

of

their

forefathers,

and

giving

a

description

of

that

special

Hawaii

on

which

they

once

dwelt,

it

is

mentioned

as

Tai

mamao,

uta

oa

tu

te

Ii

- a

distant

sea

(or

far

off

region),

away

inland

stands

the

volcano

(the

furious,

the

raging).'

According

to

Henry

(1928,

p.

115),

also

Tahitian

folklore

often

spoke

of

Hawaii

Island

as

Havai'i-a,

or

'Burning

Havai'i',

due

to

its

volcano

which

was

formerly

always

brightly

burning.

Thereupon

Fornander

and

others

with

him

removed

the

epithet

ii

or

iki,

and

looked

to

the

west

for

a

place-name

equivalent

to

Hawa

(of

Hawaii),

Sava

(of

Savaii),

or

Hapa

(of

Hapaii).

Suspicion

naturally

fell

on

Java,

and

the

name

of

this

island

was

by

many

considered

the

clue

to

the

'whence'

of

the

Maori-Polynesian

ancestors.

After

jumping

a

good

6,000

miles

from

Hawii

to

Java,

he

then

took

a

further

leap

of

5,000

miles

back

to

Zaba,

the

early

seat

of

Cushite

empire

in

Arabia,

as

the

ancestral

starting

point.

However,

finding

nowhere

any

'Strait'

with

a

name

equivalent

to

Hawa

or

Hawaii,

Fornander

(p.

25)

simply

suggests

that

the

allegoric

reference

to

the

Hawaiian

discoverer

as

'the

Straits

of

Hawaii'

must

refer

to

the

Hawaiian

memory

of a

now

lost

name

for

the

Straits

of

Sunda

between

Java

and

Sumatra.

Here

the

question

was

left.

Taking

up

Fornander's

original

clue,

the

present

author

suspected

that

Hawai

(or

Savai,

Hapai)

might

have

been

the

old

root

from

which

the

name

sprang,

rather

than

Hawa.

As

stated

earlier,

Whatonga's

legendary

canoe

in

Hawaiki

was

named

Te

Hawai,

not

Te

Hawa

nor

Te

Hawaiki;

and

in

Hawaii

ancient

place-names

like

Kaha-hawai,

Puna-hawai,

etc.

are

found.

Even

more

suggestive

is

the

fact

that,

as

stated,

the

epithet

ii

or

iki

refers

to a

raging,

active

volcano,

of

which

there

are

none

in

Polynesia

outside

the

Hawaiian

and

Samoan

groups

and

New

Zealand.

There

are

two

in

Hawaii

in

the

Hawaiian

Group,

and

another

in

Savaii,

but

there

is

none

in

Hapai

in

the

Tonga

Islands.

Therefore,

Hawaii

and

Savaii,

but

not

Hapai,

have

been

given

the

suffix

ii,

denoting

a

volcano.

Yet,

even

without

the

ii,

this

Tonga

island

is

known

as

Hapai

and

not

as

Hapa,

quite

in

keeping

with

the

name

of

Whatonga's

canoe

Te

Hawai

from

Hawaiki.

The

reduction

of a

consonant,

changing

Hawaiki

to

Hawai'i

and

Hapaiki

to

Hapai'i,

is a

well

known

process

in

Polynesian

speech,

but

no

Polynesian

dialect

would

abbreviate

Hapai'i

to

Hapai.

On

the

other

hand,

Hapai

may

very

well

be

the

root

of

Hapai-iki,

and

the

canoe

Te

Hawai

may

be

the

root

of

Te

Hawai-iki.

Recalling

at

the

same

time

the

marked

softening

tendency

throughout

Polynesian

speech,

the

p

in

Hapai

is

obviously

an

older

form

than

w

in

Hawai.

On

these

premises

I

resumed

the

search

outside

Polynesia

for

Hapai,

or

even

for

the

more

guttural

Hakai.

In a

general

world

atlas

(Philip

1934,

p.

191)

I

checked

up

on

the

principal

straits

between

the

islands

in

the

Northwest

American

Archipelago,

and,

between

the

Hunter

and

Calvert

Islands,

right

in

the

midst

of

the

Kwakiutl

territory,

was

the

Hakai

Strait.

If

Hakai

had

been,

for

instance,

in

Europe

or

Argentina,

or

if

it

had

been

a

mountain-ridge

or

an

island,

instead

of a

principal

strait

among

the

Northwest

Indians

of

the

particular

Kwakiutl

tribe,

then

it

might

well

have

been

attributed

to

simple

coincidence.

But

if

we

are

actually

looking

for

a

certain

strait

with

a

certain

name,

located

between

the

limited

number

of

islands

in

Kwakiutl

territory,

and

we

actually

find

it

there,

that

it

be

coincidence

can

no

longer

be

considered

... |

|

...

There

are

still

traces

to-day

of

some

ancient

habitation

on

the

coast

of

the

Hakai

Strait,

although

in

historic

times

it

has

only

served

the

surrounding

tribes

as a

dependable

fishing-ground

and

source

of

food.

It

may

be

worth

while

to

note

that

in

the

dialect

of

the

Marquesan

islanders

hakai

means

'to

feed'.

In

Easter

Island

the

word

reappears

as

hagai,

which

means

'to

feed,

to

nourish';

and

at

Mangareva

as

agai,

'to

give

food

to'.

In

the

Marquesas

kai

and

kai-kai

means

to

'eat';

and

on

the

Northwest

Coast

kaik

(Tsimsyan)

and

ka-aia

(Tlingit)

means

'belly';

and

ka-ta

(Haida)

means

to

'eat'.

We

have

ample

reason

to

suspect

that

the

particular

Hawai

or

Hapai

Strait

alluded

to

in

the

symbolic

name

of

the

Hawaiian

discoverer

is

the

Hakai

Strait,

the

direct

geographical

link

between

the

tribes

driven

away

from

prehistoric

Bella

Coola

and

those

driven

ashore

in

prehistoric

Hawaii.

It

is

well

worth

noticing

that

in

historic

times

it

is

among

the

surrounding

Kwakiutl

and

not

among

the

Bella

Coola

intruders,

that

we

find

the

main

bulk

of

Maori-Polynesian

analogies;

also

that

the

Kwakiutl,

according

to

Drucker's

survey,

represent

the

purest

-

and

together

with

the

Nootka

perhaps

also

the

oldest

-

aboriginal

coast-dwellers

in

the

present

Northwest

Indian

habitat

... |

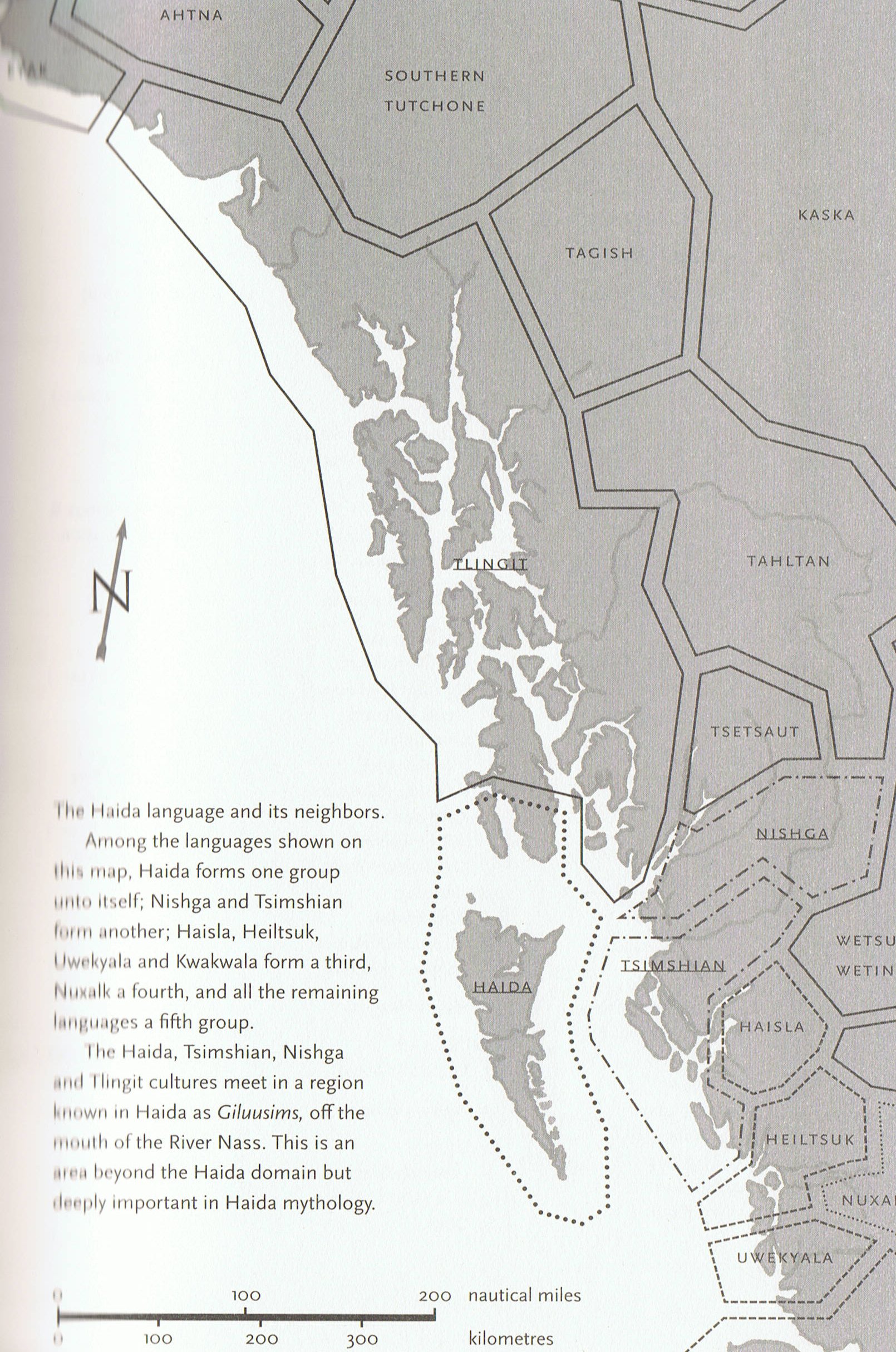

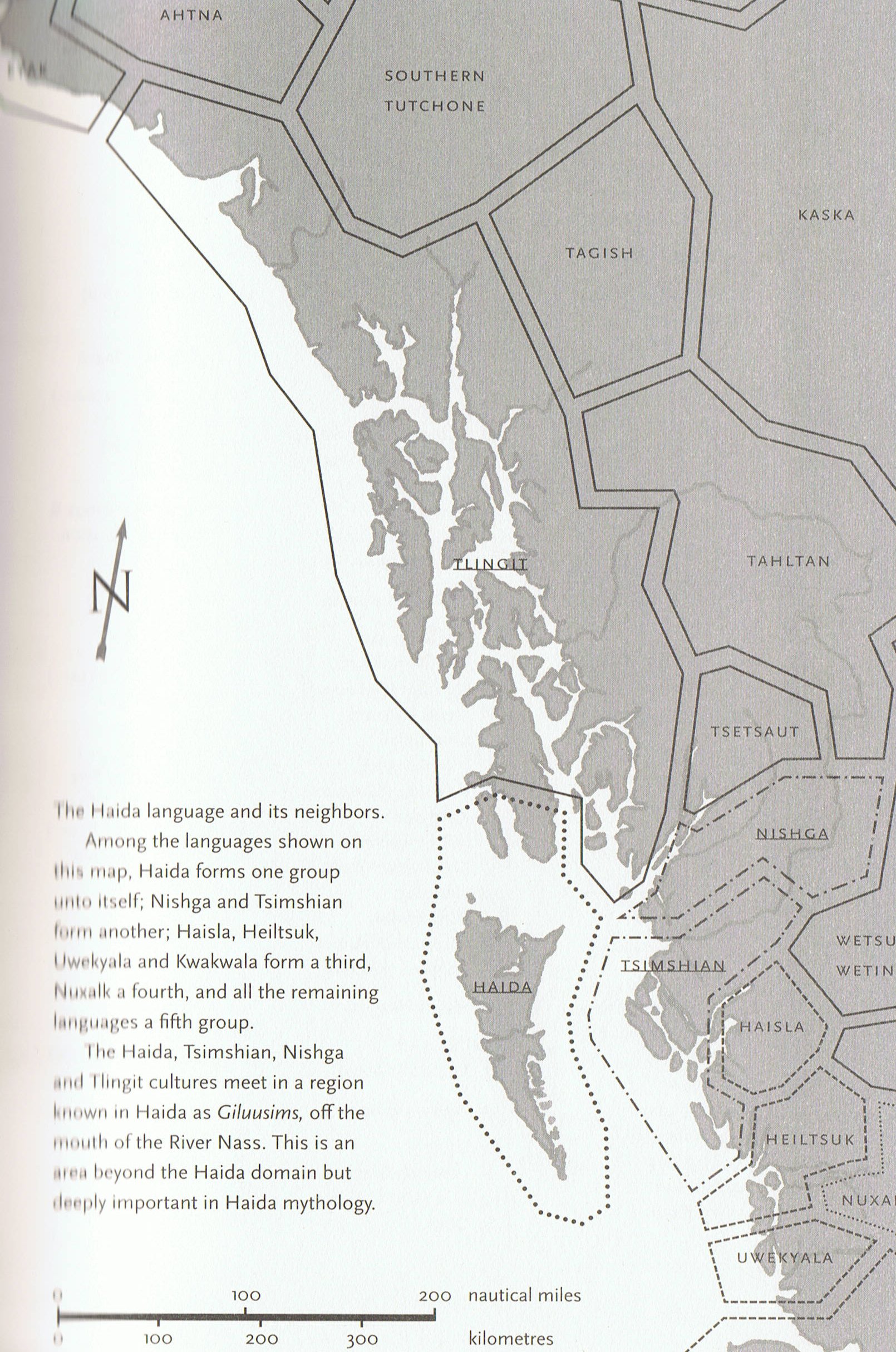

I borrowed A

Story as Sharp

as a Knife

from the library

in order to see

if there are

any connections

among the ideas

of the Haida

indians and what

slowly seems to

be

emerging from

the

rongorongo

texts.

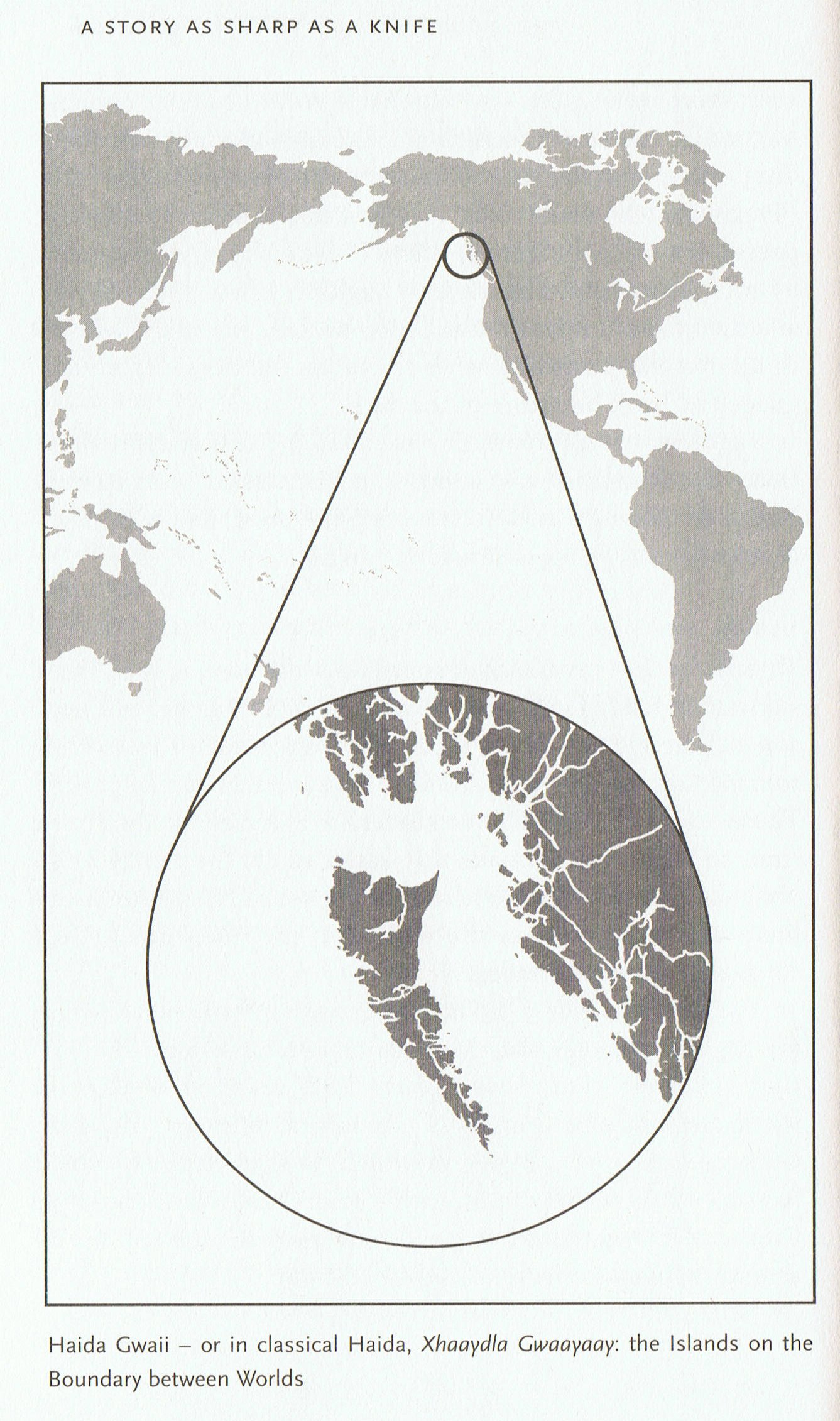

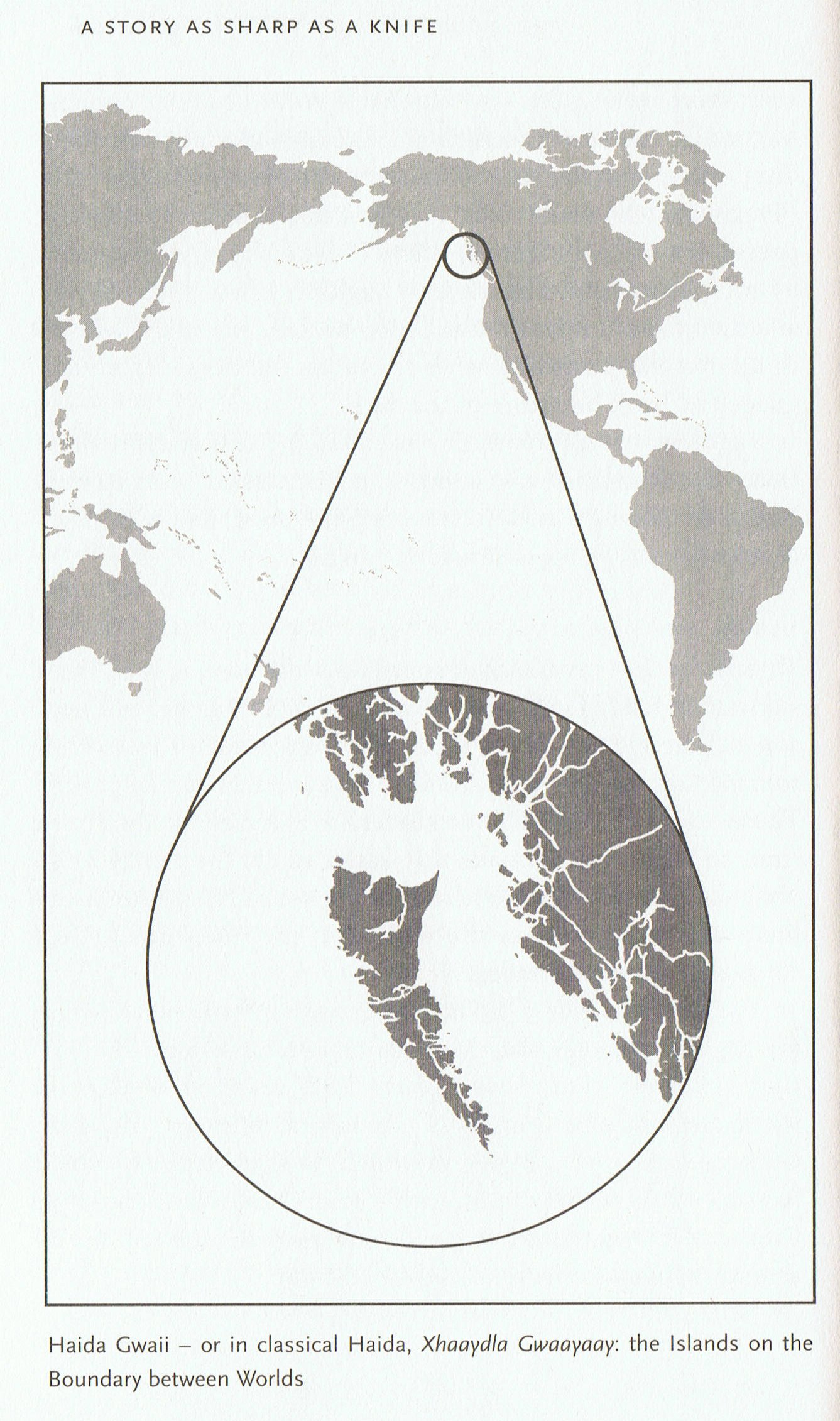

The indigenous

name for Queen

Charlotte Island

- where the

Haida indians

live - is

Haida Gwaii,

a name sounding

suspiciously

similar to

Hawaii:

Hawaii -

Ha(-idag)waii

Yet, the Haida

language is

totally

different from

Polynesian,

example:

|

Aanishaw

tangagyanggang,

wansuuga. |

Hereabouts

was

all

saltwater,

they

say. |

|

Li

xitgwaangas,

Xhuuya

aa. |

He

was

flying

all

around,

the

Raven

was, |

|

Tigu

qqawgashlingaay

gi

lla

quaangas. |

looking

for

land

that

he

could

stand

on. |

|

Qawdihaw

gwaay

ghutgwa

nang

qaadla

qqaayghudyas, |

After

a

time,

at

the

toe

of

the

Islands,

there

was

one

rock

awash. |

|

llagu

qqawghaayghan

llagha

lla

xiidas. |

He

flew

there

to

sit. |

| |

|

Aa

ttl

sghaana

quiidas

yasgagas

ghiinuusis

gangaang |

Like

sea-cucumbers,

gods

lay

across

it, |

|

llagu

gutgwii

xhihldagahldiyaagas. |

putting

their

mouths

against

it

side

by

side. |

|

Ga

sghaanagwaay

ghaaxas

lla

ttista

qqaa

sqqagilaangas, |

The

newborn

gods

were

sleeping,

out

along

the

reef, |

|

ttl

gwiixhang

xhahlgwii

at

wagwii

aa. |

heads

and

tails

in

all

directions. |

|

Ghaadagas

gyaanhaw

ising

ghaalgagang,

wansuuga

... |

It

was

light

then,

and

it

turned

to

night,

they

say

... |

This is the

beginning of

the Poem

of the

Elders,

as recounted

by Skaay.

Searching

for words

which may be

related to

Polynesian

ones, I find

only one

such:

wansuuga

(they say)

which rings

similar to

vanaga.

|

Vánaga

To

speak,

to

talk,

to

pronounce;

conversation,

talk,

word,

language;

he

vânaga

i te

vânaga

rapanui,

to

speak

Rapanui;

vânaga

reoreo,

lies,

lying

words,

falsehoods.

Vanavanaga,

to

talk

at

length;

useless

talk.

Vanaga.

To

speak,

to

say,

to

chat,

to

discourse,

to

address,

to

recount,

to

reply,

to

divulge,

to

spread

a

rumor;

argument,

conversation,

formula,

harangue,

idiom,

locution,

verb,

word,

recital,

response,

speech;

vanaga

roroa,

chatterbox,

babbler;

rava

vanaga,

candid,

babbler;

tae

vanaga,

discreet;

tai

vanaga,

ripple;

vanagarua

(vanaga

-

rua

1),

echo.

P

Pau.:

vanaga,

to

warn

by

advice.

Mgv.:

vanaga,

orator,

noise,

hubbub,

tumult.

Mq.:

vanaa,

orator,

discourse,

counsel,

advice.

Churchill. |

Although

Heyerdahl

searched for

a strait

(because of

the name of

'the

wandering

chief'

Ke

Kowa-o-Hawaii,

The

Straits of

Hawaii), I

think it

would be

more true to

search for

an island,

and Queen

Charlotte

Island is a

natural and

good

candidate.

Haida

Gwaii

means (among

other things

I suppose)

'the Islands

on the

Boundary

between

Worlds' (Xhaaydla

Gwaayaay).

The worlds could

be America

and

Polynesia,

but other

meanings are

equally

possible,

for instance

land and

sea.

Rocks

awash in salt water

was

nourishing

sea-cucumbers,

the newborn

godlings.

This was

before light

and

darkness, in

the misty

beginnings.

"It is a

peculiarity

- or a

pathology,

perhaps - of

centrally

administered

and

urbanized

societies to

want to see

the world,

including

the gods, in

strictly

human terms,

or to see it

still more

narrowly, in

terms of a

single

language,

faith and

culture.

Industrial

societies

habitually

go further,

dropping the

gods

overboard

and

classifying

all nonhuman

beings - and

often other

human beings

too - as

'natural

resources'

waiting to

be used.

In classical

Haida

literature

and art,

humans never

exercise

such

dominance.

The ritual

combat of

man against

man, man

against

nature, and

man against

himself

- reputedly

the

elemental

themes of

modern

European

literature -

are never

more than

secondary

subject

matter here.

Classical

Haida poets

spend much

more time

exploring

the

connections

between

humans and

nonhumans -

sea mammals,

land

mammals,

fish, birds,

and the

sghaana

qiidas,

'those who

are born as

spirit

powers', the

gods.

Skaay and

Ghandl speak

of three

distinct

realms -

forest, sea

and sky -

each with

its native

populations.

None of

these,

however, is

the human

realm.

Humans are

only at home

on the

xhaaydla,

the boundary

or

intertidal

zone, at the

conjunction

of all

three. A few

strokes of

the paddle

or a few

steps into

the bush are

enough to

leave the

human world

behind."

(Sharp as a

Knife)

Skaay refers

to Raven's

mother as

'Floodtide

Woman'.

|