|

TRANSLATIONS

The falcon (spirit of the sun) flies away in 15 Moan, according to my intuition, as if sun had been beheaded at full moon (the 15th night). Similarly, in 4 Zotz the spirit of the moon flies away like a bat. Bats fly erractically in the dark, falcons straight and in the light:

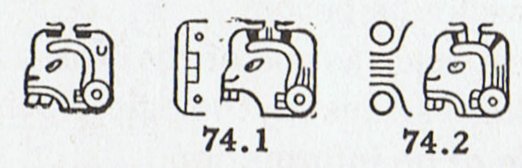

Symmetry demands another person to leave in 19 Vayeb, I think. If so, then it probably is the 'person' born in 16 Pax, the glyphs are similar. Gates has much relevant to say in this matter. His glyph number 74 is a suitable point from which to start: "... in 74 we have ... the top of the head flared, as we have seen elsewhere, on the signs for chuen, tun, to change them to Tzec, Pax, etc.

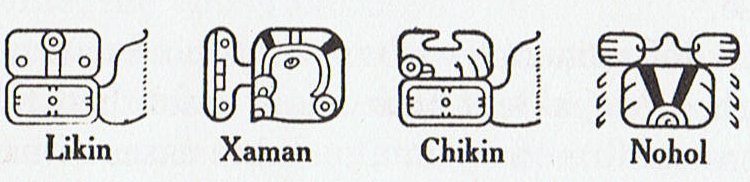

This 74 is used exclusively as a final through several long tzolkins in both codices, also the Paris." With 3 seasons (sun 10 * 20 = 200 days, person X born in 16 Pax and 'decapitated' in 19 Vayeb, and moon 4 * 20 = 80 nights) there ought to be 3 'birth' locations marked by open flare glyph types my intuition tells me. Number 74 is the missing 3rd birth glyph, I guess. If so, then it is person X who is giving birth (maybe because his head is used for the purpose) in 19 Vayeb, because the 'striped headband' in the Pax glyph is used as a sign also in 74. 74 was 'used exclusively as a final through several long tzolkins' - and the end means the beginning. As to the 'banded headdress', which is alluding to the tun wooden drum:  "We cannot call it a 'pottery decoration', on a clay tortilla griddle, in Maya xamach, and then say that these rim marks were added to the head of the god ruling Xaman, the North, as a rebus or 'ikonomatic' punning reminder of his name; and then on those grounds establish the Polar Star as a special god with this glyph. (Brinton, Primer.)" (Gates) The sign for north (Xaman) also has this 'banded headdress':  The tortilla griddle (xamach) surely must refer to the north, I think. The new year fire originated in the north (just as it presumably had to be fetched by way of the ariki of the island coming down from Anakena to Vinapu). The griddle we have met before, in form of a barbecue: ... For the Indians this group (minus Eridanus) consists of the five otters busy stealing the fish placed on a barbecue (Columba), by a fisherman armed with a net (stretched between Rigel, Betelgeuse, and three stars of the constellation Orion) ... Notably, the fire was fetched from Vinapu up to Hanga Hoonu according to the tale about the explorers: ... Again they went on and reached Hanga Hoonu. They saw it, looked around, and gave the name 'Hanga Hoonu A Hau Maka'. On the same day, when they had reached the Bay of Turtles, they made camp and rested. They all saw the fish that were there, that were present in large numbers - Ah! Then they all went into the water, moved toward the shore, and threw the fish (with their hands) onto the dry land. There were great numbers (? ka-mea-ro) of fish. There were tutuhi, paparava, and tahe mata pukupuku. Those were the three kinds of fish. After they had thrown the fish on the beach, Ira said, 'Make a fire and prepare the fish!' When he saw that there was no fire, Ira said, 'One of you go and bring the fire from Hanga Te Pau!' One of the young men went to the fire, took the fire and provisions (from the boat), turned around, and went back to Hanga Hoonu. When he arrived there, he sat down. They prepared the fish in the fire on the flat rocks, cooked them, and ate until they were completely satisfied. Then they gave the name 'The rock, where (the fish) were prepared in the fire with makoi (fruit of Thespesia populnea?) belongs to Ira' (Te Papa Tunu Makoi A Ira). They remained in Hanga Hoonu for five days. '... Compared with Hau Maka's vision, the experience involving the abundance of fish at Hanga Hoonu is new. This explains the additional name 'the basket (full of fish) between the thighs (which held the fish together)' (ko te kete kauhanga, TP:27) ...' They threw the fish with their hands onto dry land. The use of hands and the sudden change from sea to dry land definitely alludes to the radical change accomplished by a new year-fire. We also received an important lesson in form of the contrast between Hanga Hoonu and Hanga Te Pau.

The distance from Hanga Hoonu to Hanga Te Pau ougth to be - going forward in time - 96 * ½ + 84 * ⅔ + 84 * ⅓ * ½ = 48 + 56 + 14 = 118 = 2 * 59 days. Going back - which the young man did - means 365 - 118 = 247 = 13 * 19 days. The forward measure is counted by the moon (4 * 29.5 = 118), while the backward measure is counted by the sun. Moon is female in character, and open like the future. Sun is male and therefore looking back, closed for the future. 13 and 19 both indicate 'closed'. 48 was used as a basic measure in for instance K (we should remember):

If Ka2-10 should refer to Akahanga, Ka3-15 to Hanga Takaure and Kb1-11 to Hanga Hoonu, the distances will measure out Maunga Teatea (the very light mountain) in the middle:

Every glyph would have to cover 2 days. Mago in Ka4-14 is located as number 21, presumably a sign of a position 1 beyond the Ahau position:

I will soon return to the possible relationship between Imix and mago in Ka4-14 - it is impossible to investigate everything at once, it must done in a sequential manner. Moving from Akahanga to Hanga Takaure involves a mixed measure (84 and 96). 84 + 96 = 180, and half that gives 90 (a quarter of the year). But in K the glyph distance (given that Ka2-10 should refer to Akahanga etc) is 28 contra 48 for the glyph distance between Hanga Takaure and Hanga Hoonu. 4 * 7 = 28 and 4 * 12 = 48. It appears that there may be a quarter (of a year) between the Rei glyphs in K. There ought to be a quarter between the hanga stations in the kuhane journey too. But the 4th hanga is off its position even more so than Akahanga and also hidden between Te Kioe Uri and Te Piringa Aniva, viz. Hanga Te Pau. The distance from Hanga Te Pau to Akahanga ought to be 84 * ⅓ * ½ + 84 * ½ = 14 + 42 = 56 nights = 4 * 14 nights:

365 - 56 - 96 - 118 = 95. The distance from Akahanga to Hanga Takaure is not 90, i.e. (84 + 96) / 2, but 5 days more. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||