The reason for all this weeping might have been the absence of fresh agricultural food, the starving time before the return of the rainy season ('weeping'), without which there would be no 'off-spring'. Rain (ua) reversed should then, of course, mean fine weather ahead, a good time for fishing tours:

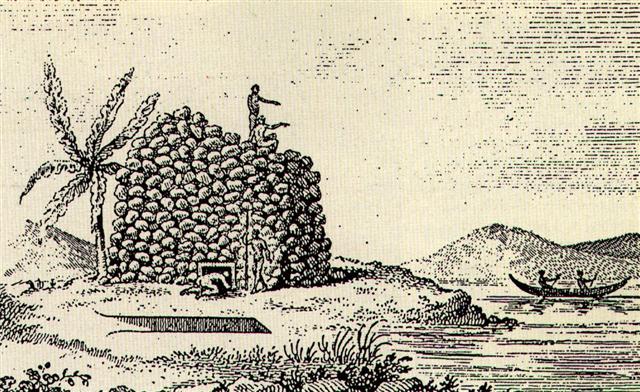

... another Alcyone, daughter of Pleione, 'Queen of Sailing', by the oak-hero Atlas, was the mystical leader of the seven Pleiads. The heliacal rising of the Pleiads in May marked the beginning of the navigational year; their setting marked its end when (as Pliny notices in a passage about the halcyon) a remarkably cold North wind blows ... ... According to an etiological Hawaiian myth, the breadfruit originated from the sacrifice of the war god Kū. After deciding to live secretly among mortals as a farmer, Ku married and had children. He and his family lived happily until a famine seized their island. When he could no longer bear to watch his children suffer, Ku told his wife that he could deliver them from starvation, but to do so he would have to leave them. Reluctantly, she agreed, and at her word, Ku descended into the ground right where he had stood until only the top of his head was visible. His family waited around the spot he had last been day and night, watering it with their tears until suddenly a small green shoot appeared where Ku had stood. Quickly, the shoot grew into a tall and leafy tree that was laden with heavy breadfruits that Ku's family and neighbors gratefully ate, joyfully saved from starvation ...

The breadfruit tree was bringing bread to the starving family. In the rongorongo idiom the 'breadfruit' was presumably illustrated as the type of glyph which I (relying on Metoro Tau'a Ure) have labelled hua poporo.

Poporo. A plant (Solanum forsteri); poporo haha, a sort of golden thistle. Vanaga. A berry whose juice is mixed with ashes of ti leaves in tattoing. Ta.: oporo, a capsicum plant. The Tahiti oporo is not a degradation of poporo but is the original poro stem augmented by that o which in Tahiti is word-formative in a sense too elusive to find expression in European ideas. Mgv.: poporo, the July season when the leaves fall. Mq.: pororo, dry, arid. Sa.: palolo-mua, July. Ma.: paroro, cloudy weather. Poporohiva, milk thistle. Churchill. The palolo worm or Samoan palolo worm (Palola viridis) is a species of invertebrate in the Eunicidae family:

... The lolo reappears in such parts of Nuclear Polynesia as have the animal as a component of Samoa palolo, Tonga balolo, Viti mbalolo. I cite a note on this subject which I wrote out for Dr. William McMichael Woodworth, who identified the palolo as the posterior epitokal part of Eunice viridis (Gray): Stair's derivation from pa'a-lolo, luscious crab, is out of all consideration; it is on all fours with the classic definition of a crab as a small red fish that walks backward, for pa'a (paka) could not in the Samoan system of word structure undergo such a syncopation as to cut itself in two. As the bit beastie is in no sense a crab, and I must claim for my islanders that their intelligence is sufficiently high to prevent them from putting two such dissimilar animals together, so in turn is lolo not luscious. The organs of sense perception by which the Samoans apperceives lolo lie, not in the peripheral nerve endings of the tongue, but of the fingers; it is a matter of touch and not of taste such as luscious principally connotes. I got a very instructive glimpse at this word from my cook boy and a dish of vermicelli soup. After it had served my uses the tureen went back to the kitchen. I found the servitor dabbling his fingers in the dish, which he pronounced to be fa'alolo. I regard the primal significance as one of consistency, somewhat custardy, a substance partially solid that may to a certain extent be grasped in the fingers yet which seems to slip out and elude the grasp. That, it will be noticed, is a thread that can be run through all the significations. It applies equally well to the palolo as you feel it in the water on the great day of its appearance. In the slightly specialized sense of slippery it applies similarly to its other two compounds in the Samoan, ngalolo and umelolo, both being fishes and the latter a variety of Naseus lituratus or unicornis. Churchill 2. The hanging droplets ('watery eyes') might have referred to the season of breadfruit. ... He points out that in the Marquesas they counted the fruits from the breadfruit trees in fours, perhaps thereby explaining the four 'berries' in this type of glyph. The breadfruit did not grow on Easter Island but the berries of Solanum nigrum were eaten in times of famine. Barthel compares with the word koporo on Mangareva. The poor crop of breadfruits at the end of the harvest season was called mei-koporo, where mei stood for breadfruit. On other islands breadfruit was called kuru, except in the Marquesas which also used the word mei. Koporo was a species of nightshade ... ... In Tahiti the bread-fruit can be gathered for seven months, for the other five there is none: for about two months before and after the southern solstice it is very scarce, but from March to August exceedingly plentiful. This season is called pa-uru (uru = 'bread-fruit'). The recurring scarcity of bread-fruit shewed the changes in the course of the year, but the Pleiades afforded a surer limit. In Samoa one authority gives the wet season, ending in April, and the dry season, which comes to an end with the palolo fishing in October; another vaipalolo the palolo or wet season from October to March, and toe lau, when the regular trade-winds blow, embracing the other months; a third the season of fine weather - in which however much rain falls in some localities - and the stormy season, when it rains heavily ... (Nilsson) Presumably the pair of seasons - water and drought - motivated the design of Ca1-19--20:

The point of change was evidently - at least according to the creator of the C text - where in April 10 (100) the season of drought (relying on fishes for food instead of land crops) began;. north of the equator when the Sun reached April 10 and south of the equator when April 10 was at the Full Moon. ... Hamiora Pio once spoke as follows to the writer: 'Friend! Let me tell of the offspring of Tangaroa-akiukiu, whose two daughters were Hine-raumati (the Summer Maid - personified form of summer) and Hine-takurua (the Winter Maid - personification of winter), both of whom where taken to wife by the sun ... Now, these women had different homes. Hine-takurua lived with her elder Tangaroa (a sea being - origin and personified form of fish). Her labours were connected with Tangaroa - that is, with fish. Hine-raumati dwelt on land, where she cultivated food products, and attended to the taking of game and forest products, all such things connected with Tane ...

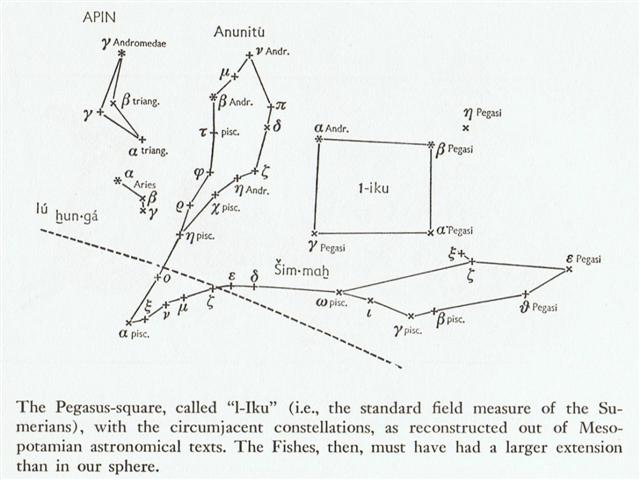

Here we can see how the pair of celestial bands (with light close to the Pegasus Square and Andromeda) had Knees (Ksora).

The celestial bands were not crossing over each other, they were no longer 'bound together in close embrace'.

... The Katawihi distinguish two rainbows: Mawali in the west, and Tini in the east. Tini and Mawali were twin brothers who brought about the flood that inundated the whole world and killed all living people, except two young girls whom they saved to be their companions. It is not advisable to look either of them straight in the eye: to look at Mawali is to become flabby, lazy, and unlucky at hunting and fishing; to look at Tini makes a man so clumsy that he cannot go any distance without stumbling and lacerating his feet against all obstacles in his path, or pick up a sharp instrument without cutting himself ... ... The Mura also believed that there were two rainbows, an 'upper' and a 'lower' ... Similarly, the Tucuna differentiated between the eastern and the western rainbows and believed them both to be subaquatic demons, the masters of fish and potter's clay respectively ... ... In South America the rainbow has a double meaning. On the one hand, as elsewhere, it announces the end of rain; on the other hand, it is considered to be responsible for diseases and various natural disasters. In its first capacity the rainbow effects a disjunction between the sky and the earth which previously were joined through the medium of rain. In the second capacity it replaces the normal beneficient conjunction by an abnormal, maleficient one - the one it brings about itself between sky and earth by taking the place of water ... Which, in turn, will make us recognize this Sign at the reverse side of the Janus coin. Drought and fine weather was at Argo Navis in July whereas Rain and a good time for sowing was at Janus:

Canopus (365 Carinae) consumed all the waters and therefore Argo Navis ought to have indicated drought and a need to move out at sea in order to get food.

Its stern - where old men and women with child were sitting - was uplifted while the front half went down.

... It is an interesting fact, although one little commented upon, that myths involving a canoe journey, whether they originate from the Athapaskan and north-western Salish, the Iroquois and north-eastern Algonquin, or the Amazonian tribes, are very explicit about the respective places allocated to passengers. In the case of maritime, lake-dwelling or river-dwelling tribes, the fact can be explained, in the first instance, by the importance they attach to anything connected with navigation: 'Literally and symbolically,' notes Goldman ... referring to the Cubeo of the Uaupés basin, 'the river is a binding thread for the people. It is a source of emergence and the path along which the ancestors had travelled. It contains in its place names genealogical as well as mythological references, the latter at the petroglyphs in particular.' A little further on ... the same observer adds: 'The most important position in the canoe are those of stroke and steersman. A woman travelling with men always steers, because that is the lighter work. She may even nurse her child while steering ... On a long journey the prowsman or stroke is always the strongest man, while a woman, or the weakest or oldest man is at the helm ...

Manuscript E:92-97: Hotu stayed [he noho] in Hare Tupa Tuu. The servant (tuura) of Tuu Maheke, namely Rovi [te tuura.o Tuu maheke.ko Rovi], prepared the food for Tuu Maheke [he hangai i a Tuu maheke]. Tuu Maheke stayed in Hare Tupa Tuu because of this servant, Rovi. The earth-oven, the lighting of fire (tumuteka; emulation te umu te ka), and the cooking (te tao) were the responsibilities of Rovi.When it was time to place (the food) into the earth-oven, to take out (the prepared food), and to take (the meal into the house) to the king, to Tuu Maheke, only Rovi was allowed to be there. He alone could supply the king, Tuu Maheke, with food. In this manner Tuu Maheke had reached (the age of) fifteen. Rovi took the eel trap. He picked it up and went to the sea to catch eel, which were supposed to be a side dish (inaki) for King Tuu Maheke's sweet potatoes [te kumara.o te ariki.a Tuu maheke]. He stayed there and went about catching eels. But Rovi stayed late catching eels, and Tuu Maheke became hungry while he waited all by himself. Night came, and King Tuu Maheke remained without food. When King Tu Maheke grew hungry, he sat down inside the house and cried [he noho-he tangi.i roto i te hare.tupa tuu]. He was all alone [hokotahi] in Hare Tupa Tuu because [no] the mother (too) had gone away to dig up sweet potatoes [te matua tamatahine.ku oho ana ki te kumara are], and cook them in the earth-oven [mo tao], and roast them, and bring them to the king. Hotu saw Tuu Maheke's weeping [he tikea te tanginga.o Tuu maheke.e Hotu]. When the royal child (ariki poki) continued to cry [ku tangi mai era ana.te ariki poki], the father became angry because of the continued lamentation of King Tuu Maheke [i te tangihanga no atu.o te ariki.o Tuu maheke]. King Hotu arose [he ea.mai.te ariki.a Hotu] and went from his house to the front of the house of Tuu Maheke, which was a distance away [he oho.mai mai toona hare.ki mua ki te hare.o Tuu maheke]. After he had waited there and observed the weeping [i ui mai ai.ki te tangihanga] of Tuu Maheke, the father called out [he rangi] the following, while the child continued to cry [e tangi era te poki], 'Be still [ka mou], you bastard (morore), you crybaby rava tangi) day after day [te raa.te raa]! One could loose one's eyebrows (i.e., one gets a headache) from this eternal crying morning after morning (? apo apo apo)!' Tuu Maheke heard his father calling, and [? Rather: When the calling out, rangihanga, of his father had finished, he ngaroa] the child continued to cry [ka tangi no te poki]. The father [tangata matua] got up [he ea], went [rather: returned] to his house, and stayed there [he hoki he oho.ki toona hare he noho]. The mother [vie matua] came back [he tuu] from harvesting sweet potatoes [te kumara keri]. She came at the moment when the eyes of the king were still swollen from crying. The mother asked [he ui] the child, 'What is wrong, oh king, that you are crying and the eyes of the king are swollen from crying.' [ku ahuahu ana te mata o te ariki i te tangihanga] The boy (kope) answered the following [he ki mai tau kope era.penei ē], 'There is this person, and I am crying because of him. The bad man [tangata rakerake] shouted [he rangi] at me (deletion) like this [penei ē]: 'Be still [ka mou], you bastard [te morore], you crybaby [ravatangi]! One gets a headache [ku motu ana.te hihi] from your whining [i te ravatangihanga] day after day [te raa te raa].' That's how it was [peirā]. After he had shouted at me like this [i rangi mai ai kia au], he returned to his house and stayed there [he hoki atu ki toona hare he noho].' The mother got up, went away, arrived, and lit the earth-oven[he ea.tau vie matua era.he oho.he tuu he kā i te umu]. She roasted the sweet potatoes, took a dish, picked up (the meal), came, [he tao(m)i i te kumara.he kokohu.he mau he oho.mai] and entered (the house of) King Tuu Maheke from the rear [he hakauru mai a tua.ki te ariki.kia Tuu maheke]. Then she turned around, arrived, and placed the food into the earth-oven [he hoki he oho.he tuu.he uru i te umu]. She cooked it and finished the cooking in the earth-oven [he tao.he oti te tao i te umu]. The earth-oven of Vakai and the cooking were finished [ku oti ana te umu.a Vakai.te tao] when the servant of the king, namely Rovi, arrived [i tuu mai ai te tuura.o te ariki.ko Rovi]. He went to his earth-oven and lit it (to be able) to prepare (food) for the king in it [he tuu mai ia ki taana.umu.he ka mo hakauru mo te ariki]. Vakai arose, went away, arrived, and quarreled with [he kakai kia] Hotu in the following manner [penei ē]: 'Why did you shout [heaha.koe.e rangi] bad things [te kī rakerake] at King Tuu Maheke! This is how it is [penei ē] - King Tuu Maheke is not a bastard! [he morore ō te ariki.a Tuu maheke]' Vakai added: 'You yourself are a bastard and a scabby head (puoko havahava) of Tai A Mahia! Kokiri Tuu Hongohongo was your father (i.e., he raised your) back (i.e., in the west) in Oti Onge (literally, where the hunger ends) in Hiva, because he was told to do so by Taana A Harai!' To this speech King Hotu answered [he hakahoki] the following (analogous translation): 'Oh little mother, why did you not tell me this in Hiva, in our homeland?' The woman arose [he ea tau vie era], turned around, went back to her house, and stayed there. Hotu arose [he ea.a Hotu], moved (his residence) a short distance away [he neke.iti atu.he hakapehiva iti.ātu], and settled down. He finished building the house [he āto.i toona hare] and covering the roof [he oti te hare.te ato], and now he lived in Hare Pu Rangi [he noho.i hare pu rangi]. When another month had come [he tuu], Vakai set out again [he ea.atu a Vakai]. She went and entered into the house, into Hare Pu Rangi [he ōho.he oō ki roto ki hare pu rangi]. She lived in the house of King Hotu [he noho.i roto i te hare o te ariki.o Hotu] while Tuu Maheke stayed by himself [ka noho no.te ariki.a Tuu maheke] in his own house [i toona hare ana], in Hare Tupa Tuu, with his servant Rovi [i hare tupa tuu.ko toona tuura tokoa.ko Rovi].

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)