Significantly the place with a dot was in the day after the Head of Hercules, when Al-risha (the Knot) culminated (at 21h). Although the distance from heliacal Sirrah (*0.5) to heliacal Alrisha (*29.2) was 29 days, the distance between their culminations was only 26 (= 341 - 315) days. The cycle of the Earth around the Sun was not a perfect circle.

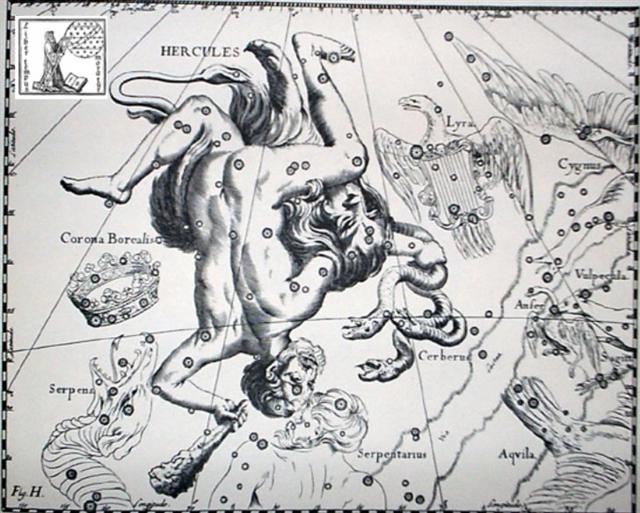

Counting (hia) from Capella and Rigel at the Sun there were 177 (= 6 * 29½) days to hakaariki and 182 (= 364 / 2) days to Ras Algethi.

The Head of the King (Tupu) depicted at Capella and Rigel was presumably corresponding (as reflected in a mirror) to the Head of Hercules (Ras Algethi). There were 2 cycles in a year and therefore Tupu te toromiro ought to have referred to a place 366 / 2 days earlier (or later) in the rongorongo text. ... The Celtic year was divided into two halves with the second half beginning in July, apparently after a seven-day wake, or funeral feast, in the oak-king's honour ... In the G text hakaariki was placed at Cursa (the Footstool of the Giant Orion):

Nihal (β Leporis - i.e. the 'Thirst-slaking Camels') was a star rising 3 days after Capella / Rigel and thus in a way like the mirror image of Rei (with a Capital letter) at the Sting of the Scorpion (Lesath). ... 'The life-force of the earth is water. God moulded the earth with water. Blood too he made out of water. Even in a stone there is this force, for there is moisture in everything. But if Nummo is water, it also produces copper. When the sky is overcast, the sun's rays may be seen materializing on the misty horizon. These rays, excreted by the spirits, are of copper and are light. They are water too, because they uphold the earth's moisture as it rises. The Pair excrete light, because they are also light ... 'The sun's rays,' he went on, 'are fire and the Nummo's excrement. It is the rays which give the sun its strength. It is the Nummo who gives life to this star, for the sun is in some sort a star.' It was difficult to get him to explain what he meant by this obscure statement. The Nazarene made more than one fruitless effort to understand this part of the cosmogony; he could not discover any chink or crack through which to apprehend its meaning. He was moreover confronted with identifications which no European, that is, no average rational European, could admit. He felt himself humiliated, though not disagreeably so, at finding that his informant regarded fire and water as complementary, and not as opposites. The rays of light and heat draw the water up, and also cause it to descend again in the form of rain. That is all to the good. The movement created by this coming and going is a good thing. By means of the rays the Nummo draws out, and gives back the life-force. This movement indeed makes life. The old man realized that he was now at a critical point. If the Nazarene did not understand this business of coming and going, he would not understand anything else. He wanted to say that what made life was not so much force as the movement of forces. He reverted to the idea of a universal shuttle service. 'The rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world.' ...

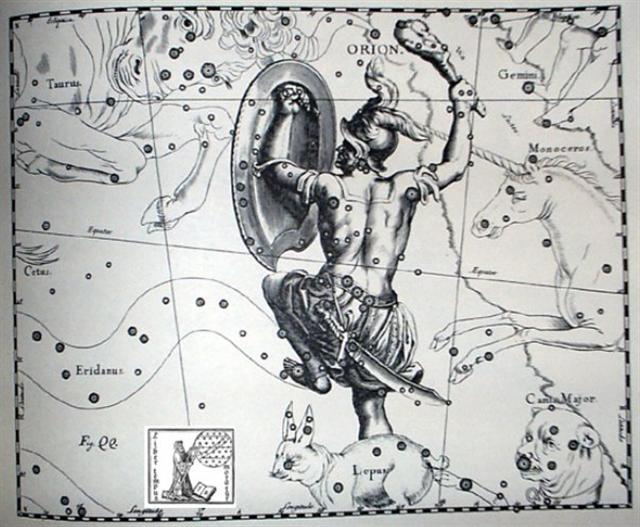

Orion was the same person as Hercules and his shadow (tanist) was Serpentarius - as we can see in the illustrations of Hevelius (and his wife).

... Gronw Pebyr, who figures as the lord of Penllyn - 'Lord of the Lake' - which was also the title of Tegid Voel, Cerridwen's husband, is really Llew's twin and tanist ... Gronw reigns during the second half of the year, after Llew's sacrificial murder; and the weary stag whom he kills and flays outside Llew's castle stands for Llew himself (a 'stag of seven fights'). This constant shift in symbolic values makes the allegory difficult for the prose-minded reader to follow, but to the poet who remembers the fate of the pastoral Hercules the sense is clear: after despatching Llew with the dart hurled at him from Bryn Kyvergyr, Gronw flays him, cuts him to pieces and distributes the pieces among his merry-men. The clue is given in the phrase 'baiting his dogs'. Math had similarly made a stag of his rival Gilvaethwy, earlier in the story. It seems likely that Llew's mediaeval successor, Red Robin Hood, was also once worshipped as a stag. His presence at the Abbot's Bromley Horn Dance would be difficult to account for otherwise, and stag's horn moss is sometimes called Robin Hood's Hatband. In May, the stag puts on his red summer coat. Llew visits the Castle of Arianrhod in a coracle of weed and sedge. The coracle is the same old harvest basket in which nearly every antique Sun-god makes his New Year voyage; and the virgin princess, his mother, is always waiting to greet him on the bank ...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||