On page E:63 has been listed what at first appears to be 31 - 13 = 18 more varieties of yam - which we could associate with my suggested 31 * 13 = 403 = 280 + 123 days from Ga2-27 (MAY 17, 137) up to and including Ga7-10 (SEPTEMBER 16, 259).

However, there is a hole (a gap - as in Al Nathrah at the Beehive)

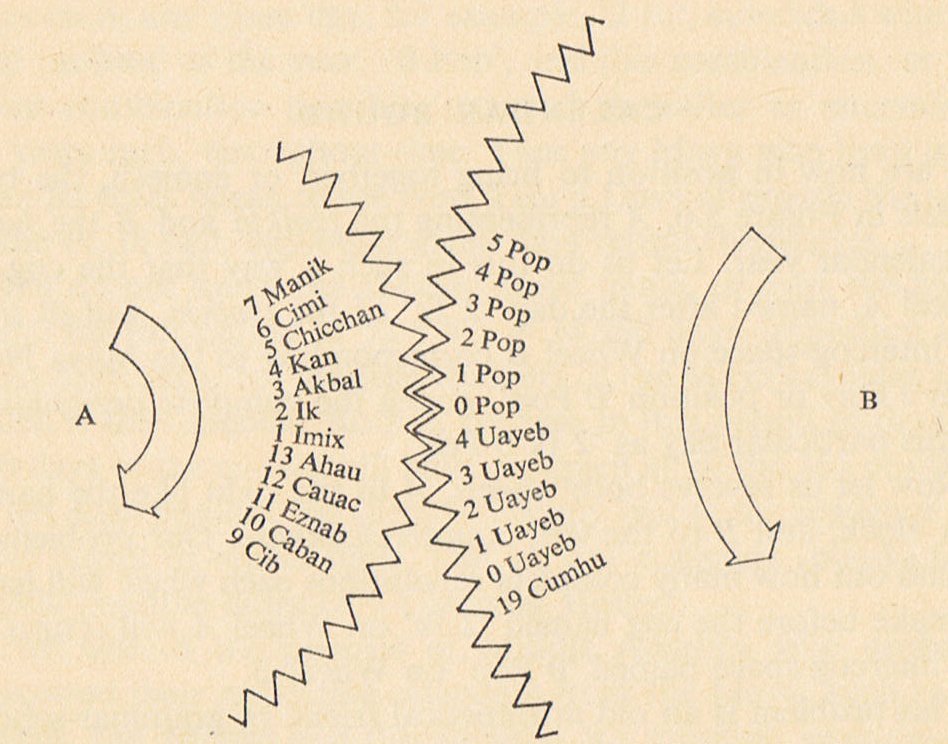

in the list between item 18 and 20, which means the number of varietes of yams was not 41 (as I earlier prematurely have stated) but 40. Inspired by this fact I then searched further ahead and indeed found another such gap between item 32 and 34. Which means the total number was neither 41 nor 40 but 39 (= 3 * 13 → 314 - 1). ... The Maya Indians had several calendars, the one I have used here is their calendar over the year (haab). It was used in conjunction with the more famous tzolkin (for their sacred year), which was composed by the numbers from 1 to 13 prefixed to one of their 20 daynames, for instance as 13 Ahau - the last of the 13 numbers conjoined with the last of the 20 daynames (Ahau). This gave 13 * 20 = 260 possible dates according to the tzolkin. In the picture below (ref.: Midonick) is explained how a more definite date is generated by combining tzolkin with haab:

Also the ordinal number in the month according to the haab calendar was prefixed (see B cogwheel). But the counting began with 0 instead of with 1 (cfr for instance 1 Imix in the A cogwheel, the tzolkin). The last (19th) haab month (Vayeb - or as spelled in the picture: Uayeb) had only 5 days, and its highest number therefore became 4. Otherwise the highest number in a month was 19. Months were defined in the haab calendar, not in the tzolkin ... As to the names we should notice how 3 colours (uri, tea, mea) were followed by para (item 17): Para. 1. Spleen. 2. Ripe; to ripen: maîka para, ripe bananas; para rautí said of ripe bananas the peel of which has stayed green. 3. To start rotting (of wood and other materials): ku-para-á te miro, the wood has rotted. 4. A moss found in abundance in the watery bottom of Rano Kau, which has very long roots laden with water. Fishermen used to take quantities of them, wrapped in banana leaves, to alleviate their thirst. Vanaga. 1. A short club T. Mq.: parahua, a paddle-shaped club. 2. To become bad, to soften, to decay, to rot, to ripen, old, used up.; niho para, decayed teeth; para rakerake, overripe; tae para, unripe. Hakapara, to mellow. P Mgv.: para, ripe, mature; akapara, to ripen, to improve morally. Mq.: paá, ripe, soft, overripe, rotten, old, used up. Ta.: para, ripe. 3. Spleen. Churchill. Hei para, 'ripening', this term refers to the time when such plants as the banana or sweet potato lose their fresh green colour and become yellow, which is taken as a symbol of bad omen or of death in the family. Vanaga. Hega. Hegahega, reddish, ruddy. Hehega, to dawn; ki hehega mai te raá, when the sun rises. Vanaga. Hehegaraa, sunrise. PS Sa.: sesega, to be dazzled as by the sun. Fu.: sega, the beginning of daybreak. Niuē: hegahega, the red light or rays at sunset. Viti: sesē, to dawn. Churchill. ... Oti and Parahenga [Bara henga] went into the house [ki roto ki te hare], picked up [he too mai] the figure, put her on a stretcher (rango) and carried her on board the canoe. (There) they left her ... In Sweden number 17 is commonly used to express extreme disgust ('fy sjutton'). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||