This outstretched Bull's leg had, according to myth, been thrown in the face of Ishtar:

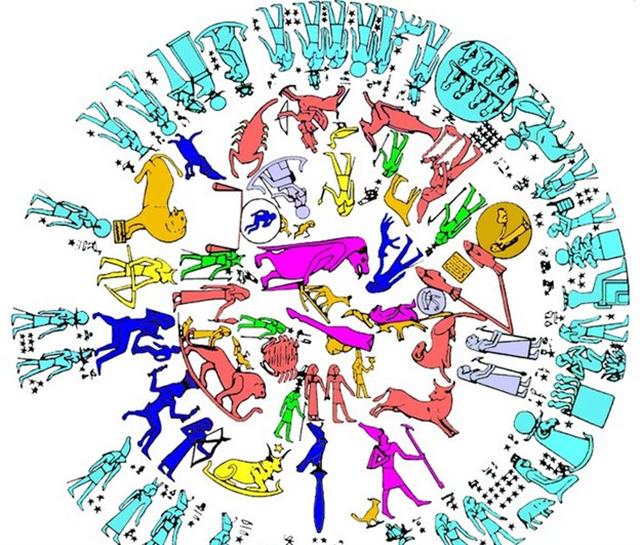

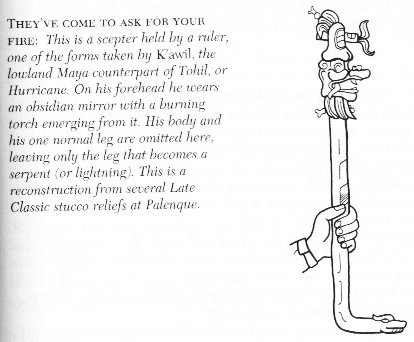

... Ishtar, scorned, goes up to heaven in a rage, and extracts from Anu the promise that he will send down the Bull of Heaven to avenge her. The Bull descends, awesome to behold. With his first snort he downs a hundred warriors. But the two heroes tackle him. Enkidu takes hold of him by the tail, so that Gilgamesh as espada can come in between the horns for the kill. The artisans of the town admire the size of those horns: 'thirty pounds was their content of lapis lazuli'. (Lapis lazuli is the color sacred to Styx, as we have seen. In Mexico it is turquoise.) Ishtar appears on the walls of Uruk and curses the two heroes who have shamed her, but Enkidu tears out the right thigh of the Bull of Heaven and flings it in her face, amidst brutal taunts. It seems to be part of established procedure in those circles. Susanowo did the same to the sun-goddess Amaterasu, and so did Odin the Wild Hunter to the man who stymied him. A scene of popular triumph and rejoicings follows. But the gods have decided that Enkidu must die, and he is warned by a somber dream after he falls sick. The composition of the epic has been hitherto uncouth and repetitious and, although it remains repetitious, it becomes poetry here. The despair and terror of Gilgamesh at watching the death of his friend is a more searing scene than Prince Gautama's 'discovery' of mortality. 'Hearken unto me, O elders, (and give ear) unto me! // It is for Enk(idu), my friend, that I weep, // Crying bitterly like unto a wailing woman // (My friend), my (younger broth)er (?), who chased // the wild ass of the open country (and) the panther of the steppe. // Who seized and (killed) the bull of heaven; // Who overthrew Humbaba, that (dwelt) in the (cedar) forest - ! // Now what sleep is this that has taken hold of (thee)? // Thou hast become dark and canst not hear (me)'. // But he does not lift (his eyes). // He touched his heart, but it did not beat. // Then he veiled (his) friend like a bride (...) // He lifted his voice like a lion // Like a lioness robbed of (her) whelps ... 'When I die, shall I not be like unto Enkidu? // Sorrow has entered my heart // I am afraid of death and roam over the desert ... // (Him the fate of mankind has overtaken) // Six days and seven nights I wept over him // Until the worm fell on his face. // How can I be silent? How can I be quiet? // My friend, whom I loved, has turned to clay' ... And among the Mayas this mythic leg was explained as belonging to Tohil: ... They walked in crowds when they arrived at Tulan, and there was no fire. Only those with Tohil had it: this was the tribe whose god was first to generate fire. How it was generated is not clear. Their fire was already burning when Jaguar Quitze and Jaguar Night first saw it: 'Alas! Fire has not yet become ours. We'll die from the cold', they said. And then Tohil spoke: 'Do not grieve. You will have your own even when the fire you're talking about has been lost', Tohil told them. 'Aren't you a true god! Our sustenance and our support! Our god!' they said when they gave thanks for what Tohil had said. 'Very well, in truth, I am your god: so be it. I am your lord: so be it,' the penitents and sacrificers were told by Tohil. And this was the warming of the tribes. They were pleased by their fire. After that a great downpour began, which cut short the fire of the tribes. And hail fell thickly on all the tribes, and their fires were put out by the hail. Their fires didn't start up again. So then Jaguar Quitze and Jaguar Night asked for their fire again: 'Tohil, we'll be finished off by the cold', they told Tohil. 'Well, do not grive', said Tohil. Then he started a fire. He pivoted inside his sandal ...

... He was moreover confronted with identifications which no European, that is, no average rational European, could admit. He felt himself humiliated, though not disagreeably so, at finding that his informant regarded fire and water as complementary, and not as opposites. The rays of light and heat draw the water up, and also cause it to descend again in the form of rain. That is all to the good. The movement created by this coming and going is a good thing. By means of the rays the Nummo draws out, and gives back the life-force. This movement indeed makes life. The old man realized that he was now at a critical point. If the Nazarene did not understand this business of coming and going, he would not understand anything else. He wanted to say that what made life was not so much force as the movement of forces. He reverted to the idea of a universal shuttle service. 'The rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world' ...

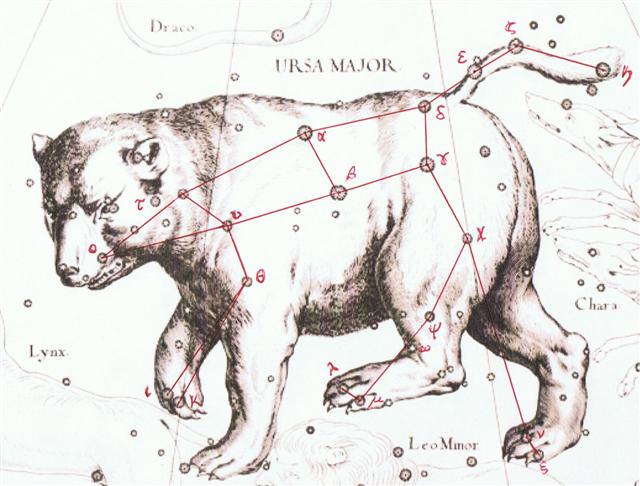

The Egyptians identified their Thigh of the Bull with Ursa Major.

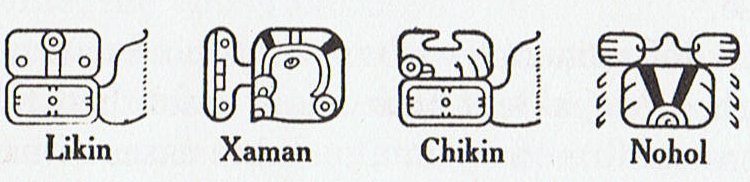

When Ursa Major (alias 7-Macaw alias Itzam-Yeh) had ruled at the top it could be imagined that his turning around (viri) caused friction, which in turn would have produced fire. But then he had been pulled down, possibly where the Wolf changed into the Dog (the first of the domesticated beasts):

We can count: 3149 BC + 1842 AD (my assumed epoch for rongorongo) = 8140 years, and with the pace of the precession measured as 26000 / 365.25 = 71.184 years, the present right ascension position (i.e., according to my assumed epoch of rongorongo) would then have been *27.4 (Sheratan) + *8140 / 71.184 = ca *141.75:

The end (final) of the Serpent (water) was like the accumulated dry old skins of a rattle snake. ... the instruments of darkness which replace the bells include the hammer, the hand rattle, the clapper or hand-knocker, a kind of castanets called 'livre', the matraca (a flat slab of wood with two movable plates attached to each either side which strike it when it is shaken) and the wooden sistrum on a string or a ring. Other instruments, such as the batelet and huge rattles, were quite complicated pieces of apparatus. In theory, all these devices had a definite function, but in actual practice they often overlapped: they were used to make a noise inside the church or out, to summon the congregation in the absence of bells, or to accompany the collecting of alms by children. There is, also, some evidence that the instruments of darkness may have been intended to represent the marvels and terrifying noises which occurred at the time of the death of Christ ... ... In China, every year about the beginning of April, certain officials called Sz'hüen used of old to go about the country armed with wooden clappers. Their business was to summon the people and command them to put out every fire. This was the beginning of the season called Han-shih-tsieh, or 'eating of cold food'. For three days all household fires remained extinct as a preparation for the solemn renewal of the fire, which took place on the fifth or sixth day after the winter solstice [Sic!] ... ... a storm is a weak form of an eclipse, and the Guayaki myth offers the additional interest of associating smoke from bees' wax with acousic operations, to which must be added the explosion made by dry bamboo canes when thrown into the fire (Métraux-Baldus, p. 444), a noise which, as a strong manifestation of the sound of instrumens of the parabára type, links up 'honey smoke' with the instruments of darkness, just as 'tobacco smoke' is linked with rattles ... ... Moreover, Manethus says that the Egyptians have a mythical tradition in regard to Jupiter, that because his legs were grown together he was not able to walk and so for shame tarried in the wilderness; but Isis, by severing and separating those parts of his body, provided him with means of rapid progress. This fable teaches by its legend that the mind and reason of the god, fixed amid the unseen and invisible, advanced to generation by reason of motion. The sistrum, a metallic rattle, also makes it clear that all things in existence need to be shaken, or rattled about, and never to cease from motion but, as it were, to be waked up and agitated when they grow drowsy and torpid. They say that they avert and repel Typhon by means of the sistrum, indicating thereby that when destruction constricts and checks Nature, generation releases and arouses it by means of motion ...

Thus Itzam-Yeh had presumably been shot down when once upon a time the Sun reached the Nose of the Lion. This was about a week after the Great Bear had lifted up her right front paw (Talitha, the First Spring of the Gazelle):

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||