|

”Tiāmat, according to Jensen, means initially the Eastern Sea (p. 307). This was expanded to mean the ‘Weltwasser’ (p. 315), which may be taken to mean, I suppose, the origin of the Greek ωκεανος, and possibly the overlying firmament of waters. These firmamental waters contain the southerly ecliptic constellations, the winter and bad-weather signs – the Scorpion, the Goat-fish, and the Fish among them.

It must be pointed out that these southerly constellations were associated with the God of Eridu in his first stage.

The Constellations referred to in the Myth of Marduk and Tiāmat.

We are indebted to the myth, then, for the knowledge that when it was invented, not only the constellations Bull and Scorpion, but also the Goat and Fishes had been estblished in Babylonia. This argument is strengthened by Jensen:

‘We look in vain among the retinue of Tiāmat for an animal corresponding to the constellations of the zodiac to the east of the vernal equinox. This cannot be accidental. If, therefore, we contended that the cosmogonic legends of the Babylonians stood in close relationship to the phenomenon of sunrise on the one hand and the entrance of the sun into the vernal equinox on the other – that, in fact, the creation legends in general reflect these events – there could not be a more convincing proof of our view than the fact just mentioned.

The three monsters of Tiāmat, which Marduk overcomes, are located in the ‘water-region’ of the heavens, which the Spring-Sun Marduk ‘overcomes’ before entering the (ancient) Bull. If, as cannot be doubted, the signs of the zodiac are to be regarded as symbols, and especially if a monster like the goat-fish, whose form it is difficult to recognise in the corresponding constellation, can only be regarded as a symbol, then we may assume without hesitation that at the time when the Scorpion, the Goat-Fish, and the Fish were located as signs of the zodiac in the water-region of the sky, they already played their parts as the animals of Tiāmat in the creation legends.

Of course they were not taken out of a complete story and placed in the sky, but conceptions of a more general kind gave the first occasion. It does not follow that all the ancient myths now known to us must have been available, but certainly the root-stock of them, perhaps in the form of unsystematic and unconnected single stories and concepts.’

There is still further evidence for the constellation of the Scorpion:

‘A Scorpion-Man plays also another part in the cosmology of the Babylonians. The Scorpion-Man and his wife guard the gate leading to the Māśu mountain(s), and watch the sun at rising and setting. Their upper part reaches to the sky, and their irtu (breast ?) to the lower regions (Epic of Gistubar 60,9).

After Gistubar has traversed the Māśu Mountain, he reaches the sea. This sea lies to the east or south-east. However obscure these conceptions may be, and however they may render a general idea impossible, one thing is clear, that the Scorpion-Men are to be imagined at the boundary between land and sea, upper and lower world, and in such a way that the upper or human portion belongs to the upper region, and the lower, the Scorpion body, to the lower.

Hence the Scorpion-Man represents the boundary between light and darkness, between the firm land and the water region of the world. Marduk, the god of light, and vanquisher of Tiāmat, i.e. the ocean, has for a symbol the Bull – Taurus, into which he entered in spring.

This leads almost necessarily to the supposition that both the Bull and the Scorpion were located in the heavens at a time when the sun had its vernal equinox in Taurus and its autumnal equinox in Scorpio, and that in their principal parts or most conspicious star groups; hence probably in the vicinity of Aldebaran and Antares, or at an epoch when the principal parts of Taurus and Scorpio appeared before the sun at the equinoxes.’

If my suggestion be admitted that the Babylonians dealt not with the daily fight but with the yearly fight between light and darkness - that is, the antithesis between day and night was expanded into the antithesis between the summer and the winter halves of the year – then it is clear that at the vernal equinox Scorpio setting in the west could be watching the sunrise; at the autumnal equinox rising in the east, it would be watching the sunset; one part would be visible in the sky, the other would be below the horizon in the celestial waters. If this be so, all obscurity disappears, and we have merely a very beautiful statement of a fact, from which we learn that the time to which the fact applied was about 3000 B.C., if the sun were then near the Pleiades.

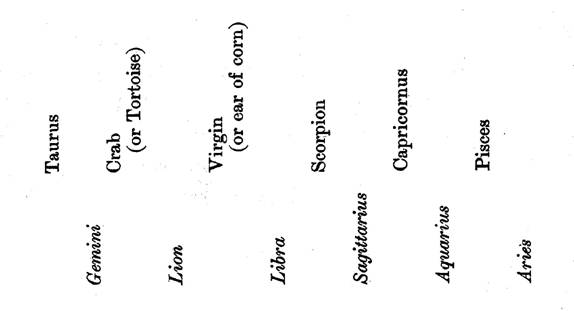

Jensen, in the above-mentioned passage by implication, and in a subsequent one directly, suggests that not all the zodiacal constellations were established at the same time. The Babylonians apparently began with the easier problem of having six constellations instead of twelve. For instance, we have already found that to complete the present number, between

Scorpio Capricornus [the Goat-fish] Pisces [the Fish]

we must interpolate

Sagittarius Aquarius [the Amphora]

Aries and Libra seem also to be late additions according to Jensen, who writes:

‘We have already above (p. 90) attempted to explain the striking phenomenon that the Bull and Pegasus, both with half-bodies only, ήμίτομοι, enclose the Ram between them, by the assumption that the latter was interposed later, when the sun at the time of the vernal equinox was in the hind parts of the Bull, so that this point was no longer sufficiently marked in the sky.

Another matter susceptible of a like explanation may be noted in the region of the sky opposite to the Ram and the Bull. Although we cannot doubt the existence of an eastern balance, still, as already remarked (p. 68), the Greeks have often called it χηλαί ‘claws’ (of the Scorpion), and according to what has been said above (p. 312), the sign for a constellation in the neighbourhood of our Libra reads in the Arsacid inscription ‘claw(s)’ of the Scorpion.

These facts are very simply explained on the supposition that the Scorpion originally extended into the region of the Balance, and that originally α and β Libræ represented the ‘horns’ of the Scorpion, but later on, when the autumnal equinox coincided with them, the term Balance was applied to them. Although this was used as an additional name, it was only natural that the old term should still be used as an equivalent. But it also indicates the great age of a portion of the zodiac.’

Let us suppose that what happened in the case of Aries and Libra happened with six constellations out of the twelve: in other words, that the original zodiac consisted only of six constellations.

The upper list not only classifies in an unbroken manner the Fish-Man, the Goat-Fish, the Scorpion-Man, and Marduk of the Babyloniana, but we pick up all or nearly all of the ecliptic stars or constellations met with in early Egyptian mythology, Apis, The Tortoise1, Min, Serk-t, Chnemu, as represented by appropriate symbols.”

1 I think I am right about the Tortoise, for I find the following passage in Jensen, p. 65, where he notes the absence of the Crab: ‘Ganz absehend davon, ob dasselbe für unsere Frage von Wichtigkeit werden wird oder nicht, muss ich daran erinnern, das unter den Emblemen, welche die sogenannten ‘Deeds of Salè’ häufig begleiten, verschiedene Male wie der Scorpion so die Schildkröte abgebildet gefunden wird’.

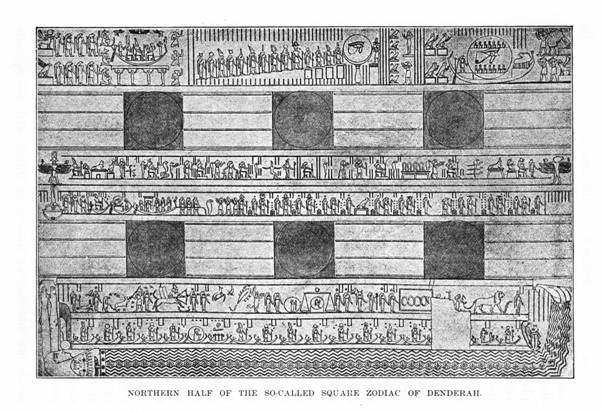

This picture evidently contains an enormous amount of information and I have preserved it here without having worked with it.

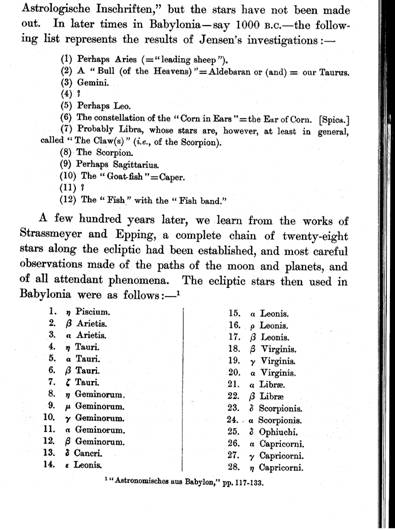

Similarly this star list will certainly be useful later on:

|