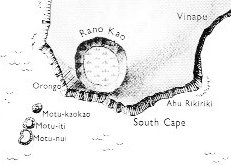

5. When Sun is absent on Easter Island (far away across the ocean and living with his winter maid) it is as if his head had been buried down in the earth, and at this point of our journey around the world we need another story from Manuscript E. It begins with the death of the Sun King: The king arose from his sleeping mat and said to all the people: 'Let us go to Orongo so that I can announce my death!' The king climbed on the rock and gazed in the direction of Hiva, the direction in which he had travelled (across the ocean). The king said: 'Here I am and I am speaking for the last time.'

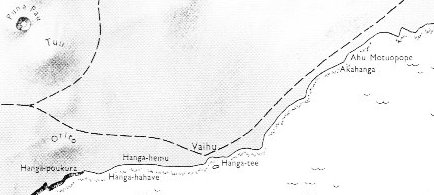

The people (mahingo) listened as he spoke. The king called out to his guardian spirits (akuaku), Kuihi and Kuaha, in a loud voice: 'Let the voice of the rooster of Ariana crow softly. The stem with many roots (i.e., the king) is entering!' The king fell down, and Hotu A Matua died. Then all the people began to lament with loud voices. The royal child, Tuu Maheke, picked up the litter and lifted (the dead) unto it. Tuu Maheke put his hand to the right side of the litter, and together the four children of Matua picked up the litter and carried it. He and his people formed a line and went to Akahanga to bury (the dead) in Hare O Ava. For when he was still in full possession of his vital forces, A Matua had instructed Tuu Maheke, the royal child, that he wished to be buried in Hare O Ava. They picked him up, went on their way, and came to Akahanga.

They buried him in Hare O Ava. They dug a grave, dug it very deep, and lined it with stones (he paenga). When that was done, they lowered the dead into the grave. Tuu Maheke took it upon himself to cover the area where the head lay. Tuu Maheke said, 'Don't cover the head with coarse soil (oone hiohio)'. They finished the burial and sat down. Night came, midnight came, and Tuu Maheke said to his brother, the last-born: 'You go and sleep. It is up to me to watch over the father.' (He said) the same to the second, the third, and the last. When all had left, when all the brothers were asleep, Tuu Maheke came and cut off the head of Hotu A Matua. Then he covered everything with soil. He hid (the head), took it, and went up. When he was inland, he put (the head) down at Te Avaava Maea. Another day dawned, and the men saw a dense swarm of flies pour forth and spread out like a whirlwind (ure tiatia moana) until it disappeared into the sky. Tuu Maheke understood. He went up and took the head, which was already stinking in the hole in which it had been hidden. He took it and washed it with fresh water. When it was clean, he took it and hid it anew. Another day came, and again Tuu Maheke came and saw that it was completely dried out (pakapaka). He took it, went away, and washed it with fresh water until (the head) was completely clean. Then he took it and painted it yellow (he pua hai pua renga) and wound a strip of barkcloth (nua) around it. He took it and hid it in the hole of a stone that was exactly the size of the head. He put it there, closed up the stone (from the outside), and left it there. There it stayed. We should notice the formulations, such as: ... Night came, midnight came, and Tuu Maheke said to his brother, the last-born: 'You go and sleep. It is up to me to watch over the father.' (He said) the same to the second, the third, and the last. Hotu Matua had 4 sons and when Tuu Maheke (the eldest) told his brothers to go to sleep he told them in age order, first the youngest, then the second, and then the third, but then the last-born was mentioned once again. In time the order is cyclical, therefore the last-born comes after the third son (i.e. in the position of the eldest, as if jokingly hinting that the youngest child - the favourite son of Hotu Matua - should be the future king rather than Tuu Maheke). |