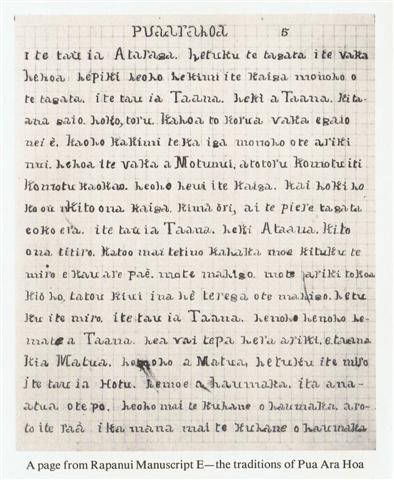

4. I believe the rongorongo signs were not meant - at least not primarily - to be letters, they were instead meant to 'document ideas', to serve as instrumental in creating beautiful rows of well ordered visual stimuli which could reflect and provoke thoughts. But myth is meant to be transmitted by mouth and to carve them onto wooden tablets cannot have been easy. Thomas Barthel's The Eighth Land. The Polynesian Discovery and Settlement of Easter Island is a book which I will rely on in the following. It is mainly based on the so called 'Manuscript E', a page of which is reproduced by Barthel:

"Pua Ara Hoa was the central figure among the korohua, a group of old Easter Islanders, who during the second decade of this century were the last living eyewitnesses of the pre-missionary era and who spent their time discussing among themselves the indigenous traditions, which had fallen into disregard among the younger Easter Islanders ... The korohua were not all lepers; sometimes healthy old men voluntarily moved to the leper station because they felt out of place in Hangaroa, where people no longer showed any interest in things of the past (TP:7). This exodus led to the unequal distribution of knowledge about the pre-missionary era among the Easter Islanders." (The Eighth Land) It must also have been difficult to commit myth to an alphabetic text, because intonation and other important signs for the ear cannot be easily translated into standardized mechanical signs for the eye. Peculiarities in the quoted text above could be due to efforts to compensate for this loss. The sentences end with a full stop (.) and then there is a vacant space before next sentence, as we can see for instance in the first line: I te tau ia Ataranga. hetuku te tagata i te vaka A capital letter is here used not only for the important person Ataranga but also at the very beginning of the page (but not at the beginning of a sentence). According to Barthel's 'improved' text (The Eighth Land, pp. 305-306) this line becomes: I te tau i a Ataranga.he tuku te tagata i te vaka I do not understand why Barthel has systematically eliminated the spaces between a full stop and the following sentence. Furthermore, breaking ia into two pieces seems to be a bit of pedantery which hardly is necessary, the meaning should be understood anyhow. The risk of destroying a pun or some other intended effect should not be underestimated. Even more so should Barthel have avoided molesting hetuku into he tuku. I cannot find any translation of this part of Manuscript E in his book, but tuku means 'to slacken, let go, to settle down' etc which is something quite different from hetu'u (star, planet) - as e.g. in Tehetu'upu (the name of a month). Nonetheless, I must rely on Barthel's translations of Manuscript E in his The Eighth Land. To acquire a photocopy of Manuscript E and then to embark on a new translation is out of the question, it would take too much effort and time. |