4. One of the basic criteria for life is eating (in whatever form it takes). To open the mouth is to encourage the forces of life. It resembles how light is returning when the sky roof opens up (like a mouth) in spring. In my glyph type dictionary I have a page which is useful for understanding the connection between life and light:

At winter solstice in ancient Egypt there was furthermore an Opening of the Way, an idea which I connect with the return of light (and life) after the temporary immobility (death) at solstice: ... Instead of that old, dark, terrible drama of the king's death, which had formerly been played to the hilt, the audience now watched a solemn symbolic mime, the Sed festival, in which the king renewed his pharaonic warrant without submitting to the personal inconvenience of a literal death. The rite was celebrated, some authorities believe, according to a cycle of thirty years, regardless of the dating of the reigns; others have it, however, that the only scheduling factor was the king's own desire and command. Either way, the real hero of the great occasion was no longer the timeless Pharaoh (capital P), who puts on pharaohs, like clothes, and puts them off, but the living garment of flesh and bone, this particular pharaoh So-and-so, who, instead of giving himself to the part, now had found a way to keep the part to himself. And this he did simply by stepping the mythological image down one degree. Instead of Pharaoh changing pharaohs, it was the pharaoh who changed costumes. The season of year for this royal ballet was the same as that proper to a coronation; the first five days of the first month of the 'Season of Coming Forth', when the hillocks and fields, following the inundation of the Nile, were again emerging from the waters. For the seasonal cycle, throughout the ancient world, was the foremost sign of rebirth following death, and in Egypt the chronometer of this cycle was the annual flooding of the Nile. Numerous festival edifices were constructed, incensed, and consecrated; a throne hall wherein the king should sit while approached in obeisance by the gods and their priesthoods (who in a crueler time would have been the registrars of his death); a large court for the presentation of mimes, processions, and other such visual events; and finally a palace-chapel into which the god-king would retire for his changes of costume. Five days of illumination, called the 'Lighting of the Flame' (which in the earlier reading of this miracle play would have followed the quenching of the fires on the dark night of the moon when the king was ritually slain), preceded the five days of the festival itself; and then the solemn occasion (ad majorem dei gloriam) commenced. The opening rites were under the patronage of Hathor. The king, wearing the belt with her four faces and the tail of her mighty bull, moved in numerious processions, preceded by his four standards, from one temple to the next, presenting favors (not offerings) to the gods. Whereafter the priesthoods arrived in homage before his throne, bearing the symbols of their gods. More processions followed, during which, the king moved about - as Professor Frankfort states in his account - 'like the shuttle in a great loom' to re-create the fabric of his domain, into which the cosmic powers represented by the gods, no less than the people of the land, were to be woven ..." ... The king, wearing now a short, stiff archaic mantle, walks in a grave and stately manner to the sanctuary of the wolf-god Upwaut, the 'Opener of the Way', where he anoints the sacred standard and, preceded by this, marches to the palace chapel, into which he disappears. A period of time elapses during which the pharaoh is no longer manifest. When he reappears he is clothed as in the Narmer palette, wearing the kilt with Hathor belt and bull's tail attatched. In his right hand he holds the flail scepter and in his left, instead of the usual crook of the Good Shepherd, an object resembling a small scroll, called the Will, the House Document, or Secret of the Two Partners, which he exhibits in triumph, proclaiming to all in attendance that it was given him by his dead father Osiris, in the presence of the earth-god Geb. 'I have run', he cries, 'holding the Secret of the Two Partners, the Will that my father has given me before Geb. I have passed through the land and touched the four sides of it. I traverse it as I desire.' ... (Cfr at A Common Sign Language.) Ancient Egypt also had a kind of a 'Scapegoat' in the form of a man who was chosen as a stand-in for the King - who thereby managed to escape death which was due: ... 'In Upper Egypt', wrote Sir James G. Frazer in The Golden Bough, citing the observations of a German nineteenth-century voyager, 'on the first day of the solar year by Coptic reckoning, that is, on the tenth of September, when the Nile has generally reached its highest point, the regular government is suspended for three days and every town chooses its own ruler. This temporary lord wears a sort of tall fool's cap and a long flaxen beard, and is enveloped in a strange mantle. With a wand of office in his hand and attended by men disguised as scribes, executioners, and so forth, he proceeds to the Governor's house. The latter allows himself to be deposed; and the mock king, mounting the throne, holds a tribunal, to the decisions of which even the governor and his officials must bow. After three days the mock king is committed to the flames, and from its ashes the Fellah creeps forth ... (Cfr at Botein.) There are 265 glyphs from Ga7-21 to Gb8-14:

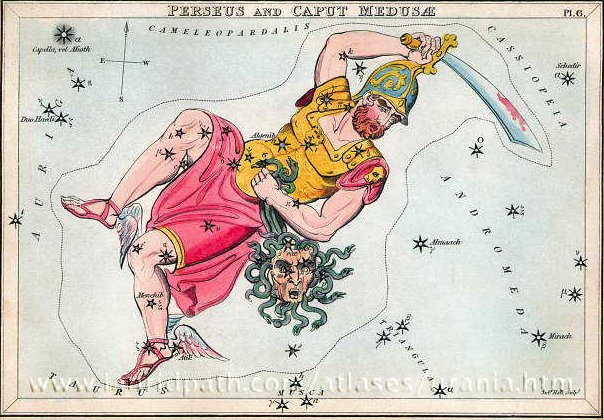

But the right ascension distance from Denebakrab to Botein is only 365.25 + 46.9 - 254.7 = ca 157 days. 265 - 157 = 108. There seems to be 472 - 364 = 108 extracalendrical nights somewhere between Ga7-21 and Gb8-13. On Hawaii (cfr at Rogo) the god Lono was playing the role as sacrifice (although there were also human sacrifices). And the King had a stand-in, 'Death-is-Near' (Koke-na-make): ... in the ceremonial course of the coming year, the king is symbolically transposed toward the Lono pole of Hawaiian divinity ... It need only be noticed that the renewal of kingship at the climax of the Makahiki coincides with the rebirth of nature. For in the ideal ritual calendar, the kali'i battle follows the autumnal appearance of the Pleiades, by thirty-three days - thus precisely, in the late eighteenth century, 21 December, the winter solstice. The king returns to power with the sun. Whereas, over the next two days, Lono plays the part of the sacrifice. The Makahiki effigy is dismantled and hidden away in a rite watched over by the king's 'living god', Kahoali'i or 'The-Companion-of-the-King', the one who is also known as 'Death-is-Near' (Koke-na-make). Close kinsman of the king as his ceremonial double, Kahoali'i swallows the eye of the victim in ceremonies of human sacrifice ... The 'living god', moreover, passes the night prior to the dismemberment of Lono in a temporary house called 'the net house of Kahoali'i', set up before the temple structure where the image sleeps. In the myth pertinent to these rites, the trickster hero - whose father has the same name (Kuuka'ohi'alaki) as the Kuu-image of the temple - uses a certain 'net of Maoloha' to encircle a house, entrapping the goddess Haumea; whereas, Haumea (or Papa) is also a version of La'ila'i, the archetypal fertile woman, and the net used to entangle her had belonged to one Makali'i, 'Pleiades'. Just so, the succeeding Makahiki ceremony, following upon the putting away of the god, is called 'the net of Maoloha', and represents the gains in fertility accruing to the people from the victory over Lono. A large, loose-mesh net, filled with all kinds of food, is shaken at a priest's command. Fallen to earth, and to man's lot, the food is the augury of the coming year. The fertility of nature thus taken by humanity, a tribute-canoe of offerings to Lono is set adrift for Kahiki, homeland of the gods. The New Year draws to a close. At the next full moon, a man (a tabu transgressor) will be caught by Kahoali'i and sacrificed. Soon after the houses and standing images of the temple will be rebuilt: consecrated - with more human sacrifices - to the rites of Kuu and the projects of the king ... When Perseus severed the head of Medusa from her body it evidently was the sacrifice needed to 'kill winter':

|