2. Knowledge of wordplays is necessary if we wish to acquire the capacity to read rongorongo texts in full, and at least some of the glyphs are to be read in rebus fashion. For instance, in our primary text example it is quite possible that the first of the glyphs is to be read X-rua (where X is an unknown word so far):

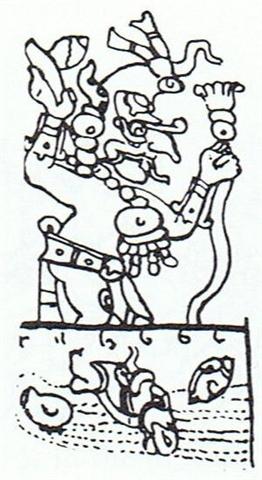

Earlier we would not have been able to realize why number 2 and a cave could have anything in common, but now we will remember the 'cave' down in the earth into which the Rain God suddenly dropped (like 'spittle') from the top of his 'tree':

Beyond midsummer comes the rain clouds and it is as if Sun suddenly had disappeared from the sky, not much different from what happens in the evening when Sun goes down as if 'swallowed by earth' at the horizon in the west. Moon rules in the night and also beyond midsummer. Beyond the 'earth cave' comes the 'sea' (naab in Yucatec) in which the Rain God is depicted as wading. And water is normally found in a hipu (a dry bottle gourd is functioning like a 'cave' containing sweet water - originating from the Rain God):

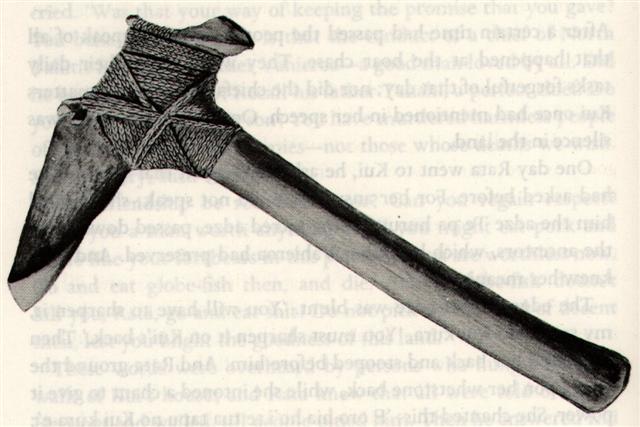

The toki sign in Eb7-2 could function like the 'hewing gesture'. It is Thursday and the Rain God has emerged from his lowest point. Thor (as in Thursday) had a magic hammer (MjŲlnir) with which he could 'hew': Never did this dreaded weapon - which was thrown - miss its mark. Afterwards it would return of its own accord to Thor's hand and, when necessary, become so small that he could easily hide it under his garments. It had a name, Mjolnir, which meant 'The Destroyer'. A magic object, the hammer Mjolnir not only served to fight the enemy but also to give solemn consecration to public or private treaties, and more especially to marriage contracts. (New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology) The stone adze (toki) of Polynesia had a similar function, and Toki was also the name of a month on Easter Island:

The adze and the hammer were signs of male power, and if we read the following account by OgotemmÍli (in Marcel Griaule's Conversations with OgotemmÍli) we will be in a better position to understand why Pani took the mallet from Hina and struck her on the head when she was beating tapa in the harbour of the gods: 'By striking the anvil,' said OgotemmÍli, 'they get back from the earth some of the life-force they gave it. Their blows recover it.' But blows on the iron must be dealt by day. The smith's work is day labour, no doubt because the smithy fire, being a fragment of the sun, could not shine at night. That is why it is forbidden, not only for smiths but for everybody, to strike blows on iron or stone or earth in the night-time. No blow of hammer or tap of pestle should be heard, whether loud or soft, in the silent hours. To strike blows at night would destroy the effect of the blows struck by day. It would mean the rejection of all that had been gained, so that the smith would lose whatever he had recovered during the day of the life-force of which he formerly divested himself. Thus the ua sign covering the head of Rogo in Eb7-1 evidently says 2 (rua). There are normally 3 'waves' in ua, and, furthermore, such glyphs are oriented vertically and not horizontally as in Eb7-1. We have therefore here an example of a Sign, to be observed and to be contemplated:

Alredy earlier I have suggested Rogo in Eb7-1 is at summer solstice instead of in his normal postition just after winter solstice. Evidence from the Rain God sequence supports this idea, and it should be the time immediately after Sun has 'plunged down into the sea', and it should be the beginning of the 2nd (rua) 'year'. It is dark down there and Rogo is enveloped by water (as if he was in a cave, rua). But he is saved by a hipu, which is protecting his sweet water (vai) from being contaminated by the salty water of the sea (tai). |