1. In front (in the face) of the normal hau tea glyph there is an 'eye' (mata), wich I associated with a sign of the rising Sun. The following dictionary page is rather speculative:

At 'zenith' not only were new houses occupied but there was also surfing on the sea. At the point of turning around from rising to descending the orientation must at some place be horizontal. Neither the horizon of rising in the east nor the horizon of descending in the west dominates. Time is horizontal like the sea. At that time, instead of the single morning Sun mata in front a suitable sign could be the Janus variant of hau tea:

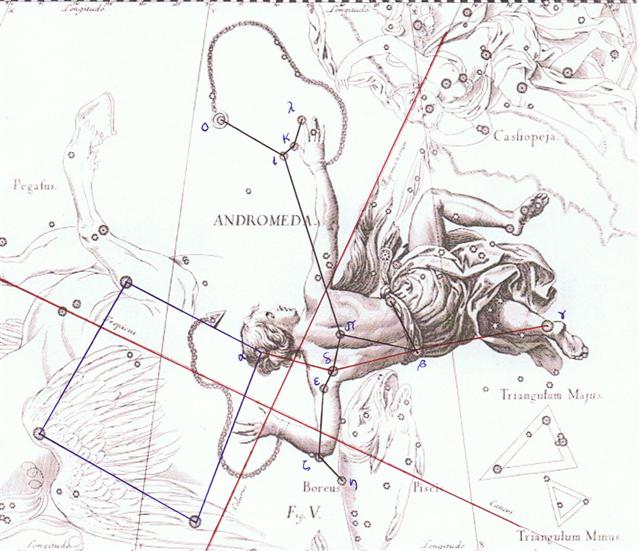

A solstice is where the luminary in the sky 'is born' (will start his voyage up) or 'dies' (will begin his descent). Thus also an equinox (a balanced state) can be considered as 'horizontal', a midstation where 'birth' and 'death' are equally far away. Mirach is β Andromedae, located in her lap according to Urania's Mirror and thus evidently signifying 'female' ('horizontal'). But according to Hevelius the star marks her girdle, the band between the upper and lower parts of her body:

Possibly the difference in position is due to the perspective. Hevelius is showing the back side of the constellations, using a 'female' perspective. At the equator of the earth the winds are indeterminate and when sailing the seas this part should be avoided. Once, when I tried to learn the Maori language, I noticed the words ngira (needle) and ngaru (wave of the sea). If there was some wordplay involved, then the sharp point could be contrasted with the billows. The morning Sun boy does not have his finger in his mouth, instead he is pointing at his closed mouth:

Points are male and billows are female. The arrival of manu tara on Easter Island announced the arrival of spring.

The solutions to many of our problems lie in the words. For instance is 'firmanent' in harmony with 'permanent'. ... In Mexican cosmology the sky fell down as the result of a prolonged rainy spell. Two gods changed themselves into trees with which it was then supported. Rain also caused the collapse of the sky in a story told by the Kato of the northwestern United States. Naga-itcho, Great Traveler, saw that the old sky which was made of sandstone and badly cracked in places was about to fall, so he and Thunder constructed a new sky. They supported it on pillars with openings at the cardinal points for clouds, winds, and mist to pass through and laid out winter and summer trails for the Sun to follow. Then it rained for many days and the old sky fell as they had anticipated. Water covered everything on the earth. When the rains ceased Naga-itcho and Thunder raised the new sky and set it in place. 'It was very dark', the curious myth continues. 'Then it was that this new earth with its long horns got up and walked down from the north'. With Naga-itcho riding on its head, it traveled far south and settled down in the place where it now lies, surrounded by the Great Waters ... The American Indian myths, anthropologists have suggested, symbolize man's early efforts at house building. The evolution from pit houses to terraced pueblos still seen in the Southwest is indeed an achievement worthy of commemoration. Among the tropical Polynesians house building was a fairly simple problem and architecture reached its highest development in New Zealand where materials were abundant and the climate necessitated structures capable of excluding the winter cold. The myth in question must have originated in the remote past and was brought from the Asiatic mainland where somewhat greater extremes of temperature marked the progress of the year. Tu the Sky-propper used arrowroot trees to support the sky after it had collapsed. So, too, men learned by trial and error how to plant posts firmly enough in the ground to support the rafters on which the roof rested. It could not have been easy to make a stable structure which would withstand wind and rain, and doubtless many a roof collapsed which its builder had considered rather a neat job. Consequently, as primitive man strove to hew out posts and rafters with half-shaped stone axes and to fasten them together in some manner so that they would carry the weight of the thatched roof and not blow down in the first hard wind, he must often have looked up at the sky and marveled that it stood so firm through tempest and hurricane and have speculated as to how it was ever raised so high above trees and mountain tops in the first place. As his repeated efforts to keep a shelter over the heads of his wife and children, as well as his own, ended in disaster, perhaps he consoled himself with the thought that even the gods must have suffered many failures before they finally succeeded in making the sky stay up there where it belonged ... |