I

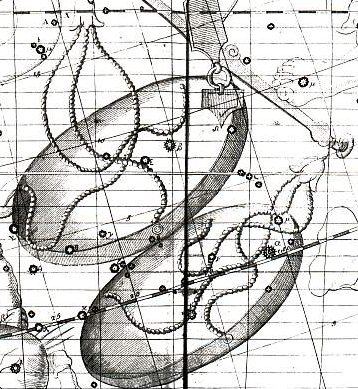

think Hevelius saw

the imbalance caused

by abandoning

Thuban, by breaking

the golden spirit

level connecting the

equinoxes:

... The dream soul

went on. She was

careless (?) and

broke the kohe

plant with her feet.

She named the place

'Hatinga Te Koe A

Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The

dream soul went on

and came to Roto

Ire Are. She

gave the name 'Roto

Ire Are A Hau Maka O

Hiva'. The dream

soul went on and

came to Tama.

She named the place

'Tama', an

evil fish (he ika

kino) with a

very long nose (he

ihu roroa) ...

Instead of a pair of

equal halfspheres

covering 12h, one

for winter time and

one for the summer,

a single-minded time

of disorder began to

form the western

civilization - no

longer was there any

veneration for the

old, instead an

exclusive adoration

of what was young

and new:

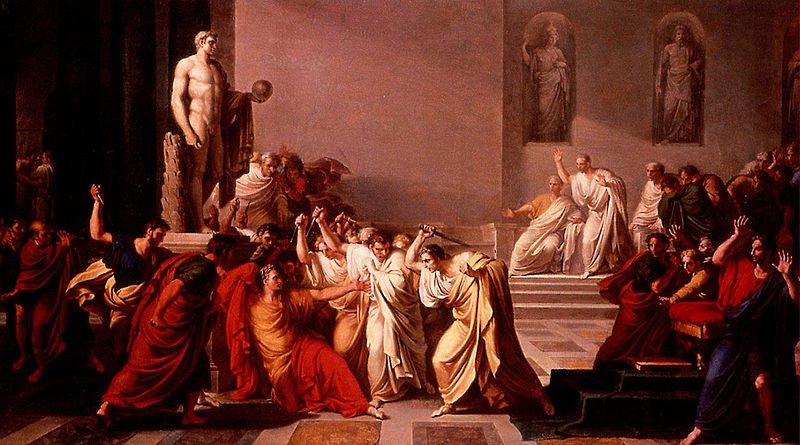

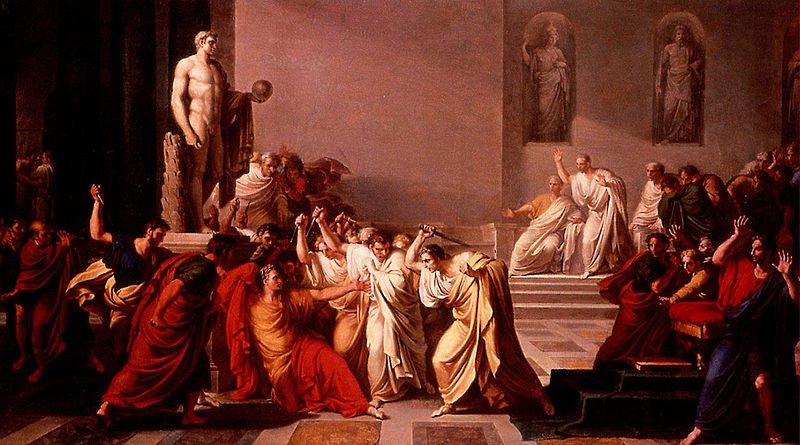

"The

Romans claimed that

it was added by them

to the original

eleven signs, which

is doubtless correct

in so far as they

were concerned in

its modern revival

as a distinct

constellation, for

it first appears as

Libra in classical

times in the Julian

calendar¹

which Caesar as

pontifex maximus

took upon himself to

form, 46 B.C., aided

by Flavius, the

Roman scribe, and

Sosigenes, the

astronomer from

Alexandria.

¹ The much-vaunted

Julian calendar was

substantially the

same in its method

of intercalation as

that formed 238 B.C.

under Ptolemy III

(Euergetes), - a

fact discovered by

Lepsius, in 1866,

when he found the

Decree of Canopus

at Sanor Tanis.

Some have associated

Andrew Marvell's

line,

Outshining Virgo or

the Julian star,

with Libra, but this

unquestionably

referred to the

comet of 43 B.C.

that appeared soon

after, and, as

Augustus asserted,

in consequence of,

Caesar's

assassination in

September of that

year, being utilized

by the emperor and

Caesar's friends to

carry his soul to

heaven." (Allen)

I had to look up in

Wikipedia to see if

the assassination

was in September or

in March (which

Henrikson had

stated). It was in

March 15 in the year

44 B.C. Why then did

Augustus suggested

September was the

month? I guess the

reason was that

September was at the

Full Moon when

spring equinox was

in March. In a way

it was the same time

as March,

and Moon was the

time giver rather

than the Sun.

March equinox

around 76 B.C. could

have been the time

when the 'twins'

Thuban and Alrisha

were abandoned,

forced to by

the precession:

|

'Equinox

around 76

B.C. |

'March 22

(81) |

23 (448) |

|

'September

20 |

21 (264) |

'Equinox |

|

April 17

(107) |

18 |

19 (475) |

|

October 17

(290) |

18 |

19 |

|

|

|

|

Cb1-1 (393) |

Cb1-2 |

Cb1-3 |

|

E tupu -

ki roto |

o te hau

tea |

|

Al

Sharatain-1

/

Ashvini-1 /

Bond-16 |

ι Arietis

(28.0), λ

Arietis

(28.2) |

ALRISHA,

χ Phoenicis

(29.2),

Alamak

(29.7) |

|

Segin,

Mesarthim,

ψ Phoenicis

(27.2),

SHERATAN,

φ Phoenicis

(27.4) |

|

Muphrid

(210.1), ζ

Centauri

(210.3) |

φ Centauri

(211.0), υ¹

Centauri

(211.1), υ²

Centauri

(211.8), τ

Virginis

(211.9) |

Agena

(212.1), θ

Apodis

(212.5),

THUBAN

(212.8) |

From

that time the twin

stars Al Sharatain

were at the northern

spring equinox, and

probably this was

primarily due to the

force of the

preceding Polaris at

the opposite side of

the sky compared to

Thuban, the old star

at the pole. Alrisha,

the Knot

in Aries, had to be

abandoned at the

same time as Thuban,

because the First

Point in Aries had

become

more accurate.

The Polynesians were

hardly impressed by

the Sun as time

giver - he

did not have 'the

necessary stability':

… Mâ-û-i was

also a prophet; he

told the people that

there would come a

vaa ama ore [=

va'a ama 'ore =

vaka ama kore]

(canoe without an

outrigger) after

which would also

come a vaa taura

ore (canoe

without cordage),

which predictions

from prehistoric

times the priests

and bards faithfully

handed to their

people, always

puzzled to

understand how such

things could be,

until the arrival of

Captain Wallis,

whose ship had also

later been described

before it appeared

as the vaa ama

ore by more

modern

prophets. Those went

still further and

also described the

foreigners who would

bring it, and in due

time came before the

astonished people

the steamship

propelled without

rigging, and the

steam tug,

literally, without

cordage... (Teuira

Henry, Ancient

Tahiti.)

... At Opoa,

at one of the last

great gatherings of

the Hau-pahu-nui,

for idolatrous

worship, before the

arrival of European

ships, a strange

thing happened

during our [the two

priests of

Porapora,

Auna-iti and

Vai-au] solemn

festivity. Just at

the close of the

pa'i-atua

ceremony, there came

a whirlwind which

plucked off the head

of a tall spreading

tamanu tree,

named

Paruru-mata'i-i-'a'ana

(Screen-from-wind-of-aggravating-crime),

leaving the bare

trunk standing. This

was very remarkable,

as tamanu

wood is very hard

and close-grained.

Awe struck the

hearts of all

present. The

representatives of

each people looked

at those of the

other in silence for

some time, until at

last a priest of

Opoa named

Vaità

(Smitten-water)

exclaimed, - E

homa, eaha ta 'outou

e feruri nei?

(Friends, upon what

are you meditating?)

- Te feruri nei i te

tapa'o o teie ra'au

i motu nei; a'ita te

ra'au nei i motu mai

te po au'iu'i mai.

(We are wondering

what the breaking of

this tree may be

ominous of; such a

thing has not

happened to our

trees from the

remotest age), the

people replied. Then

Vaità feeling

inspired proceeded

to tell the meaning

of this strange

event… I see before

me the meaning of

this strange event!

There are coming the

glorious children of

the Trunk (God), who

will see these trees

here, in

Taputapuatea. In

person, they differ

from us, yet they

are the same as we,

from the Trunk, and

they will possess

this land. There

will be an end to

our present customs,

and the sacred birds

of sea and land will

come to mourn over

what this tree that

is severed teaches.

This unexpected

speech amazed the

people and sages,

and we enquired

where such people

were to be found.

Te haere mai nei na

ni'a i te ho'e pahi

ama 'ore. (They

are coming on a ship

without an

outrigger), was

Vaitàs reply.

Then in order to

illustrate the

subject, Vaità,

seeing a large

umete (wooden

trough) at hand,

asked the king to

send some men with

it and place it

balanced with stones

in the sea, which

was quickly done,

and there the

umete sat upon

the waves with no

signs of upsetting

amid the applauding

shouts of the

people. (Teuira

Henry, Ancient

Tahiti.)

The

beginning of the

time of the severed

tree was probably

understood as such

also among the

learned men of

Europe:

|

... The

seventh

tree is

the oak,

the tree

of Zeus,

Juppiter,

Hercules,

The

Dagda

(the

chief of

the

elder

Irish

gods),

Thor,

and all

the

other

Thundergods,

Jehovah

in so

far as

he was

'El',

and

Allah.

The

royalty

of the

oak-tree

needs no

enlarging

upon:

most

people

are

familiar

with the

argument

of Sir

James

Frazer's

Golden

Bough,

which

concerns

the

human

sacrifice

of the

oak-king

of Nemi

on

Midsummer

Day. The

fuel of

the

midsummer

fires is

always

oak, the

fire of

Vesta at

Rome was

fed with

oak, and

the

need-fire

is

always

kindled

in an

oak-log.

When

Gwion

writes

in the

Câd

Goddeu,

'Stout

Guardian

of the

door,

His name

in every

tongue',

he is

saying

that

doors

are

customarily

made of

oak as

the

strongest

and

toughest

wood and

that

'Duir',

the

Beth-Luis-Nion

name for

'Oak',

means

'door'

in many

European

languages

including

Old

Goidelic

dorus,

Latin

foris,

Greek

thura,

and

German

tür,

all

derived

from the

Sanskrit

Dwr,

and that

Daleth,

the

Hebrew

letter

D, means

'Door' -

the 'l'

being

originally

an 'r'.

Midsummer

is the

flowering

season

of the

oak,

which is

the tree

of

endurance

and

triumph,

and like

the ash

is said

to

'court

the

lightning

flash'.

Its

roots

are

believed

to

extend

as deep

underground

as its

branches

rise in

the air

- Virgil

mentions

this -

which

makes it

emblematic

of a god

whose

law runs

both in

Heaven

and in

the

Underworld

... The

month,

which

takes

its name

from

Juppiter

the

oak-god,

begins

on June

10th and

ends of

July

7th.

Midway

comes

St.

John's

Day,

June

24th,

the day

on which

the

oak-king

was

sacrificially

burned

alive.

The

Celtic

year was

divided

into two

halves

with the

second

half

beginning

in July,

apparently

after a

seven-day

wake, or

funeral

feast,

in the

oak-king's

honour.

Sir

James

Frazer,

like

Gwion,

has

pointed

out the

similarity

of

'door'

words in

all

Indo-European

languages

and

shown

Janus to

be a

'stout

guardian

of the

door'

with his

head

pointing

in both

directions.

As

usual,

however,

he does

not

press

his

argument

far

enough.

Duir as

the god

of the

oak

month

looks

both

ways

because

his post

is at

the turn

of the

year;

which

identifies

him with

the

Oak-god

Hercules

who

became

the

door-keeper

of the

Gods

after

his

death.

He is

probably

also to

be

identified

with the

British

god Llyr

of Lludd

or Nudd,

a god of

the sea

- i.e. a

god of a

sea-faring

Bronze

Age

people -

who was

the

'father'

of

Creiddylad

(Cordelia)

an

aspect

of the

White

Goddess;

for

according

to

Geoffrey

of

Monmouth

the

grave of

Llyr at

Leicester

was in a

vault

built in

honour

of

Janus.

Geoffrey

writes:

Cordelia

obtaining

the

government

of the

Kingdom

buried

her

father

in a

certain

vault

which

she

ordered

to be

made for

him

under

the

river

Sore in

Leicester

(Leircester)

and

which

had been

built

originally

under

the

ground

in

honour

of the

god

Janus.

And here

all the

workmen

of the

city,

upon the

anniversary

solemnity

of that

festival,

used to

begin

their

yearly

labours.

Since

Llyr was

a

pre-Roman

God this

amounts

to

saying

that he

was

two-headed,

like

Janus,

and the

patron

of the

New

Year;

but the

Celtic

year

began in

the

summer,

not in

the

winter.

Geoffrey

does not

date the

mourning

festival

but it

is

likely

to have

originally

taken

place at

the end

of June

... What

I take

for a

reference

to Llyr

as Janus

occurs

in the

closing

paragraph

of

Merlin's

prophecy

to the

heathen

King

Vortigern

and his

Druids,

recorded

by

Geoffrey

of

Monmouth:

After

this

Janus

shall

never

have

priests

again.

His door

will be

shut and

remain

concealed

in

Ariadne's

crannies.

In other

words,

the

ancient

Druidic

religion

based on

the

oak-cult

will be

swept

away by

Christianity

and the

door -

the god

Llyr -

will

languish

forgotten

in the

Castle

of

Arianrhod,

the

Corona

Borealis.

This

helps us

to

understand

the

relationship

at Rome

of Janus

and the

White

Goddess

Cardea

who is

... the

Goddess

of

Hinges

who came

to Rome

from

Alba

Longa.

She was

the

hinge on

which

the year

swung -

the

ancient

Latin,

not the

Etruscan

year -

and her

importance

as such

is

recorded

in the

Latin

adjective

cardinalis

- as we

say in

English

'of

cardinal

importance

- which

was also

applied

to the

four

main

winds;

for

winds

were

considered

as under

the sole

direction

of the

Great

Goddess

until

Classical

times.

As

Cardea

she

ruled

over the

Celestial

Hinge at

the back

of the

North

Wind

around

which,

as Varro

explains

in his

De Re

Rustica,

the

mill-stone

of the

Universe

revolves.

This

conception

appears

most

plainly

in the

Norse

Edda,

where

the

giantesses

Fenja

and

Menja,

who turn

the

monstrous

mill-stone

Grotte

in the

cold

polar

night,

stand

for the

White

Goddess

in her

complementary

moods of

creation

and

destruction.

Elsewhere

in Norse

mythology

the

Goddess

is

nine-fold:

the nine

giantesses

who were

joint-mothers

of the

hero

Rig,

alias

Heimdall,

the

inventor

of the

Norse

social

system,

similarly

turned

the

cosmic

mill.

Janus

was

perhaps

not

originally

double-headed:

he may

have

borrowed

this

peculiarity

from the

Goddess

herself

who at

the

Carmentalia,

the

Carmenta

Festival

in early

January,

was

addressed

by her

celebrants

as

'Postvorta'

and

'Antevorta'

- 'she

who

looks

both

back and

forward'.

However,

a Janus

with

long

hair and

wings

appear

on an

early

stater

of

Mellos,

a Cretan

colony

at

Cilicia.

He is

identified

with the

solar

hero

Talus,

and a

bull's

head

appears

on the

same

coin. In

similar

coins of

the late

fifth

century

B.C. he

holds an

eight-rayed

disc in

his hand

and has

a spiral

of

immortality

sprouting

from his

double

head.

Here at

last I

can

complete

my

argument

about

Arianrhod's

Castle

and the

'whirling

round

without

motion

between

three

elements'.

The

sacred

oak-king

was

killed

at

midsummer

and

translated

to the

Corona

Borealis,

presided

over by

the

White

Goddess,

which

was then

just

dipping

over the

Northern

horizon.

But from

the song

ascribed

by

Apollonius

Rhodius

to

Orpheus,

we know

that the

Queen of

the

Circling

Universe,

Eurynome,

alias

Cardea,

was

identical

with

Rhea of

Crete;

thus

Rhea

lived at

the axle

of the

mill,

whirling

around

without

motion,

as well

as on

the

Galaxy.

This

suggests

that in

a later

mythological

tradition

the

sacred

king

went to

serve

her at

the

Mill,

not in

the

Castle,

for

Samson

after

his

blinding

and

enervation

turned a

mill in

Delilah's

prison-house.

Another

name for

the

Goddess

of the

Mill was

Artemis

Calliste,

or

Callisto

('Most

Beautiful'),

to whom

the

she-bear

was

sacred

in

Arcadia;

and in

Athens

at the

festival

of

Artemis

Brauronia,

a girl

of ten

years

old and

a girl

of five,

dressed

in

saffron-yellow

robes in

honour

of the

moon,

played

the part

of

sacred

bears.

The

Great

She-bear

and

Little

She-bear

are

still

the

names of

the two

constellations

that

turn the

mill

around.

In Greek

the

Great

Bear

Callisto

was also

called

Helice,

which

means

both

'that

which

turns'

and

'willow-branch'

- a

reminder

that the

willow

was

sacred

to the

same

Goddess

...

Hercules

first

appears

in

legend

as a

pastoral

sacred

king

and,

perhaps

because

shepherds

welcome

the

birth of

twin

lambs,

is a

twin

himself.

His

characteristics

and

history

can be

deduced

from a

mass of

legends,

folk-customs

and

megalithic

monuments.

He is

the

rain-maker

of his

tribe

and a

sort of

human

thunder-storm.

Legends

connect

him with

Libya

and the

Atlas

Mountains;

he may

well

have

originated

thereabouts

in

Palaeolithic

times.

The

priests

of

Egyptian

Thebes,

who

called

him

Shu,

dated

his

origin

as

'17,000

years

before

the

reign of

King

Amasis'.

He

carries

an

oak-club,

because

the oak

provides

his

beasts

and his

people

with

mast and

because

it

attracts

lightning

more

than any

other

tree.

His

symbols

are the

acorn;

the

rock-dove,

which

nests in

oaks as

well as

in

clefts

of

rocks;

the

mistletoe,

or

Loranthus;

and the

serpent.

All

these

are

sexual

emblems.

The dove

was

sacred

to the

Love-goddess

of

Greece

and

Syria;

the

serpent

was the

most

ancient

of

phallic

totem-beasts;

the

cupped

acorn

stood

for the

glans

penis

in both

Greek

and

Latin;

the

mistletoe

was an

all-heal

and its

names

viscus

(Latin)

and

ixias

(Greek)

are

connected

with

vis

and

ischus

(strength)

-

probably

because

of the

spermal

viscosity

of its

berries,

sperm

being

the

vehicle

of life.

This

Hercules

is male

leader

of all

orgiastic

rites

and has

twelve

archer

companions,

including

his

spear-armed

twin,

who is

his

tanist

or

deputy.

He

performs

an

annual

green-wood

marriage

with a

queen of

the

woods, a

sort of

Maid

Marian.

He is a

mighty

hunter

and

makes

rain,

when it

is

needed,

by

rattling

an

oak-club

thunderously

in a

hollow

oak and

stirring

a pool

with an

oak

branch -

alternatively,

by

rattling

pebbles

inside a

sacred

colocinth-gourd

or,

later,

by

rolling

black

meteoric

stones

inside a

wooden

chest -

and so

attracting

thunderstorms

by

sympathetic

magic.

The

manner

of his

death

can be

reconstructed

from a

variety

of

legends,

folk-customs

and

other

religious

survivals.

At

mid-summer,

at the

end of a

half-year

reign,

Hercules

is made

drunk

with

mead and

led into

the

middle

of a

circle

of

twelve

stones

arranged

around

an oak,

in front

of which

stands

an

altar-stone;

the oak

has been

lopped

until it

is

T-shaped.

He is

bound to

it with

willow

thongs

in the

'five-fold

bond'

which

joins

wrists,

neck,

and

ankles

together,

beaten

by his

comrades

till he

faints,

then

flayed,

blinded,

castrated,

impaled

with a

mistletoe

stake,

and

finally

hacked

into

joints

on the

altar-stone.

His

blood is

caught

in a

basin

and used

for

sprinkling

the

whole

tribe to

make

them

vigorous

and

fruitful.

The

joints

are

roasted

at twin

fires of

oak-loppings,

kindled

with

sacred

fire

preserved

from a

lightning-blasted

oak or

made by

twirling

an

alder-

or

cornel-wood

fire-drill

in an

oak log.

The

trunk is

then

uprooted

and

split

into

faggots

which

are

added to

the

flames.

The

twelve

merry-men

rush in

a wild

figure-of-eight

dance

around

the

fires,

singing

ecstatically

and

tearing

at the

flesh

with

their

teeth.

The

bloody

remains

are

burnt in

the

fire,

all

except

the

genitals

and the

head.

These

are put

into an

alder-wood

boat and

floated

down the

river to

an

islet;

though

the head

is

sometimes

cured

with

smoke

and

preserved

for

oracular

use. His

tanist

succeeds

him and

reigns

for the

remainder

of the

year,

when he

is

sacrificially

killed

by a new

Hercules

... |

The

lamentations for the

death of Great Pan

came when Polaris

had been established

as the new star at

the pole:

| 'March 15 |

16 |

17 |

18 (77) |

19 |

20 (445) |

| April 11 |

12 |

13 |

14 (104) |

15 (471) |

16 |

| October 11 |

12 (285) |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| *Ca14-24 |

*Ca14-25 |

*Ca14-26 |

*Ca14-27 |

*Ca14-28 |

*Ca14-29 (392) |

| te henua |

te honu kau |

manu kake rua |

te henua |

te honu |

te rima |

| δ Phoenicis (21.5) |

no star listed (22) |

Achernar (23.3) |

no star listed (24) |

no star listed (25) |

ANA-NIA |

| POLARIS, Baten Kaitos (26.6), Metallah (26.9) |

| no star listed (204) |

Heze (205.0) |

ε Centauri (206.3) |

no star listed (207) |

τ Bootis (208.2), BENETNASH (208.5), ν Centauri (208.7), μ Centauri, υ Bootis (208.8) |

no star listed (209) |

...

Everyone has once

read, for it comes

up many times in

literature, of that

pilot in the reign

of Tiberius, who, as

he was sailing along

in the Aegean on a

quiet evening, heard

a loud voice

announcing that

'Great Pan was

dead'.

This engaging myth

was interpreted in

two contradictory

ways. On the one

hand, it announced

the end of paganism:

Pan with his pipes,

the demon of still

sun-drenched noon,

the pagan god of

glade and pasture

and the rural idyll,

had yielded to the

supernatural. On the

other hand the myth

has been understood

as telling of the

death of Christ in

the 19th year of

Tiberius: the Son of

God who was

everything from

Alpha to Omega was

identified with

Pan = 'All'.

Here is the story,

as told by a

character in

Plutarch's On why

oracles came to fail

(419 B-E):

The father of

Aemilianus the

orator, to whom some

of you have

listened, was

Epitherses, who

lived in our town

and was my teacher

in grammar. He said

that once upon a

time in making a

voyage to Italy he

embarked on a ship

carrying freight and

many passangers. It

was already evening

when, near the

Echinades Islands,

the wind dropped and

the ship drifted

near Paxi. Almost

everybody was awake,

and a good many had

not finished theire

after-dinner wine.

Suddenly, from the

island of Paxi was

heard the voice of

someone loudly

calling Thamus, so

that all were

amazed. Thamus was

an Egyptian pilot,

not known by name to

many on board. Twice

he was called and

made no reply, but

the third time he

answered; and the

caller, raising his

voice, said, 'When

you come opposite to

Palodes, announce

that Great Pan is

dead.'

On hearing this,

all, said

Epitherses, were

astounded and

reasoned among

themselves whether

it were better to

carry out the order

or to refuse to

meddle and let the

matter go. Under the

circumstances Thamus

made up his mind

that if there should

be a breeze, he

would sail past and

keep quiet, but with

no wind and a smooth

sea about the place

he would announce

what he had heard.

So, when he came

opposite Palodes,

and there was

neither wind nor

wave, Thamus from

the stern, looking

toward the land,

said the words as he

heard them: 'Great

Pan is dead'. Even

before he had

finished there was a

great cry of

lamentation, not of

one person, but of

many, mingled with

exclamations of

amazement.

As many persons were

on the vessel, the

story was soon

spread abroad in

Rome, and Thamus was

sent for by Tiberius

Caesar. Tiberius

became so convinced

of the truth of the

story that he caused

an inquiry and

investigation to be

made about Pan; and

the scholars, who

were numerous at his

court, conjectured

that he was the son

born of Hermes and

Penelope ...'

We

should remember Metoro's words

around Cb1-6

(16) - coinciding

with number 398 (not

counting day zero)

for the cycle of

Jupiter (Father

Light), another

candidate for Great

Pan. Should we not

add 16 to heliacal

Polaris and reach

Cb1-6?

|

'March

25 |

26 (85) |

27 (452) |

rutua

- te

pahu -

rutua te

maeva

-

atua

rerorero

- atua

hiko ura

- hiko o

tea - ka

higa te

ao ko te

henua ra

ma te

hoi atua |

|

'September

24 |

25 (268) |

26 |

|

April 21

(111)

|

22 (478) |

23 |

|

October

21 |

22 (295) |

23 |

|

|

|

|

Cb1-5 |

Cb1-6

(398) |

Cb1-7 |

|

η

Arietis

(31.9) |

no star

listed

(32) |

θ

Arietis

(33.3),

Mira

(33.7) |

|

Neck-2 |

Al

Ghafr-13

/

Svāti-15

TAHUA-TAATA-METUA-TE-TUPU-MAVAE |

ι Lupi,

18

Bootis

(216.3),

Khambalia

(216.4),

υ

Virginis

(216.5),

ψ

Centauri

(216.6),

ε Apodis

(216.8) |

|

Asellus

Tertius,

κ

VIRGINIS,

14

Bootis

(214.8) |

15

Bootis

(215.2),

ARCTURUS

(215.4),

Asellus

Secundus

(215.5),

SYRMA,

λ Bootis

(215.6),

η Apodis

(215.8) |

|

'March

28 |

29 |

30 (455) |

31 (90) |

|

'September

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 (273) |

|

April 24 |

25 |

26 (116) |

27 |

|

October

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 (300) |

|

|

|

|

|

Cb1-8 |

Cb1-9 |

Cb1-10 |

Cb1-11

(403) |

|

no star

listed

(34) |

ξ

Arietis

(35.0) |

no star

listed

(36) |

no star

listed

(37) |

|

Asellus

Primus

(217.8) |

τ Lupi

(218.1),

φ

Virginis

(218.7)

Fomalhaut |

σ Lupi

(219.1),

ρ Bootis

(219.5),

Haris

(219.7) |

σ Bootis

(220.2),

η

Centauri

(220.4) |

In Cb1-16 the

nightside string

connecting left

and right has

been broken. I

correlate rutua

- te pahu -

rutua te maeva

(sound of

drums, sound of

sky roof moving) with

the 16th Mayan

drum month

Pax

(peculiarly

similar in name to the

windless Aegean island

Paxi where

suddenly could

be heard a loud

voice calling

out).

|

|

200 |

|

| 13 Mac |

14 Kankin |

15 Moan |

|

|

|

|

| 16 Pax |

17 Kayab |

18 Cumhu |

19 Vayeb |

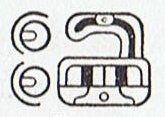

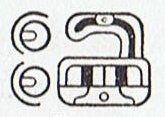

... There is a

sign, tun,

which occurs

both in 16

Pax and

19 Vayeb,

and it has been

identified as a

picture of a log

drum:

The tun

glyph was

identified as a

wooden drum by

Brinton ... and

Marshal H.

Saville

immediately

accepted it ...

[the figure

above] shows the

Aztec drum

representation

relied on by

Brinton to

demonstrate his

point. It was

not then known

that an

ancestral Mayan

word for drum

was *tun:

Yucatec

tunkul

'divine drum'

(?); Quiche

tun 'hollow

log drum';

Chorti tun

'hollow log

drum' ...

(Kelley)

The word tun

was used when

counting, for

instance

in katun

= 20 days, and

it had a glyph

of its own:

|

| tun |

The [tun]

glyph is nearly

the same as that

for the month

Pax ...

except that the

top part of the

latter is split

or divided by

two curving

lines. Brinton,

without

referring to the

Pax

glyph,

identified the

tun glyph

as the drum

called in

Yucatec pax

che (pax

'musical

instrument';

che < *te

'wooden).

Yucatec pax

means 'broken,

disappeared',

and Quiche

paxih means,

among other

things, 'split,

divide, break,

separate'. It

would seem that

the dividing

lines on the

Pax glyph

may have been

used as a

semantic/phonetic

determinative

indicating that

the drum should

be read pax,

not tun

... Thus, one

may expect that

this glyph was

used elsewhere

meaning 'to

break' and

possibly for

'medicine' (Yuc.

pax,

Tzel., Tzo.

pox).

(Kelley)

The idea of

'break' agrees

with the picture

in Cb1-6 (where

1-6 presumably

is to be read as

16, the number

of the Pax

month)

...

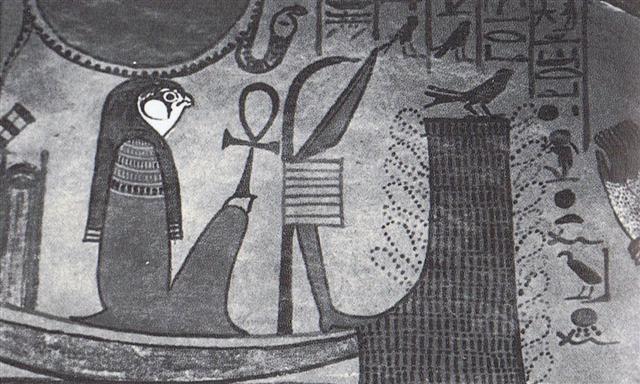

Above I have

reversed the

Mayan drum lady

to 'translate'

the time order

to our own

convention,

reading from

left to right.

We can then see

her leg at

right, in front,

but maybe there

is a 'yoke'

here, uniting

her leg with the

left leg cut

with a knife from a

butchered

Jupiter. His

right leg could

be somewhere

else, perhaps

down in

Xibalba. The

strange package

in front of

Horus - similar

to a reversed

Phoenician

kaph -

contains a leg

and above there

is a knife:

|

Egyptian

hand |

|

Phoenician

kaph |

|

Greek

kappa |

Κ

(κ) |

|

Kaph

is

thought

to

have

been

derived

from

a

pictogram

of a

hand

(in

both

modern

Arabic

and

modern

Hebrew,

kaph

means

palm/grip)

...

...

The

manik,

with

the

tzab,

or

serpent's

rattles

as

prefix,

runs

across

Madrid

tz.

22 ,

the

figures

in

the

pictures

all

holding

the

rattle;

it

runs

across

the

hunting

scenes

of

Madrid

tz.

61,

62,

and

finally

appears

in

all

four

clauses

of

tz.

175,

the

so-called

'baptism'

tzolkin.

It

seems

impossible,

with

all

this,

to

avoid

assigning

the

value

of

grasping

or

receiving.

But

in

the

final

confirmation,

we

have

the

direct

evidence

of

the

signs

for

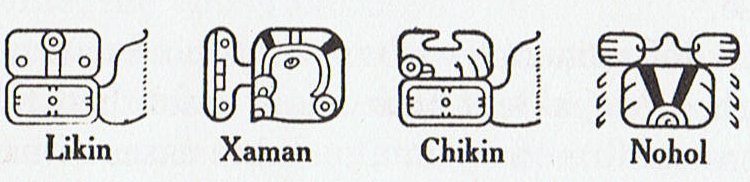

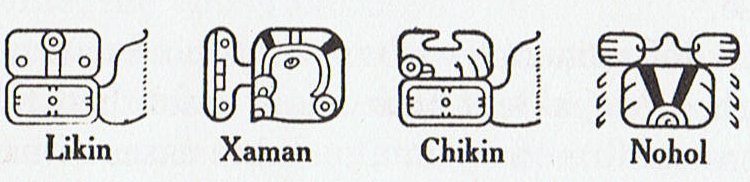

East

and

West.

For

the

East

we

have

the

glyph

Ahau-Kin,

the

Lord

Sun,

the

Lord

of

Day;

for

the

West

we

have

Manik-Kin,

exactly

corresponding

to

the

term

Chikin,

the

biting

or

eating

of

the

Sun,

seizing

it

in

the

mouth.

The

pictures

(from

Gates)

show

east,

north,

west,

and

south;

respectively

(the

lower

two

glyphs)

'Lord'

(Ahau)

and

'grasp'

(Manik).

Manik

was

the

7th

day

sign

of

the

20

and

Ahau

the

last

... |

|

32 |

no

glyph |

|

|

|

Gb7-30

(440) |

Ga1-1 |

Ga1-2

(475) |

|

η

Arietis

(31.9) |

Hyadum

II

(δ¹

Tauri)

(64.2) |

AIN,

θ¹

Tauri,

θ²

Tauri

(65.7) |

no

star

listed

(66) |

|

Asellus

Tertius,

κ

VIRGINIS,

14

Bootis

(214.8) |

In Gb7-30 -

significantly

at nakshatra

κ

Virginis

- we can see

a pair of

arms but

only a

single leg.

|

|

| vae |

haati |

| Hati

Hati 1. To break (v.t., v.i.); figuratively: he hati te pou oka, to die, of a hopu manu in the exercise of his office (en route from Motu Nui to Orongo). 2. Closing word of certain songs. Vanaga.

Hahati. 1. To break (see hati). 2. Roughly treated, broken (from physical exertion: ku hahati á te hakari) 3. To take to the sea: he hahati te vaka. Vanaga.

Ha(ha)ti. To strike, to break, to peel off bark; slip, cutting, breaking, flow, wave (aati, ati, hahati); tai hati, breakers, surf; tumu hatihati, weak in the legs; hakahati, to persuade; hatipu, slate. P Pau.: fati, to break. Mgv.: ati, hati, to break, to smash. Mq.: fati, hati, id. Ta.: fati, to rupture, to break, to conquer. Churchill. |

| Atiga Angle, corner. Mgv.: hatiga, the corner of a house; hatiga, hatihatiga, the joints or articulation of a limb. Mq.: fatina, hatika, joint, articulation, link. Ta.: fatiraa, articulation. Churchill. |

HAKI, v. Haw., also ha'i and ha'e, primary meaning to break open, separate, as the lips about to speak, to break, as a bone or other brittle thing, to break off, to stop, tear, rend, to speak, tell, bark as a dog; hahai, to break away, follow, pursue, chase; hai, a broken place, a joint; hakina, a portion, part; ha'ina, saying; hae, something torn, as a piece of kapa or cloth, a flog, ensign.Sam., fati, to break, break off; fa'i, to break off, pluck off, as a leaf, wrench off; fai, to say, speak, abuse, deride; sae, to tear off, rend; ma-sae, torn. Tah., fati, to break, break up, broken; fai, confess, reveal, deceive; faifai, to gather or pick fruit; haea, torn, rent; s. deceit, duplicity; hae-hae, tear anything, break an agreement; hahae, id. Tong., fati, break, rend. Marqu., fati, fe-fati, to break, tear, rend; fai, to tell, confess; fefai, to dispute.

The same double meaning of 'to break' and 'to say' is found in the New Zealand and other Polynesian dialects.

Malg., hai, haïk, voice, address, call.

Lat., seco, cut off, cleave, divide; securis, hatchet; segmentum, cutting, division, fragment; seculum (sc. temporis), sector, follow eagerly, chase, pursue; sequor, follow; sica, a dagger; sicilis, id., a knife; saga, sagus, a fortune-teller.

Greek, άγνυμι, break, snap, shiver, from Ѓαγ (Liddell and Scott); άγν, breakage, fragment; έκας, adv, far off, far away. Liddell and Scott consider έκας akin to έκαςτος, each, every, 'in the sense of apart, by itself', and they refer to the analysis of Curtius ... comparing Sanskrit kas, kâ, kat (quis, qua, quid), who of two, of many, &c. Doubtless έκας and έκαςτος are akin 'in the sense of apart, by itself', but that sense arises from the previous sense of separating, cutting off, breaking off, and thus more naturally connects itself with the Latin sec-o, sac-er, and that family of words and ideas, than with such a forced compound as είς and κας.

Sanskr., sach, to follow. Zend, hach, id. (Vid. Haug, 'Essay on Parsis'.) I am well aware that most, perhaps all, prominent philologists of the present time - 'whose shoe-strings I am not worthy to unlace' - refer the Latin sequor, secus, even sacer, and the Greek έπω, έπομαι, to this Sanskrit sach. Benfey even refers the Greek έκας to this sach, as explanatory of its origin and meaning.

But, under correction, and even without the Polynesian congeners, I should hold that sach, 'to follow', in order to be a relative to sacer, doubtless originally meaning 'set apart', then 'devoted, holy', and of έκας, 'far off', doubtless originally meaning something 'separated', 'cut off from, apart from', must also originally have had a meaning of 'to be separated from, apart from', and then derivatively 'to come after, to follow'.

The sense of 'to follow' implies the sense of 'to be apart from, to come after', something preceding. The links of this connection in sense are lost in Sanskrit, but still survive in the Polynesian haki, fati, and its contracted form hai, fai, hahai, as shown above. I am therefore inclined to rank the Latin sequor as a derivative of seco, 'to cut off, take off'.

Welsh, haciaw, to hack; hag, a gash, cut; segur, apart, separate; segru, to put apart; hoc, a bill-hook; hicel, id.

A.-Sax., saga, a saw; seax, knife; haccan, to cut, hack; sægan, to saw; saga, speech, story; secan, to seek.

Anc. Germ., seh, sech, a ploughshare. Perhaps the Goth. hakul, A.-Sax. hacele, a cloak, ultimately refer themselves to the Polynes. hae, a piece of cloth, a flag. Anc. Slav., sieshti (siekā), to cut; siekyra, hatchet.

Judge Andrews in his Hawaiian-English Dictionary observes the connection in Hawaiian ideas between 'speaking, declaring', and 'breaking'. The primary idea, which probably underlies both, is found in the Hawaiian 'to open, to separate, as the lips in speaking or about to speak'; and it will be observed that the same development in two directions shows itself in all the Polynesian diaclects, as well as in several of the West Aryan dialects ... (Fornander)

|

... Sorrowing, then, the two women placed Osiris's coffer on a boat, and when the goddess Isis was alone with it at sea, she opened the chest and, laying her face on the face of her brother, kissed him and wept. The myth goes on to tell of the blessed boat's arrival in the marshes of the Delta, and of how Set, one night hunting the boar by the light of the full moon, discovered the sarcophagus and tore the body into fourteen pieces, which he scattered abroad; so that, once again, the goddess had a difficult task before her. She was assisted, this time, however, by her little son Horus, who had the head of a hawk, by the son of her sister Nephtys, little Anubis, who had the head of a jackal, and by Nephtys herself, the sister-bride of their wicked brother Set. Anubis, the elder of the two boys, had been conceived one very dark night, we are told, when Osiris mistook Nephtys for Isis; so that by some it is argued that the malice of Set must have been inspired not by the public virtue and good name of the noble culture hero, but by this domestic inadventure. The younger, but true son, Horus, on the other hand, had been more fortunately conceived - according to some, when Isis lay upon her dead brother in the boat, or, according to others, as she fluttered about the palace pillar in the form of a bird.

The four bereaved and searching divinities, the two mothers and their two sons, were joined by a fifth, the moon-god Thoth (who appears sometimes in the form of an ibis-headed scribe, at other times in the form of a baboon), and together they found all of Osiris save his genital member, which had been swallowed by a fish. They tightly swathed the broken body in linen bandages, and when they performed over it the rites that thereafter were to be continued in Egypt in the ceremonial burial of kings, Isis fanned the corpse with her wings and Osiris revived, to become the ruler of the dead. He now sits majestically in the underworld, in the Hall of the Two Truths, assisted by forty-two assessors, one from each of the principal districts of Egypt; and there he judges the souls of the dead. These confess before him, and when their hearts have been weighed in a balance against a feather, receive, according to their lives, the reward of virtue and the punishment of sin.

|