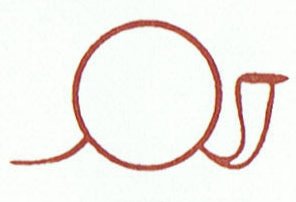

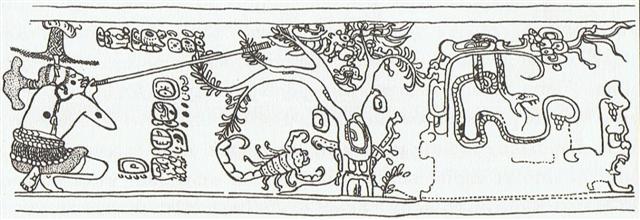

Our journey is far from simple. The ecliptic path of the Sun and the other planets was serpentine in form, with Sirius travelling together with the Sun and reaching the flattened top of the curve at midsummer - with high summer like a mountain or like the top of a tree:

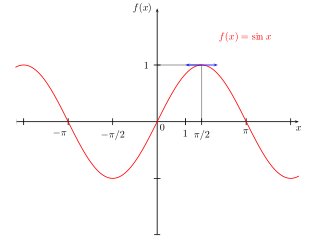

From this flat and lazy place there was a quick journey down towards the complementary pole at the very bottom, similar to how water always finds its way downwards. However, working in hard stone (the opposite of soft water) to build a durable model of this part of the journey it would not do to use the form of the flexible 'water serpent' (sinus curve). The Sun's rays are straight as arrows and water should only be perceived in the dark mirror forms of the shadows:

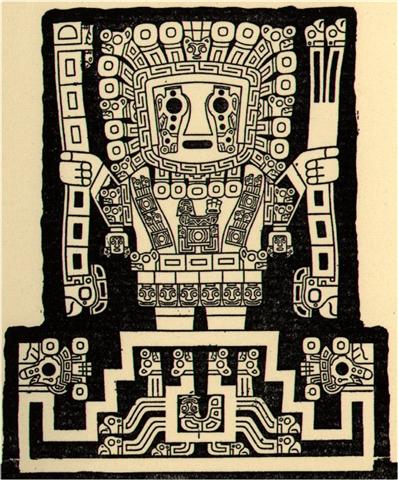

The undulating time curve over the years suggested a pair of oppositely oriented but otherwise identical 'twin mountains'. Since mankind's childhood it had been known there were, mysteriously enough, great mountains upside down which could be reached by travelling far enough south. In the southwest, where the Sun had to go down after having been turned upside down at midsummer, was the entrance to the Underworld and in this dark mirror of our own world the destiny of the Sun could have been imagined as to be standing on top of an upside down mountain with his feet immersed in its waters:

... Gilgamesh has no metaphysical temperament like the Lord Buddha. He sets out on his great voyage to find Utnapishtim the Distant, who dwells at 'the mouth of the rivers' and who can possibly tell him how to attain immortality. He arrives at the pass of the mountain Mashu ('Twins'), 'whose peaks reach as high as the banks of heaven - whose breast reaches down to the underworld - the scorpion people keep watch at its gate - those whose radiance is terrifying and whose look is death - whose frightful splendor overwhelms mountains - who at the rising and setting of the sun keep watch over the sun'. The hero is seized 'with fear and dismay', but as he pleads with them, the scorpion-men recognize his partly divine nature. They warn him that he is going to travel through a darkness no one has traveled, but open the gate for him ... These Mashu twin peaks were surely personfied and the mountain pass between them was probably that between the immortal Pollux and his twin brother Castor - the winter Beaver who built his home under water and had the finest fur of them all - and a flat tail (hiku) for splashing water (vai):

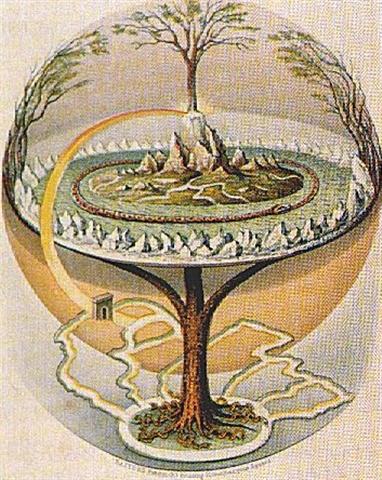

... In the deep night before the image [of Lono] is first seen, there is a Makahiki ceremony called 'splashing-water' (hi'uwai). Kepelino tells of sacred chiefs being carried to the water where the people in their finery are bathing; in the excitement created by the beauty of their attire, 'one person was attracted to another, and the result', says this convert to Catholicism, 'was by no means good' ... Though the precession had moved this 'mountain pass' away from spring equinox and the model had to be changed. The Midsummer Tree (the upright standing Milky Way) was a more durable image - although also this model was found to be unsatisfactory and the Tree had to be felled ('... the oak had made trouble right from the start'):

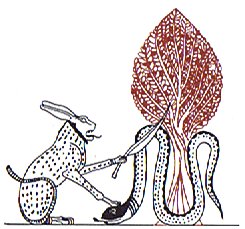

Was it Castor who used his great teeth to fell the 'Oak'? ... When (in the second rune of the Kalevala) Sämpsä Pellervoinen had sowed trees, it was the oak alone that would not grow until four or five lovely maidens from the water, and a hero from the ocean, had cleared the ground with fire and planted an acorn in the ashes; and once it had started, the growth of the tree could not be stopped: And the summit rose to heaven // And its leaves in air expanded, // In their course the clouds it hindered, // And the driving clouds impeded, // And it hid the shining sunlight, // And the gleaming of the moonlight. Then the aged Väinömoinen, // Pondered deeply and reflected, // 'Is there none to fell the oak-tree, // And o'erthrow the tree majestic? // Sad is now the life of mortals, // And for fish to swim is dismal, // Since the air is void of sunlight, // And the gleaming of the moonlight.' 'One sought above in the sky, below in the lap of the earth', as we are informed by variants, but then Väinömoinen asked his divine mother for help. Then a man arose from ocean // From the waves a hero started, // Not the hugest of the hugest, // Not the smallest of the smallest. // As a man's thumb was his stature; // Lofty as the span of woman. The 'puny man from the ocean', whose 'hair reached down to his heels, the beard to his knees', announces, 'I have come to fell the oak tree / And to splinter it to fragments'. And so he does. In several variants the oak is said to have fallen over the Northland River, so as to form the bridge into the abode of the dead. Holmberg (quoted by Lauri Honko, 'Finnen', Wb. Myth., p. 369) took the oak for the Milky Way ... There were twin 'eyes' (mata) - perhaps alluding to Castor and Pollux - who were caught like fruits up in the World Tree, with the Serpent in its shadows and visualized as 'flying like a bird' - no longer supported by the leaning sides of the 'stone (tau) mountain' but hanging from (tau) a separated 'golden bough' from which to deliver (tau) sweet rain drops ('grapes') from above:

... The jaguar learned from the grasshopper that the toad and the rabbit had stolen its fire while it was out hunting, and that they had taken it across the river. While the jaguar was weeping at this, an anteater came along, and the jaguar suggested that they should have an excretory competition. The anteater, however, appropriated the excrement containing raw meat and made the jaguar believe that its own excretions consisted entirely of ants. In order to even things out, the jaguar invited the anteater to a juggling contest, using their eyes removed from the sockets: the anteater's eyes fell back into place, but the jaguar's remained hanging at the top of a tree, and so it became blind. At the request of the anteater, the macuco bird made the jaguar new eyes out of water, and these allowed it to see in the dark. Since that time the jaguar only goes out at night. Having lost fire, it eats meat raw ...

My description above can only be a basic skeleton, but the story-trellers made it more interesting - easy to remember - by embellishing it with all sorts of amusing information. ... The Ackawois of British Guyana say that in the beginning of the world the great spirit Makonamia (or Makunaima; he is a twin-hero; the other is called Pia) created birds and beasts and set his son Sigu to rule over them. Moreover, he caused to spring from the earth a great and very wonderful tree, which bore a different kind of fruit on each of its branches, while round its trunk bananas, plantains, cassava, maize, and corn of all kinds grew in profusion; yams, too, clustered round its roots; and in short all the plants now cultivated on earth flourished in the greatest abundance on or about or under that marvellous tree.

In order to diffuse the benefits of the tree all over the world, Sigu resolved to cut it down and plant slips and seeds of it everywhere, and this he did with the help of all the beasts and birds, all except the brown monkey, who, being both lazy and mischievous, refused to assist in the great work of transplantation. So to keep him out of mischief Sigu set the animal to fetch water from the stream in a basket of open-work, calculating that the task would occupy his misdirected energies for some time to come.

In the meantime, proceeding with the labour of felling the miraculous tree, he discovered that the stump was hollow and full of water in which the fry of every sort of fresh-water fish was swimming about.

The benevolent Sigu determined to stock all the rivers and lakes on earth with the fry on so liberal a scale that every sort of fish should swarm in every water. But this generous intention was unexpectedly frustrated. For the water in the cavity, being connected with the great reservoir somewhere in the bowels of the earth, began to overflow; and to arrest the rising flood Sigu covered the stump with a closely woven basket. This had the desired effect. But unfortunately the brown monkey, tired of his fruitless task, stealthily returned, and his curiosity being aroused by the sight of the basket turned upside down, he imagined that it must conceal something good to eat. So he cautiously lifted it and peeped beneath, and out poured the flood, sweeping the monkey himself away and inundating the whole land. Gathering the rest of the animals together Sigu led them to the highest points of the country, where grew some tall coconut-palms. Up the tallest trees he caused the birds and climbing animals to ascend, and as for the animals that could not climb and were not amphibious, he shut them in a cave with a very narrow entrance, and having sealed up the mouth of it with wax he gave the animals inside a long thorn with which to pierce the wax and so ascertain when the water had subsided.

After taking these measures for the preservation of the more helpless species, he and the rest of the creatures climbed up the palm-tree and ensconced themselves among the branches.

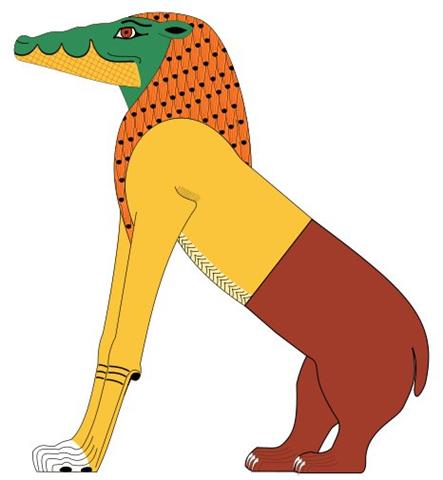

During the darkness and storm which followed, they all suffered intensely from cold and hunger; the rest bore their sufferings with stoical fortitude, but the red howling monkey uttered his anguish in such horrible yells that his throat swelled and has remained distended ever since; that, too, is the reason why to this day he has a sort of bony drum in his throat. Meanwhile Sigu from time to time let fall seeds of the palm into the water to judge of its depth by the splash. As the water sank, the interval between the dropping of the seed and the splash in the water grew longer; and at last, instead of a splash the listening Sigu heard the dull thud of the seeds striking the soft earth. Then he knew that the flood had subsided, and he and the animals prepared to descend. But the trumpeter-bird was in such a hurry to get down that he flopped straight into an ant's nest, and the hungry insects fastened on his legs and gnawed them to the bone. That is why the trumpeter-bird has still such spindle shanks. The other creatures profited by this awful example and came down the tree cautiously and safely. Sigu now rubbed two pieces of wood together to make fire, but just as he produced the first spark, he happened to look away, and the bush-turkey, mistaking the spark for a fire-fly, gobbled it up and flew off. The spark burned the greedy bird's gullet, and that is why turkey's have red wattles on their throats to this day. The alligator was standing by at the time, doing no harm to anybody, but as he was for some reason an unpopular character, all the other animals accused him of having stolen and swallowed the spark. In order to recover the spark from the jaws of the alligator Sigu tore out the animal's tongue, and that is why alligators have no tongue to speak of down to this very day ...

|