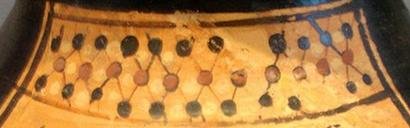

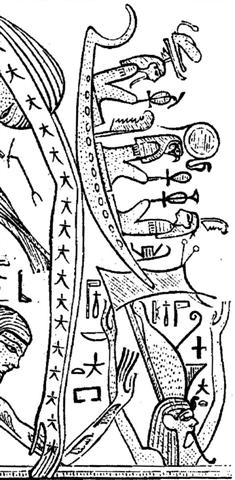

To begin at the top, with the Net:  I am convinced this 'icon' is the same as that held high (ε) by the god wearing a vertical head gear referring to Upper Egypt - in the direction leading to Abyssinia where the dark faced people lived, such as King Cepheus:  It looks as if the Pschent (double crown representing Upper and Lower Egypt) is filled with water droplets, but also the body of the god with raised up arms (in the greeting gesture) has these dots. Probably it is meant to indicate darkness. The pair of stars emerging from the top right corner of this Egyptian Net together with the similar sign leading out from the right bottom corner can be seen as contrasts, like the mathematical signs < (increasing towards right, i.e. with the right component greater than the component at left) respectively > (diminishing). From this follows that the Net itself has the position of equality (=), which sign then should be used for equinox (or dawn). At the back (bottom) side of the Net was winter (night) and in front (at the top) was high summer (daytime). I suggest the pair of stars emerging from the right upper corner of the Net could have left a pair of holes and that these could explain why the Corinthian vase has not 35 but 33 nodes in its Net (11 red and 22 dark ones). The single and exceptional blue node in the Corinthian Net could represent the prow of Pharaoh's (= the Old Solar) ship. Ships are female. Not only is this node blue, but it is descending from a 'stick' rather then from a string. Odin's 'Sun flower' has blue (cold) flames, 8 in number:

Numbers gave stability to the 'icons' in ancient times, but from the number signs the letters of the alphabets evolved and then the classical Greeks definitely destroyed the cosmos of the Bronze Age:

"What interests me most in conducting this argument is the difference that is constantly appearing between the poetic and prosaic methods of thought. The prosaic method was invented by the Greeks of the Classical age as an insurance against the swamping of reason by mythographic fancy. It has now become the only legitimate means of transmitting useful knowledge. And in England, as in most other mercantile countries, the current popular view is that 'music' and old-fashioned diction are the only characteristics of poetry, which distinguish it from prose: that every poem has, or should have, a precise single-strand prose equivalent. As a result, the poetic faculty is atrophied in every educated person who does not privately struggle to cultivate it: very much as the faculty of understanding pictures is atrophied in the Bedouin Arab. (T. E. Lawrence once showed a coloured crayon sketch of an Arab Sheikh to the Sheikh's own clansmen. They passed it from hand to hand, but the nearest guess as to what it represented came from a man who took the Sheikh's foot to be a horn of a buffalo.) And from the inability to think poetically - to resolve speech into its original images and rhythms and re-combine these on several simultaneous levels of thought into a multiple sense - derives the failure to think clearly in prose. In prose one thinks on only one level at a time, and no combination of words needs to contain more than a single sense; nevertheless the images resident in words must be securely related if the passage is to have any bite. This simple need is forgotten, what passes for simple prose nowadays is a mechanical stringing together of stereotyped word-groups, without regard for the images contained in them. The mechanical style, which began in the counting-house, has now infiltrated into the university, some of its most zombiesque instances occurring in the works of eminent scholars and divines." (Robert Graves. The White Goddess.)

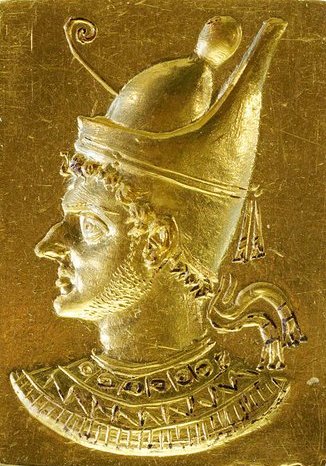

(Ptolemy VI Philometor wearing the Pschent-Double Crown, 3rd to 2nd Century BC. Ptolemaic rulers wore the Pschent in Egypt only and wore the diadem in the other territories. Wikipedia.) |