Though the glyphs say we should count not 59 nights ahead from hua poporo in Ca1-19 but instead 58 (= 2 * 29) nights:

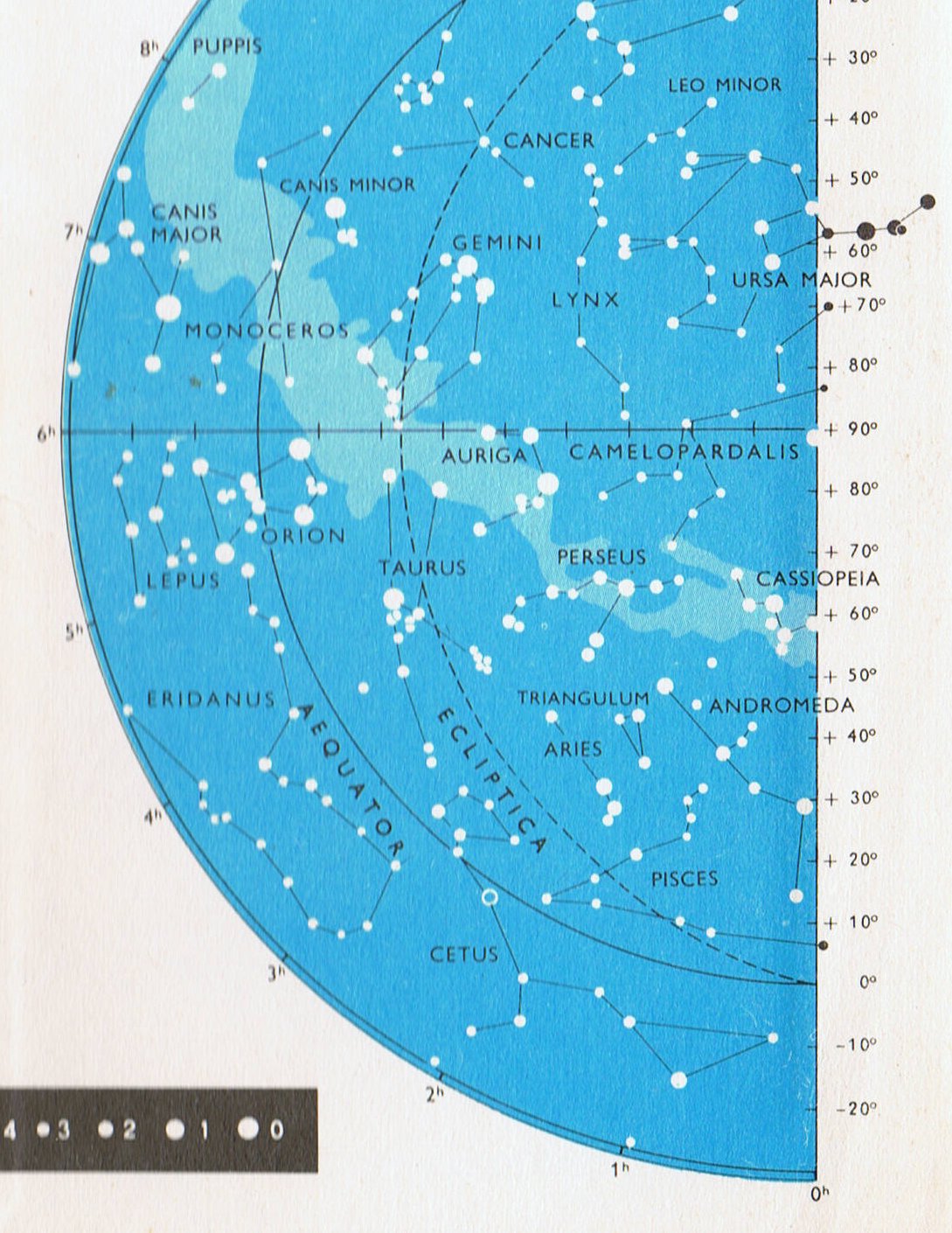

There are 4 'fruit balls' in Ca4-1, agreeing with the number of 'berries' on hua poporo. And Metoro said kua tupu te rakau. The 'fishbones' in front in Ca1-20 are 4 + 3 = 7 in number and 58 days later the number of maro 'feathers' hanging down where Rigel rose heliacally are also 7 (though ordered vertically as 3 + 4). 464 equals the last day of the year (364) + 100, and 464 + 58 = 364 + 158 = 522 = 18 * 29 (= 365 + 157). We had better document where in the text the rest of the Orion stars are. From Rigel (Ca4-2) up to and including ξ Orionis (Ca4-17) there are 16 days, but probably we should regard Betelgeuze as the last star of Orion proper. Then Orion will cover 88.3 - 78.1 = ca 10 days:

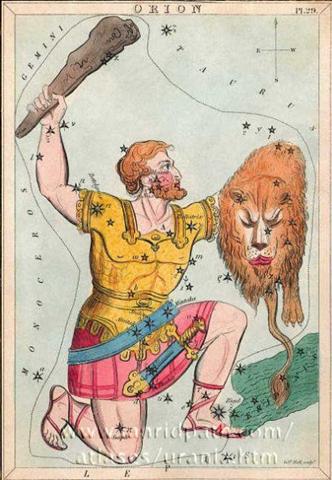

We could say Rigel is the 'nose' (menkar) of Orion - remember how Maui struck his nose to get bait - and Betelgeuze its 'tail' (deneb). There are 10 days for Orion and 10 stars within the corners defined by 'nose' and 'tail'. Probably we should disregard the 4 lesser stars which I have listed although they are down in the Milky Way (μ, χ▓, ν, and ξ). And those lesser stars which belong in today's Orion and are rising earlier than Rigel (those hidden in the Lion's hide) I have not even listed:

The Hindu system has Ardra with Betelgeuze as its station number 6:

Instead of 4 teardrops as in the Olmec corners (defining an oblong rectangle and not a diamond) there is only 1 teardrop in Ardra, probably referring to Betelgeuze as the tail of the constellation. In rongorongo times Heka (λ) rose heliacally where 3 persons (gagata is plural of tagata) are united (Ca4-7) - and maybe the hakaariki glyph refers to λ, φ╣, and φ▓ - where Mrigarshirsha (station 5) has the head of a deer. These comparatively weak stars could well motivate the idea of haka-ariki, the need to create a new king. In Olmec times the 3 Heka stars could have been the position of the head of Orion, but changing the form of the constellation from a rectangle to a diamond puts his head at the brighter Betelgeuze. However, this 'human head' is on its way down into the Milky Way river:

When in Olmec times Orion was close to spring equinox, where the sky equator and the ecliptic were crossing, it would have been natural to regard the 3 Belt stars as a mark of where this crossing station was and to see them as the midline of the Orion figure. At the other side of the sky the last star in the Scorpion's tail is Apollyon, which could be seen close to the moon when Sun was close to Betelgeuze. Apollo is the sun god. I will now complicate my description even more, because 'primitive mind' is not simple: ... Savage life is far too complex; it is only in rich civilization that we can rise to the simplicity of elemental concepts ... Either we disregard the 'savage' complications and will not understand or we have to make an effort. "... Among the Arapaho and in several other communities too, this myth, [of] which I have quoted a number of variants, is one of the foundation myths connected with the most important annual ceremony of the Plains Indians and their neighbours ... This ceremony, generally referred to as the 'Sun Dance', probably because its Dakota name means 'to stare at the sun', followed a different pattern according to the group. Nevertheless, it had a syncretic aspect, which can be explained by imitations and borrowings. In times of peace, invitations were sent out far and wide and visitors were impressed by certain rites, which they remembered and mentioned later. The number of episodes and the order in which they followed each other were not the same in all cases, but in broad outline the form of the sun-dance can be described as follows. It was the only ceremony performed by the Plains Indians in which the entire tribe took part; other ceremonies involved only particular brotherhoods of priests and certain age-grade societies. After remaining scattered during the cold season in small groups established in sheltered spots, the Indians came together in the spring for the collective hunt. At the same time as the tribe recovered its full complement of members, abundance replaced scarcity. From the sociological, as well as the economic, point of view, the beginning of summer gave the whole group the opportunity to live together again as an entity, and to celebrate its new-found unity with a great religious feast ... An observer who saw the sun-dance in the second half of the 19th century notes: 'the requirement of the Sun Dance is such that it requires every member of the tribe to be present: every clan must be present and in their place' ... So, in principle, the ceremony took place in summer. However, instances are on record when it was celebrated later in the year. The sun-dance was linked not only to the main seasonal cycles which regulated the collective life of the tribe, but also to certain incidents in the life of the individual. A member of the tribe would make a vow to celebrate the feast the following year in recognition of his escape from some danger, or because he had recovered from an illness. Preparations had to be made a long time in advance; the complicated sequence of rites had to be organized, provisions had to be collected for the feeding of the guests and gifts collected to be given to the officiants in repayment of their services. Also, the new 'owner' of the dance had to receive his title from his predecessor, and, from the priests and other qualified dignitaries, the rights attaching to the various phases of the ritual. During these transactions, he solemnly handed over his wife to the man he called his ceremonial 'grandfather', and whose 'grandson' he became, for the purposes of a real or symbolic act of copulation, which took place out of doors at night in the moonlight, and during which the grandfather transferred a piece of root, representing his semen, from his own mouth to that of the wife, who then spat it into her husband's mouth. Throughout the feast which lasted several days the officiants fasted and neither ate nor drank - the Plains Cree called the ceremony 'the-abstaining-from-water-dance' ... - and submitted to various mortifications. For instance, the penitents ran sharp wooden skewers into their dorsal muscles, and made them fast to thongs attatched to the central pole, around which they danced and leapt until the skewers were wrenched out, together with the flesh; or else they trailed behind them heavy objects, such as buffalo skulls with horns which dug into the ground. These objects were attatched to their backs in the same way, and with the same result. First, the priests and chief officiants met in a tent set up apart from the others, in order to proceed in secret with the preparation or renewal of the liturgical objects. Then, groups of warriors went to fetch the tree-trunks necessary for the erection of the framework of a huge lodge roofed over with branches. The trunk intended to serve as the central pole was hacked at and felled as if it were an enemy. It was in this public lodge that the rites, songs and dances took place. In the case of the Arapaho and the Oglala Dakota, at least, it would seem that a period of unbridled licence prevailed, and was perhaps even prescribed, on this night ... While the generic name given to this group of extremely complex ceremonies probably exaggerates their solar inspiration, the solar element should not be underestimated. In actual fact, sun-worship was ambigous and equivocal in character. On the one hand, the Indians prayed to the sun to be favourably disposed towards them, to grant long life to their children and to increase the buffalo herds. On the other hand, they provoked and defied it. One of the final rites consisted in a frenzied dance which was prolonged until after dark, in spite of the exhausted state of the participants. The Arapaho called it 'gambling against the sun', and the Gros-Ventre 'the dance against the sun'. The aim was to counteract the opposition of the intense heat of the sun, who had tried to prevent the ceremony taking place by radiating his warm rays every day during the period preceding the dance ... The Indians, then, looked upon the sun as a dual being: indispensable for human life, yet at the same time representing a threat to mankind by its heat, a presage of prolonged drought. One of the motifs of the Arapaho dancers' body-paintings shows them being 'consumed by fire' ... An informant belonging to the same tribe relates that 'in the past, during one sun-dance, it became so hot that the pledger (officiant) was unable to continue the ceremony and left the lodge. The other dancers followed, as they could not continue the dance without him' ... But the sun was not alone in being involved: the Thunder-Bird's nest was placed in the fork of the central pole. The link with thunder, and more especially with spring storms, emerges even more clearly in the mythology of the central Algonquin, according to whom the dance, referred to elsewhere as 'the sun-dance', had replaced an ancient ritual intended to hasten the arrival of the rain-storms ... In the Plains, too, the dance fulfilled a dual purpose, which was to conquer an enemy, usually the sun, and to force the Thunder-Bird to release rain. One of the foundation myths concerning the dance describes a great famine which an Indian and his wife succeeded in bringing to an end by their knowledge of the rites and the recovery of fertility ... There is, then, a very close analogy between the sun-dance, as performed by the Plains Indians, and the ceremony of the great fast, as celebrated by the SerentÚ Indians to ensure that the sun continued exactly on its course, and brought the drought to an end ... In both cases, the ceremony concerned was the major one of the tribe and involved all its adult members. The officiants neither ate nor drank for several days. The ritual was performed near a pole which represented the path to the sky. Around this pole, the Plains Indians danced and whistled in imitation of the Thunder-Bird's cry. The SerentÚ did not erect their pole until they had heard the 'whistling', arrow-bearing wasps ... In both instances, the ritual ended with the distribution of consecrated water. In the case of the SerentÚ, the water was contained in separate receptacles and could be pure or roiled (meaning 'turbid' or 'tainted'); the penitents drank the pure water but refused the other. The 'perfumed water' used in the Arapaho rite was sweet, yet it symbolized menstrual blood, a liquid not in keeping with the sacred mysteries ..." (Claude LÚvi-Strauss, The Origin of Table Manners. Introduction to a Science of Mythology: 3.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||