When the hand is turned towards the mouth, showing the gesture of eating (kai), it is normally drawn with 3 fingers visible. When the hand is empty and turned in the opposite direction also the thumb can be seen. Therefore it is possible the kai-kai sign - if such it is - in Ka3-3--4 means 'empty':

|

|

|

|

|

| Ka3-1 (*108) |

Ka3-2 |

Ka3-3 |

Ka3-4 |

Ka3-5 (46) |

| |

|

Wasat (109.8) |

Aludra, Propus (111.1) |

Gomeisa (111.6), ρ Gemini (112.1) |

| 'July 7 |

'8 |

'9 |

'10 |

'11 (192) |

| Al Tuwaibe' 12 |

13 |

Heka 1 |

2 |

3 (56) |

We know cat's cradles were not allowed when Sun was close to the horizon:

... string games could be resumed after it was clear that the Sun had managed to leave the horizon and was rapidly gaining in altitude: 'Before the sun starts to leave the horizon ... when it shows only on the horizon, ... then string games were no longer allowed as they might lacerate the sun. Once the sun had started to go higher and could be seen in its entirety, string games could be resumed, if one so wished. So the restriction on playing string games was only applicable during the period between the sun's return and its rising fully above the horizon ...

This was the rule among the Inuit peoples far up close to the pole. At the latitude of Easter Island the rule could perhaps instead have been to use kaikai strings to create a full stop for Old Sun, for the year which was completed at the solstice.

| Kaikai 1. Cat's cradle, in which patterns are made by moving a thread through the fingers of both hands, and are accompanied by the recitation of verses (one of the main pastimes of yore). 2. Sharp: also 'to sharpen' used instead of hakaka'ika'i. Vanaga.

1. Mastication, to eat heavily. 2. Sharp, cutting, edge of a sword, point of a lance; moa tara kaikai, cock with long spurs. Churchill. |

Pollux, the twin who lived on, was a pugilist. This strange piece of information must have been included in the myth because it is a Sign. In boxing no fingers are seen, and the clenched fists were once bound by leather thongs (a kind of strings). Such a fist would have looked like that in e.g. Gb6-19:

|

|

| Gb6-19 (*100) |

tagata mau |

61 * 9 = 549 = 3 * 183.

| Mau Mau. 1. Very, highly; űka keukeu mau, very hard-working girl. 2. To be plentiful; he-mau to te kaiga, the island abounds in food. 3. Properly. Ma'u. 1. To carry, to transport; he-ma'u-mai, to bring; he-ma'u-atu, to remove, ma'u tako'a, to take away with oneself; te tagata hau-ha'a i raro, ina ekó ma'u-tako'a i te hauha'a o te kaiga nei ana mate; bienes terrenales cuando muere → a rich man in this world world cannot take his earthly belongings with him when he dies. 2. To fasten, to hold something fast, to be firm; ku ma'u-á te veo, the nail holds fast. 3. To contain, to hold back; kai ma'u te tagi i roto, he could not hold his tears back. Vanaga.

1. As soon as, since. 2. Several; te mau tagata, a collective use. 3. Food, meat; mau nui, abundance of food, provision, harvest; mau ke avai, abundance. 4. End, to take away. 5. To hold, to seize, to detain, to arrest, to retain, to catch, to grasp. 6. Certain, sure, true, correct, to confide in; mau roa, indubitable, sure. 7. Fixed, constant, firm, stable, resolute, calm; tae mau, not fixed, unstable; mau no, stable; hakamau, to make firm, to attach, to consolidate, to tie, to assure; pena hakamau, bridle; hakamau ihoiho, to immortalize; hakamau iho, restoration. 8. To give, to accord, to remit, to satisfy, to deliver; to accept, to adopt, debt; to embark, to raise. Mamau. To arrest. Churchill.

OR. All. Fischer.

T. 1. Really. E ari'i mau teie vahine = this woman really is a princess. 2. Things. Te mau mautai = plenty of things. 3. Hold. A toro te a'a, a mau te one = the roots spread and held the sand. Henry. |

| "It has not been found necessary to call the numeral one after some object which is a visible unit in nature: one is not the word for nose, for an instance; nor is two the word for eyes or ears, which as pairs upon the primitive mathematician are surely as visible, tangible, obvious as the five fingers of one hand. Three is found to be independent of any such obvious concrete presentation; four also. Why, then, must five be considered a secondary sense of hand? As to our English five we might see a beautiful reasonableness in naming it from the fingers of our own mathematical hands. We stick up our fingers in reckoning; the first task of our nursemaid mathematicians at school is to teach the child that sums are no longer to be done on the fingers but on slates with pencils. Thereafter follows mental arithmetic with a new series of tortures all its own.

But in the islands of our study fingers go not up but down for the count. The hand with its digits displayed coram publico is zero, cipher, naught. It is the clenched fist which counts most, it reckons five; a usage paralleled, to be sure, in our idiom of that noble art of defending ususally most ignoble selves, 'I put my bunch of fives in his -' mug, was it? Or peeper? Or possibly breadbasket, this being before the days when solar plexus had given to the ring the dignity of astrological anatomy. The five of the clenced fist I recall from many an island race.

Let me, however, confirm my stestimony from an authority who believes that five is the hand, Dr. Codrington (Melanesian Languages 222, note 1):

The way of reckoning on the fingers differs in various islands. In Nengone the fingers are turned up and brought together at five. In the Banks Islands the fingers are turned down. This is often done with the spoken numerals, often without the use of words. The practice of turning down the fingers, contrary to our practice, deserves notice, as perhaps explaining why sometimes savages are reported to be unable to count above four. The European holds up one finger, which he counts, the native counts those that are down and says 'four'. Two fingers held up, the native counting those that are down, calls 'three'; and so on until the white man, holding up five fingers, gives the native none turned down to count. The native is nunplussed, and the enquirer reports that savages can not count above four."

William Churchill, The Polynesian Wanderings. |

When I worked with correlating Metoro's readings with the glyphs I noted the possibility of a wordplay involving kahi:

| Kahi Tuna; two sorts: kahi aveave, kahi matamata. Vanaga.

Mgv.: kahi, to run, to flow. Mq.: kahi, id. Churchill. |

There were several instances where Metoro said kai but with no sign of fingers towards a mouth. Instead there seemed to be a correlation with fishes and I concluded he might have said kai as some dialectal version of kahi.

|

| Cb4-10 |

| ka kake ki te kai |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ca5-25 |

Ca5-26 |

Ca5-27 |

Ca5-29 |

Cb2-15 |

Cb8-25 |

Cb8-29 |

| etoru kahi |

te kahi |

te kahi huga |

kua hua te kahi |

te kahi |

|

|

| kai |

kahi |

At this later stage in my investigation I think ka(h)i could have been used by Metoro in order to point out how the allusions from kai (to stop, e.g. in kaiga = place of residence) easily could be changed into the positive kahi (to flow on). At any rate I decided to define a kahi glyph type.

In its normal orientation the kahi fish is rising, but in Ka3-5 it is descending. Kaikai strings can make the flow stop (mau).

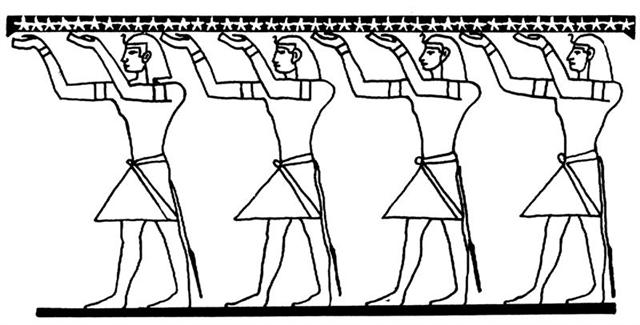

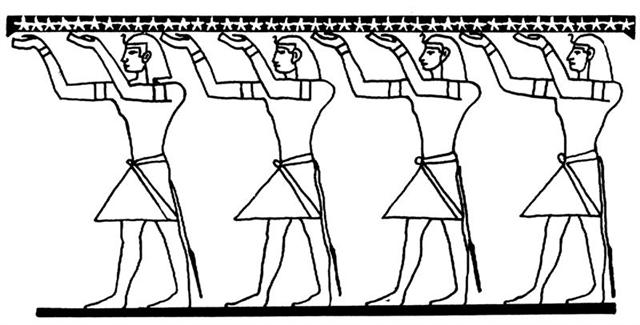

The internal sign in the kahi type of glyph is a separate entity which we can recognize as the 'star pillar' of ancient Egypt. When it is turned upside down it becomes the basic element of the Egyptian cloth sign (implying darkness):

Beyond the middle of the year when Sun has passed his apex (his 'best before' date), he must descend, and ultimately he has to disappear behind the mountains at the horizon. The beginning of the descent (hakaturu) of Sun is an event at noon, not at dusk. I have one more piece to the kahi puzzle, viz. in the Moriori islander's myth of creation: ... In the beginning were Rangi and Papa, Sky and Earth. Darkness existed. Rangi adhered over Papa his wife. Man was not. A person arose, a spirit who had no origin; his name was Rangitokona, the Heaven-propper. He went to Rangi and Papa, bid them go apart, but they would not. Therefore Rangitokona separated Rangi and Papa, he thrust the sky above. He thrust him with his pillars ten in number end to end; they reached up to the Fixed-place-of-the-Heavens. After this separation Rangi lamented for his wife: and his tears are the dew and the rain which ever fall on her.

This was the chant that did the work:

Rangitokona, prop up the heaven! // Rangitokona, prop up the morning! // The pillar stands in the empty space.

The thought [memea] stands in the earth-world - // Thought stands also in the sky.

The kahi stands in the earth-world - // Kahi stands also in the sky.

The pillar stands, the pillar - // It ever stands, the pillar of the sky.

Then for the first time was there light between the Sky and the Earth; the world existed ...

When kahi stands both in the earth-world and in the sky it ought to mean kahi is something which connects earth and sky. And kahi seems to be of the same dignity as memea. They could for instance mean lines of declination and right ascension.

"This version was collected around 1869 by the Chatham Islands sheep-farmer Alexander Shand from Hira-wanu Tapu, a true Moriori (indigenous Chatham Islander). He, however, had grown up as a slave of invading Taranaki Maoris who had commandeered a whaler and 'conquered' the islands in 1835. He only spoke Maori.

In consequence he could not put the stories down in the Moriori dialect; nor could he or anyone explain certain words in the first chant. In order to complete it I have ventured to translate 'memea' as 'thought' (its Rarotongan meaning), leaving 'kahi' unattempted." (Antony Alpers, Legends of the South Seas.)

I guess the Moriori kahi refers to the same type of central line which was drawn inside the fishes of the kahi type. In other words there could be 4 kahi corner-of-the-earth pillars:

... The Mayas called their 4 supporters of the sky Bacab:

'Among the multitude of gods worshipped by these people were four whom they called by the name Bacab. These were, they say, four brothers placed by God when he created the world at its four corners to sustain the heavens lest they fall.' (Diego De Landa according to Graham Hancock in his Fingerprints of the Gods.)

'In the ms. Ritual of the Bacabs, the cantul kuob [the suffix '-ob' indicates plural], cantul bacabob, the four gods, the four bacabs, occur constantly in the incantations, with the four colors, four directions, and their various names and offices.' (William Gates, An Outline Dictionary of Maya Glyphs.)

'... This connects up the present section with the beginning of the 'sacred tonalamatl', at the Spring equinox with the Mayas as with the Mexicans, and in the center of the 364-day year (52 days of which preceded and 52 followed the tonalamatl or tzolkin), ruled by its 91-day quarters by the Four Bacabs, whose quarternary repetition (in the 1820-day period) we have thus verified ...' (Gates, a.a.)

1820 = 20 * 91, i.e. the bacabs circulated 5 times in the 1820-day period, 5 * 364 = 1820, and 7 * 260 also happens to be 1820.

They were ruling the 4 quarters of a 364-day long year, and in the center of this year there were 260 days, the sacred tonalamatl (tzolkin) calendar, which began at spring equinox:

|

52 |

260 = 5 * 52 |

52 |

|

364 = 4 * 91 = 7 * 52 |

|

If the kahi sky supporters are 4 in number, then we could guess there should be 4 kahi fishes in the text. However the K tablet is too short to cover a whole year and instead there are only 2:

|

45 |

|

52 |

|

82 (?) |

| Ka3-5 (46) |

Kb1-7 (99) |

|

181 (?) |

|