4. From the first station (with the Golden Plover) they go inland, Fakataka and her child, and presumably she builds a house for them not far later on: ... They go inland at the land. The child nursed and tended grows up, is able to go and play. Each day he now goes off a bit further away, moving some distance away from the house, and then returns to their house. So it goes on and the child is fully grown and goes to play far away from the place where they live. He goes over to where some work is being done by a father and son. Likāvaka is the name of the father - a canoe-builder, while his son is Kuikava. With a home (house) at winter solstice - which we can presume - the boy is gradually moving away as he grows older. Each day he moves a bit further away from the pole, before he returns in the evening. His path resembles that of Sun, who gradually moves away from the point far in the south were the pole stands. When he is fully grown he encounters people who are building a canoe. The canoe means a sea-voyage lies ahead. Land stretches from winter solstice to high summer, then it turns into sea. In high summer new houses are built down on earth, and they will give shelter in the night. The night is the sea, and Sun will cross over the nightside sea in his canoe and reemerge next morning, rising at the horizon in the east. Down on earth the houses are built after the form of his canoe, to be slept in during the nights. The ruins of hare paega houses are spread out on the slopes of Rano Kau, as if they had emerged from the crater, or as if they were bound to go down there:

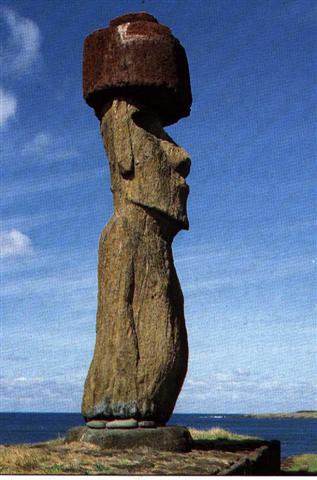

The latter alternative must be the correct one, because at the other end of the island Rano Raraku is the place where the moai statues were born (hewn out from the cliff):

They are standing up like Sun in the morning and represent the male pole (ure), in contrast to the female lying down oval of paega stones, ready to swallow Sun in the west. According to Thor Heyerdahl's Påskön, en gåta som fått svar, when the islanders were asked why there were no ure (penis) on the stone giants an old man calmly replied: 'A moai cannot have two ure, he is one himself.' As to the form of the moai statues a famous myth confirms: Métraux quotes a Rapa Nui legend in which carvers from Hotu Iti (eastern sector) journeyed to the western sector to seek the advice of a master carver. They were perplexed about how to resolve the difficult problem of carving the statue neck. He advised them to seek the answer by viewing their own bodies. They did so, and discovered that the model for the statue neck was the penis (ure). (Van Tilburg) |