1. This is still a dictionary, albeit of a peculiar kind. From our common background with the alphabet it is quite natural to expect also the rongorongo glyphs to be 'letters'. However, nothing could be more wrong. In the ancient cosmos it was the whole which gave meaning, not the dancing specks of dust in themselves. And, indeed, also we must admit that the individual (letter, pixel, number, etc) is without meaning if we cannot see the background, the surrounding context. Signs are markers against the background and they can be anything, as long as they make a contrast, an impression on us. This is a dictionary of signs and it cannot be such a dictionary if only the types of glyphs with their meanings are described. As a first step away from the major 'bricks' of the rongorongo system - the glyph types - we have now surely come to accept that they are not stamped out like the products of a machine, where each item of a certain kind is identical with all such. Instead the rule is that they never are identical with such of the same kind. Which means that when we once in a while will stumble on indentical glyphs must react to the Sign they are meant to be. For instance, the glyph type which I (with invaluable help from Metoro Tauga Ure) have labelled tagata exhibits examples in the G text which rarely are alike. Those 13 below are only a small part of the total 55 tagata glyphs of various sorts which I with great effort once distilled from G:

On side b (beyond Gb1-5) there are 8 of a lesser stature (but with taller necks) than tagata in Ga4-1, yet basically they are of the same type:

On closer examination we find 3 tagata (redmarked) which have 'feathers' on their heads, one with 3 such and the other two with just a hint. The remaining 5 are more alike, but not exactly so. The expert will immediately find an important additional sign (an adjunct) in form of a little dot. Thus, of these 5 + 8 = 13 glyphs only 4 seem to be really alike:

They are standing out against the background in being identical, and this fact is a Sign (cfr Definition of Sign). Their number is another Sign. Once number 4 gave associations to 'earth', the quadrangular structure in time which has its corners (cardinal points) at the equinoxes and the solstices. These corners define the quarters of the year, like the sides of a square - although it is a square oriented like a rhomb with midsummer at bottom. This abstract 'earth' in time-space was then closely connected in mind with our more familiar down-to-earth such, which hides half the sky dome from our view. And from here the associations could move on in several directions, e.g. the fact that living things grow up from the earth beneath our feet. In an agricultural society this is a fundamental concept, Mother Earth provides us with what we need to survive. And when we die we will return to her, to close the cycle, how else could we recycle like all other living beings. Our body once again becomes earth, but our living spirit (manu rere) moves in the opposite direction, up towards the sky like a bird or like the flames of a fire. Later it will recycle by descending to live in a suitable new body once again growing from earth. Thus number 4 should hit hard upon our consiousness, it is not an arbitrary number. In Eastern cultures it is still so: "Interestingly, since another meaning of shi is 'death', the number 4 is considered unlucky. (For example, the floor numbering in hotels sometimes jumps mysteriously from 3 to 5; it's also considered unlucky to give four of something as a present.)" (Richard Smith & Trevor Hughes Parry, Japanese. Language and People.) No number was arbitrary, they all carried meaning. By the way, the dot which is meant to draw our attention in Gb5-27 can easily be explained, we need not look at the surrounding glyphs to understand it, because there are 52 weeks in a year and a year stretches for 7 * 52 = 364 days. A basic rule as regards the conjunction of an ordinal number for a line (5) with the ordinal number in the line (27) is not to multiply 5 * 27 but to take 52 * 7, i.e. to let the last digit be a separate unit in the multiplication. This rule of thumb I discovered by experience but have not yet any satisfying explanation for. The glyph type which follows tagata with a dot I have labelled mauga (mountain):

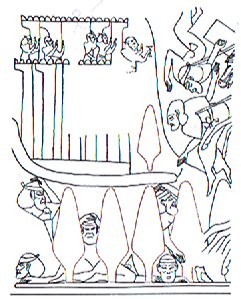

The year is longer than 364 days, around 365¼ days, and if each glyph should represent a day (which I believe is a basic rule for reading the G text) then there must have been a problem in how to describe the fraction of a day, an enemy to order. One possibility was to depict a mountain, though admittedly a strangely drawn such, it could easily be understood as a tree, behind which the light of reason goes down, like when Sun in the evening is hiding behind the mountains in the west, cfr at The Week: ... In the ancient Egyptian system of signs a similarly looking form (nehet) was used for 'tree', and it is possible to hide among trees (like Charles II did in an oak). In a relief from the Amon Temple of Karnak the Syrian enemies of Pharaoh Seti I are depicted as hiding among trees:

To see clearly you need good light. Experience from how Moon oddly draws away about each 29th night (+ a fraction) probably was the inspiration for the idea of light disappearing at the end of a cycle. When it reappeared counting could begin anew, and order had been restored, reborn. Thus, the last day of the year (number 365) could be described by a mountain - the last day of the year was like the last day of the month, obscured, cut off from the previous well ordered sequence of days. A well ordered month has 28 nights and a well ordered year has 364 days. This is one of the origins for the structure of numbers in time-space, with time counted in fortnights and not in weeks:

Yesterday I happened to watch a TV program where the strange adobe pyramids of Túcume in Peru were described. It was mentioned that they for some unknown reason were as extraordinary many as 26. We can now guess why - each such pyramid represented a fortnight.

The close connection between these 26 pyramids on one hand and the famous pyramid of Kukulkan is obvious (cfr at Vero):

... Behind me, towering almost 100 feet into the air, was a perfect ziggurat, the Temple of Kukulkan. Its four stairways had 91 steps each. Taken together with the top platform, which counted as a further step, the total was 365. This gave the number of complete days in a solar year. In addition, the geometric design and orientation of the ancient structure had been calibrated with Swiss-watch precision to achieve an objective as dramatic as it was esoteric: on the spring and autumn equinoxes, regular as clockwork, triangular patterns of light and shadow combined to create the illusion of a giant serpent undulating on the northern staircase ... The north direction is where the serpent goes down, his head is at bottom left in the picture. |