4. In Hamlet's Mill there is an important statement regarding the sea monster: "That Tiamat is the Milky Way, and no 'Great Mother' in the Freudian sense, any more than Ganga, Anahita and others, seems by now obvious." Cassopeia lies in the Milky Way and the Stag is also there. And the same goes for Cetus: "Although an old constellation, Cetus is by no means of special interest, except as possessing the south pole of the Milky Way and the Wonderful Star, the variable Mira; and from the fact that it is a condensation point of nebulae directly across the sphere from Virgo, also noted in this respect." (Allen) One more nugget from Hamlet's Mill: "A sidelight falls upon the notions connected with the stag by Horapollo's statement concerning the Egyptian writing of 'A long space of time: A Stag's horns grow out each year. A picture of them means a long space of time.' Chairemon (hieroglyph no. 15, quoted by Tzetzes) made it shorter: 'eniautos: elaphos'. Louis Keimer, stressing the absence of stags in Egypt, pointed to the Oryx (Capra Nubiana) as the appropriate 'ersatz', whose head was, indeed, used for writing the word rnp = year, eventually in 'the Lord of the Year', a well-known title of Ptah. Rare as this modus of writing the word seems to have been - the Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache (eds. Erman and Grapow), vol. 2, pp. 429-33, does not even mention this variant - it is worth considering (as in every subject dealt with by Keimer), the more so as Chairemon continues his list by offering as number 16: 'eniautos: phoinix', i.e., a different span of time, the much-discussed 'Phoenix-period' (ca. 500 years). There are numerous Egyptian words for 'the year', and the same goes for other ancient languages. Thus we propose to understand eniautos as the particular cycle beloning to the respective character under discussion: the mere word eniautos ('in itself', en heauto; Plato's Cratylus 410D) does not say more that just this. It seems unjustifiable to render the word as 'the year' as is done regularly nowadays, for the simple reason that there is no such thing as the year; to begin with, there is the tropical year and sidereal year, neither of them being of the same length as the Sothic year. Actually, the methods of Maya, Chinese, and Indian time reckoning should teach us to take much greater care of the words we use. The Indians, for instance, reckoned with five different sorts of 'year', among which one of 378 days, for which A. Weber did not have any explanation. That number of days, however, represents the synodical revolution of Saturn. Nothing is gained by the violence with which the Ancient Egyptian astronomical system is forced into the presupposed primitive frame. The eniautos of the Phoenix would be the said 500 (or 540) years; we do not know yet the stag's own timetable: his 'year' should be either 378 days or 30 years, but there are many more possible periods to be considered than we dream of - Timaios told us as much. For the time being the only important point is to become fully aware of the plurality of 'years', and to keep an eye open for more information about the particular 'year of the stag' (or the Oryx), as well as for other eniautio, especially those occurring in Greek myths which are, supposedly, so familiar to us, to mention only the assumed eight years of Apollo's indenture after having slain Python (Plutarch, De defectu oraculorum, ch. 21, 421C), or that 'one eternal year (aidion eniauton)', said to be '8 years (okto ete)', that Cadmus served Ares ..." A rat has no antlers and it cannot 'bring fire'. But the henna-stained fingertips of Cassiopeia should make us remember the finger nails of Mahuika (cfr in the chapter Tapamea) who produced fire: ... The Arabians called it Al Dhāt al Kursiyy, the Lady in the Chair - Chilmead's Dhath Alcursi, - the Greek proper name having no significance to them; but the early Arabs had a very different figure here, in no way connected with the Lady as generally is supposed, - their Kaff al Hadib, the large Hand [cfr Caph] Stained with Henna, the bright stars marking the fingertips; although in this they included the nebulous group in the left hand of Perseus. Chrysococca gave it thus in the Low Greek Χείρ βεβαμένη; and it sometimes was the Hand of, i.e. next to, the Pleiades, while Smyth said that in Arabia it even bore the title of that group, Al Thurayya, from its comparatively condensed figure ... ... 'What do you want here?' 'I am come to beg some fire of you. All the fires in our village have gone out.' 'Welcome! Welcome, then!' cried the old woman, 'Here is fire for you.' And she pulled out the nail of koiti, her little finger, and gave it to him. As she drew it out, fire flowed from it ... 5 (or V) implies 'fire', thus the finger-nails. Henna is used to colour hair, skin, etc., e.g.:

My imagination is running wild, you could say, but it would explain one of the items marked (?) at rima:

According to the Chinese it was the Rat who began the year (cfr at Kiore):

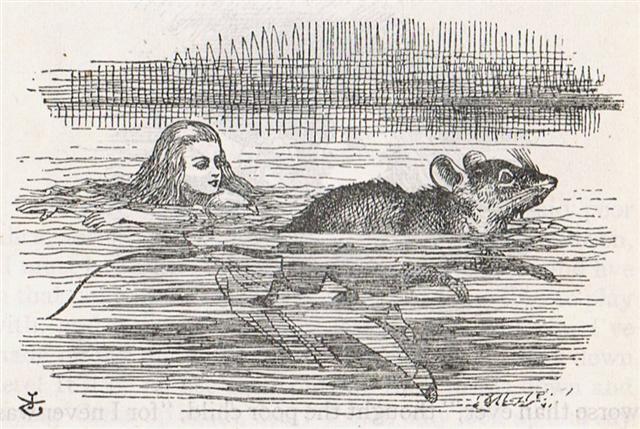

... This Chinese zodiac, however, progressed in reversed order from our own, opposed to the sun's annual course in the heavens, and began with the Rat. It was known as the Yellow Way, the date of formation being assigned to some time between the 27th and 7th centuries before our era, and the twelve symbols utilized to mark the twelve months of the year. It was borrowed, too, by neighboring nations ages ago, some of its features being still current among them. ... To follow the first part of the journey of the kuhane of Hau Maka is to move in reversed order compared with how Sun moves. The position of the Black Rat in the 'aquarium' proves he is the opposite of the Yellow Cat in Leo.

... None of the animals belong in the kingdom of fishes, which is an important fact ... As I understand it the reason must be that this is a zodiac (path for) Moon. She does not sail away far up in the sky like Sun in summer, neither does she dive down to the fishes in the Underworld in winter. She keeps to the Middle World ... Applying all these pieces of the puzzle we can guess Gb6-1 (the first glyph in the line which I from other considerations have found be a good candidate for the onset of the cycle - cfr at The Tail Feathers) depicts the Rat where the Yellow Way is beginning:

|