Possibly Metoro with his unusual comments early on side b tried to explain there had to be 3 nights added in order go from Hamal (*30) to Alcyone (*56). Because May 16 (136) - April 17 (107) = 29 (= 56 - 30 + 3):

Anyhow, his comments could have referred to the exceptional glyph Cb1-6:

... Rutua te pahu - the drums were sounding - i.e. when the sky was moving (rutua te maeva). Question is with how much the sky was moving. ... In China, every year about the beginning of April, certain officials called Sz'hüen used of old to go about the country armed with wooden clappers. Their business was to summon the people and command them to put out every fire. This was the beginning of the season called Han-shih-tsieh, or 'eating of cold food'. For three days all household fires remained extinct as a preparation for the solemn renewal of the fire, which took place on the fifth or sixth day after the winter solstice [Sic!] ... If 'the beginning of April' was the time for wooden clappers (probably equivalent to rutua te pahu), then the stars which once upon a time had told about the winter solstice must have moved ahead with around 365 + 91 (April 1) - 355 (December solstice) = 101 precessional days, an incredibly long stretch of time. Instead the explanation could rather be a change of the definition of where the year was beginning - for instance a change from winter solstice to the northern spring equinox ...

... The tun glyph was identified as a wooden drum by Brinton ... and Marshal H. Saville immediately accepted it ... [the figure above] shows the Aztec drum representation relied on by Brinton to demonstrate his point. It was not then known that an ancestral Mayan word for drum was *tun: Yucatec tunkul 'divine drum' (?); Quiche tun 'hollow log drum'; Chorti tun 'hollow log drum' ...

... The [tun] glyph is nearly the same as that for the month Pax ... except that the top part of the latter is split or divided by two curving lines. Brinton, without referring to the Pax glyph, identified the tun glyph as the drum called in Yucatec pax che (pax 'musical instrument'; che < *te 'wooden). Yucatec pax means 'broken, disappeared', and Quiche paxih means, among other things, 'split, divide, break, separate'. It would seem that the dividing lines on the Pax glyph may have been used as a semantic/phonetic determinative indicating that the drum should be read pax, not tun ... Thus, one may expect that this glyph was used elsewhere meaning 'to break' and possibly for 'medicine' (Yuc. pax, Tzel., Tzo. pox) ... It should be added that tun was also the period of 18 months, or 360 days:

And the Mayan Pax 20-day month was standing on 3 black balls:

... My arrangement has 15 Moan as the first month of 'winter', i.e. the time of the year corresponding to when sun has gone down in the west in the evening. The mouth which opened wide in spring (cfr 4 Zotz) to allow Sun to enter (in 5 Tzek) has closed again in 15 Moan to show that darkness has returned. The outside 3 black dots in 16 Pax are much greater than those in 9 Ch'en. Darkness falls first with the onset of the rain clouds (the grapelike hanging formation) and then when Sun leaves in autumn ... With each of these Mayan months carrying 20 days (excepting the last) there were 15 * 20 = 300 days before Pax. If my arrangement above should be changed - in order to follow the precessional movements of the star sky (ragi) - then Moan (the silent bird) would be in December and Pax in January, with Vayeb beginning with day 61 (March 2) and ending with March 6 (65). At the time of rongorongo precession had moved the Eye of the Bull to a place 65 days after 0h:

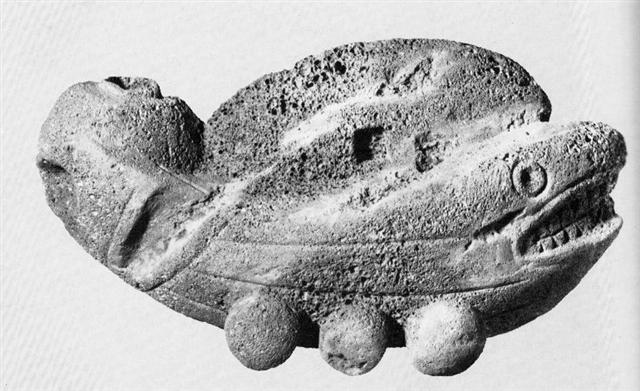

Could the 3 great black balls at bottom in the Pax glyph refer to how there was a break measuring 3 * 20 = 60 days from Moan to Pax? If so, then Vayeb would have ended with day 300 + 60 + 60 + 5 = 425 = 7 * 60 + 5. We can compare with the sign of 6 stone (tau ono, as in the Pleiades, Tau-ono) balls under this canoe of Tagaroa (?) found on Easter Island:

Beyond the canoe building place (kua to i te heke), where Acrux was at the Full Moon, there were 6 glyphs to the end of side b:

740 (number of glyphs in the C text) - 7 (number of glyphs from Cb14-13 to the end of side b) - 3 (= 29 - 26) = 730 = 2 * 5 * 73 = 2 * 360. ... There is a couple residing in one place named Kui and Fakataka. After the couple stay together for a while Fakataka is pregnant. So they go away because they wish to go to another place - they go. The canoe goes and goes, the wind roars, the sea churns, the canoe sinks. Kui expires while Fakataka swims. Fakataka swims and swims, reaching another land. She goes there and stays on the upraised reef in the freshwater pools on the reef, and there delivers her child, a boy child. She gives him the name Taetagaloa. When the baby is born a golden plover flies over and alights upon the reef. (Kua fanau lā te pepe kae lele mai te tuli oi tū mai i te papa). And so the woman thus names various parts of the child beginning with the name 'the plover' (tuli): neck (tuliulu), elbow (tulilima), knee (tulivae). They go inland at the land. The child nursed and tended grows up, is able to go and play. Each day he now goes off a bit further away, moving some distance away from the house, and then returns to their house. So it goes on and the child is fully grown and goes to play far away from the place where they live. He goes over to where some work is being done by a father and son. Likāvaka is the name of the father - a canoe-builder, while his son is Kiukava. Taetagaloa goes right over there and steps forward to the stern of the canoe saying - his words are these: 'The canoe is crooked.' (kalo ki ama). Instantly Likāvaka is enraged at the words of the child. Likāvaka says: 'Who the hell are you to come and tell me that the canoe is crooked?' Taetagaloa replies: 'Come and stand over here and see that the canoe is crooked.' Likāvaka goes over and stands right at the place Taetagaloa told him to at the stern of the canoe. Looking forward, Taetagaloa is right, the canoe is crooked. He slices through all the lashings of the canoe to straighten the timbers. He realigns the timbers. First he must again position the supports, then place the timbers correctly in them, but Kuikava the son of Likāvaka goes over and stands upon one support. His father Likāvaka rushes right over and strikes his son Kuikava with his adze. Thus Kuikava dies. Taetagaloa goes over at once and brings the son of Likāvaka, Kuikava, back to life. Then he again aligns the supports correctly and helps Likāvaka in building the canoe. Working working it is finished ...

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||