Each month could therefore be associated with some easily recognizable star, either such a star which was rising heliacally (together with the Sun at the horizon in the east) or such a star which could be observed close to the Full Moon. This fact made it possible to construct a calendar for the year. But it did not determine how many months there were in each season: From the natives of South Island [of New Zealand] White [John] heard a quaint myth which concerns the calendar and its bearing on the sweet potato crop. Whare-patari, who is credited with introducing the year of twelve months into New Zealand, had a staff with twelve notches on it. He went on a visit to some people called Rua-roa (Long pit) who were famous round about for their extensive knowledge. They inquired of Whare how many months the year had according to his reckoning. He showed them the staff with its twelve notches, one for each month. They replied: 'We are in error since we have but ten months. Are we wrong in lifting our crop of kumara (sweet potato) in the eighth month?' Whare-patari answered: 'You are wrong. Leave them until the tenth month. Know you not that there are two odd feathers in a bird's tail? Likewise there are two odd months in the year.' The grateful tribe of Rua-roa adopted Whare's advice and found the sweet potato crop greatly improved as the result ... The Maori further accounted for the twelve months by calling attention to the fact that there are twelve feathers in the tail of the huia bird and twelve in the choker or bunch of white feathers which adorns the neck of the parson bird. (Maud Worcester Makemson, The Morning Star Rises. An Account of Polynesian Astronomy.)

As to the number of months in a year there could also have been room for discussions. 12 * 29½ = 354 nights but the Sun year was around 365¼ days. Possibly the last pair of months ('feathers') could have amounted to 59 + (365 - 354) = 70 nights. 10 * 29½ + 70 = 295 + 70 = 365. The method of referring to long 'feathers' for explaining long periods of time was used also by the creator of the G text, e.g. in Ga2-23:

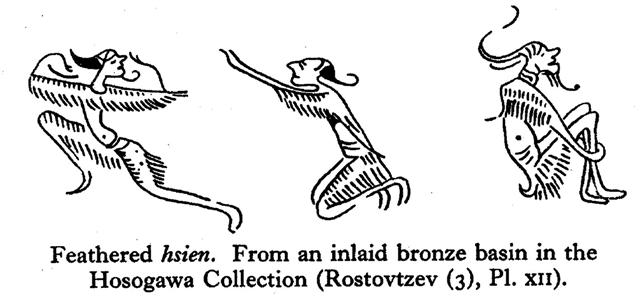

In many Polynesian cultures the bodies of gods were conceived of as covered with feathers and they were frequently associated with birds: in Tahiti and the Society Islands, bird calls on the marae signaled the presence of the gods. Hawaiian feathered god figures generally depict only the head and neck of the god. (Anne D'Alleva, Art of the Pacific.)

|