|

... Now every morning at

daybreak, Taranga used

to wake up before her

children and leave the

house, and vanish until

night. The older

brothers were used to

this, they knew that

their mother was there

at night but gone in the

morning, but little Maui

was not used to it and

he found it very

annoying. At first he

thought in the mornings,

'Well, perhaps she has

only gone to prepare

some food for us.' But

no, she really was gone,

she was far away.

In the evening, when her

children were all

singing and dancing in

the meeting house as

usual, she used to

return. And after the

dancing she called young

Maui to her sleeping

mat, and this happened

every night. And as soon

as the daylight came she

disappeared again.

One day Maui asked his

brothers to tell him

where their mother and

father lived. He said he

wanted to visit them.

They said they did not

know. 'How can we tell?'

they said. 'We don't

know whether they live

up there somewhere, or

down below, or over

there.' 'Well, never

mind,' said Maui, 'I'll

find them for myself.'

'Nonsense,' they said,

'how can you tell where

they are, you, the

youngest of all of us,

when we ourselves don't

know? After that first

night when you turned up

in the meeting house and

made yourself known to

us all, you know that

our mother slept here

every night, and as soon

as the sun rose she went

away, and she came back

at evening, and this is

how it always is. How

can we tell where she

goes?'

Now when Maui had this

conversation with his

brothers he had already

discovered something for

himself. During the

previous night, as his

mother and brothers were

all sleeping, he had

crept out and stolen his

mother's skirt, her

woven belt, and her

warm, feathered cloak,

and had hidden them.

Then he had taken

various garments and

stopped up all the

chinks around the

doorway of the house and

of its single wooden

window, so that the

first light of day would

not get in and Taranga

would not wake in time

to go. When that was

done he could not sleep.

He was afraid his mother

would wake up in the

dark and spoil the

trick. But Taranga did

sleep on.

When the first faint

light appeared at the

far end of the house,

Maui could see the legs

of all the other people

sleeping, and his mother

was sleeping too. Then

the sun came up, and

Taranga stirred, and

partly woke. 'What kind

of night is this,' she

wondered, 'that lasts so

long?' But because it

was dark in the house

she dozed off again. At

last she woke up

properly, and knew that

something was wrong. She

threw off the cloak that

covered her and jumped

up, with nothing on, and

went round looking for

her skirt and belt.

Little Maui pretended to

be fast asleep.

Taranga rushed to the

door, and the window

beside it, and pulled

out all the things that

Maui had used to stop

them up. When she saw

that the sun was already

in the sky she muttered

some angry things and

hurried out, holding in

front of her a piece of

old flax cloak that Maui

had used to stop up the

door. Away she ran,

crying and whimpering in

being so badly treated

by her children.

No sooner was she out of

the house than little

Maui was on his knees

behind the sliding door,

which she had closed

behind her as she left.

He was watching to see

which way she went. Not

far away he saw her stop

and pull up a clump of

rushes. There was a hole

under it, which she

dropped into. She pulled

the rushes into place

behind her, and was

gone. Maui slipped out

and ran as fast as he

was able to the clump of

rushes. He pulled it and

it came away, and he

felt a wind against his

face as he looked

through the hole.

Looking down, he saw

another world, with

trees and the ocean, and

fires burning, and men

and women walking about.

He put the rushes back,

and returned to the

house and woke his

brothers, who were still

fast asleep.

'Come on, come on! Wake

up!' he cried. 'Here we

are, tricked by our

mother again!' So they

all got up, and realized

from the height of the

sun that they had

overslept. That was the

day when Maui asked them

to tell him where his

parents lived. He did

not admit what he had

seen that morning. And

they said they did not

know, and he

would never know either.

'What does it matter to

you, anyway?' they said.

'Do we care about our

father or our mother?

Did she feed us and look

after us until we grew

up? Not a bit of it. She

went off every morning,

just like this. Our true

father, without any

doubt, is great Rangi

the Sky, whose offspring

provide us with trees

for our houses and birds

and fishes for us to

eat, and sweet potatoes

and fern root. And who

was it that sent those

other offspring down to

help us - Touarangi, the

rain that waters our

plants. Hau ma rotoroto,

the fine weather that

enables them to grow,

Hau whenua, the soft

winds that cool them,

and Hau ma ringiringi,

the mists that keep them

moist? Did not Rangi

give us all of these to

make our food grow, and

did not Papa make the

seeds sprout in the

earth? You know all

this.'

'I certaínly do know it

all,' said Maui. 'In

fact I know it far

better than you do. For

I was nursed and fed by

the sea-tangles, whereas

you four were nursed at

our mother's breast. It

could not have been

until after she weaned

you that you ate the

foods you speak of,

whereas I have never

tasted either her milk

or her cooking. Yet I

love her, because I once

lay in her womb. And

because I love her, I

want to find out where

she and our father live,

and go and see them.'

The other four were

astonished when they

heard their little

brother speak like this.

When they recovered

themselves and were able

to keep their faces

straight, they glanced

at one another and

decided that they might

as well let him have his

way, and go to find

their parents.

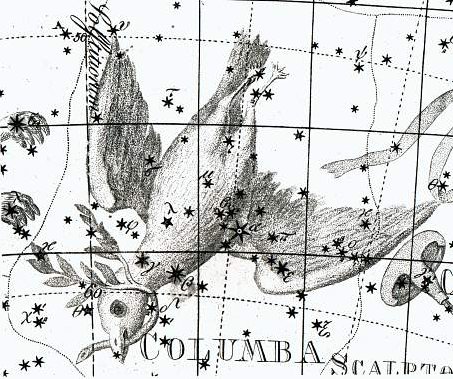

Now Maui had already

performed some of his

magic for them on the

night when they first

set eyes on him, in the

meeting house. On that

occasion, in front of

all his relatives, he

had transformed himself

into all kinds of birds

that live in the forest.

None of the shapes he

assumed had pleased them

particularly then, but

now he turned himself

into a kereru, or wood

pigeon, and with this

they were delighted.

'Heavens!' they said.

'You do look handsome.

Much more beautiful than

the birds you showed us

last time.' What made

him look so splendid now

was that he was wearing

the belt and skirt he

had stolen from his

mother that morning. The

thing that looked so

white across the

pigeon's breast was his

mother's belt. He also

had the sheen of her

skirt, that was made of

burnished hair from the

tail of a dog, and it

was the fastening of her

belt that made the

beautiful feathers at

his throat. This is how

the wood pigeon got its

handsome looks.

Maui now perched on the

branch of a tree near

his brothers, and there,

just like a real kereru,

he sat quite still in

one place. He did not

hop from bough to bough

like other birds, but

sat there cooing to

himself. Which made his

brothers coin our

proverb, 'The stupid

pigeon sits on one bough

and does not hop from

place to place.' And

they went away, and left

him to change his shape

again.

Next morning Maui

prepared to set off in

search of his parents.

Before he left, he

astonished his older

brothers once again by

making quite a speech.

'Now you stay here,'

said little Maui, 'and

you'll be hearing

something of me after I

am gone. It is because I

love my parents so much

that I am going off to

look for them. Listen to

me, and say whether the

things I have been doing

are remarkable or not.

Changing into birds can

only be done by someone

who is skilled in magic,

yet here I am, younger

than all of you, and I

have turned myself into

all the birds of the

forest, and now I am

going to take the risk

of growing old and

losing my powers because

of the great length of

the journey to the place

where I am going.'

'That might be so,' said

his brothers, 'if you

were going on some

warlike expedition. But

in fact you are only

going to look for those

parents whom we all

love, and if you ever

find them we shall all

be happy. Our present

sadness will be a thing

of the past, and we

shall spend our lives

between this place and

theirs, paying them

happy visits. What is

there to be afraid of?'

Little Maui went on,

very serious. 'It is

certainly a very good

cause that leads me to

undertake this journey,

and when I reach the

place I am going to, if

I find everything

agreeable, then I shall

be pleased with it, and

if I find it

disagreeable, then I

shall be disgusted with

it.'

The brothers kept

straight faces, and

replied: 'What you say

is exceedingly true,

Maui. Depart then, on

your yourney, with your

great knowledge and your

skill in magic.' Then

their brother went a

little way into the

forest, and came back in

the shape of a pigeon

once more, with his

sheeny back and his

white breast and his

bright red eye. His

brothers were charmed,

and there was nothing

they could do but admire

him, as he flew away.

Away flew Maui in his

pigeon shape, with his

brothers admiring him as

he went. But as soon as

he was out of sight he

wheeled about, and flew

to the clump of rushes

that marked the place

where his mother

disappeared.

He came down, in his

noisy pigeon way, and

strutted about for a

moment. Then he lifted

the rushes. He flopped

into the hole and

replaced the clump

behind him, and was

gone. A few strokes of

his wings took him to

that other country, and

soon he saw some people

talking to one another

on the grass beneath

some trees. They were

manapau trees, a kind

that grows in that land

and nowhere else.

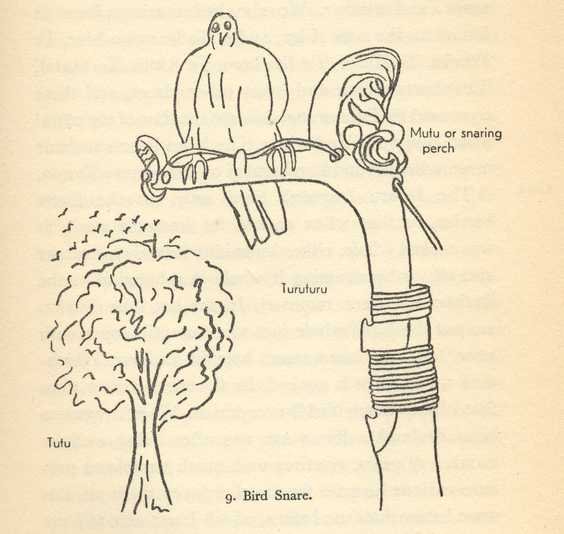

Maui flew down to the

tops of the trees and,

without being noticed by

any of the people,

perched on a branch that

enabled him to see them.

Almost at once he

recognized Taranga,

sitting on the grass

beside her husband, a

man who by his dress and

demeanor was plainly a

chief. 'Aha,' he cooed

to himself, 'there are

my father and my mother

just below me.' And soon

he knew that he was not

mistaken, for he heard

their names when other

members of the party

spoke to them. He

flopped down through the

leaves and perched on

the branch of a puriri

tree thad had some

berries on it. He turned

his head this way and

that, and tilted it on

its side. Then he pecked

off one of the berries

and gently dropped it,

and it hit his father's

forehead.

'Was that a bird, that

dropped that berry?' one

of the party asked. But

the father said No, it

was only a berry that

fell by chance.

So Maui picked some more

berries, and this time

he threw them down quite

hard, and they hit both

the father and the

mother and actually hurt

them a little. Then

everyone got up and

walked round peering

into the branches of the

tree. The pigeon cooed,

and everyone saw it.

Some went away and

gathered stones, and all

of them, chiefs and

common people alike,

began throwing stones up

into the branches. They

threw for a long time

without hitting the

pigeon once, but then a

stone that was thrown by

Maui's father struck

him. It was Maui, of

course, who decided that

it should, for unless he

had wished it, no stone

could have struck him.

It caught his left leg,

and down he fell,

fluttering through the

branches to the ground.

But when they ran to

pick the bird up, it had

turned into the shape of

a young man ...

(Maori Myths) |