4. Here I could have ended my 'preliminary remarks and imaginations'. Rona glyphs should, I have suggested, appear immediately 'inside' the beginning of a new season or cycle, and the twisted body posture ought to represent how 'movement' from now on goes in the other direction. This is enough to try out, for instance by looking at the beginning of texts after the tablets have been turned, e.g. represented by our wellknown pair Gb1-6--7:

I have not classified them as rona, but Gb1-13 (in position 242 + 1) is a rona glyph. However (a strange word which English Etymology does not care to explain), my ambition goes higher. In the preceding hupee chapter we have made a first (and fairly successful I would say) attempt at connecting the geography of Easter Island with the 'geography in the sky' and we ought to go on in that direction. Rona glyphs seem to be promising. In the following pages, not so few, I will try to arrange my ideas in as good an order as I can, but I know there is no King's way ahead. The terrain is difficult. So let's go: The entrance to a hare paega can be protected by 2 rona figures, or rather a Rona and a Runu I guess:

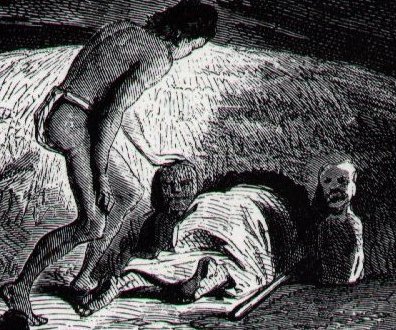

Not much is visible of them in this picture (cut out from a drawing by Pierre Loti - cfr at haú) but they are standing there and in between someone is crawling inside through the door opening. The door should be at a cardinal point, one of the corners of the 'square earth'. If so, then the location ought to be at equinox I imagine, because only the gods should enter a canoe at the stern or the prow (and a hare paega is the equivalent of an overturned canoe, the 'night side' of a canoe): ... to enter a war canoe from either the stern or the prow was equivalent to a 'change of state' or 'death'. Instead, the warrior had to cross the threshold of the side-strakes as a ritual entry into the body of his ancestor as represented by the canoe ... Métraux has mentioned these entrance figures: "The low entrances of houses were guarded by images of wood or of bark cloth, representing lizards or rarely crayfish. The bark cloth images were made over frames of reed, and were called manu-uru, a name given also to kites, masks, and masked people ..." The lizard (moko) and the crayfish (ura) form a pair of contrasts, one up on land and the other down in the sea. Manu-uru are not real 'birds', just imitations (reflections) made of 'straw'. Metoro said toa tauuru for 7 of the periods of the night (cfr Aa1-37--46). In my added item for uru in the Polynesian dictionary I have commented that uru usually means breadfruit (= 'skull') and that its fruit resembles a human skull. A cranium and uru symbolize, I think, the end of life - which has great nutritional value. Uru has 2 u, as is should for a 'back wheel'. Nightfall and morning connect the diurnal cycle with the yearly cycle. The hour of midnight was preferably a time for sleep, because at that time (equal to new year) there was a 'door' open through which figures of fancy and fear moved. Métraux has given us a good description of how it was to sleep in a hare paega: "... The most vivid description of hut interiors is given by Eyraud ... who slept in them several nights: Imagine a half open mussel, resting on the edge of its valves and you will have an idea of the form of that cabin. Some sticks covered with straw form its frame and roof. An oven-like opening allows its inhabitants to go inside as well as the visitors who have to creep not only on all fours but on their stomachs. This indicates the center of the building and lets enter enough light to see when you have been inside for a while. You have no idea how many Kanacs may find shelter under that thatch roof. It is rather hot inside, if you make abstraction of the little disagreements caused by the deficient cleanliness of the natives and the community of goods which inevitably introduces itself ... But by night time, when you do not find other refuge, you are forced to do as others do. Then everybody takes his place, the position being indicated to each by the nature of the spot. The door, being in the center, determines an axis which divides the hut into two equal parts. The heads, facing each other on each side of that axis, allow enough room between them to let pass those who enter or go out. So they lie breadthwise, as commodiously as possible, and try to sleep." Métraux has also given us a close-up picture of one of these manu-uru figures:

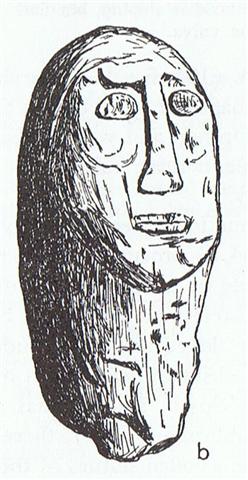

"The nose is narrow and straight and on the same plane as the forehead. The mouth is formed by two parallel raised strips. The oval eyes protrude. The cheekbones are two crescentic prominences ..." |