|

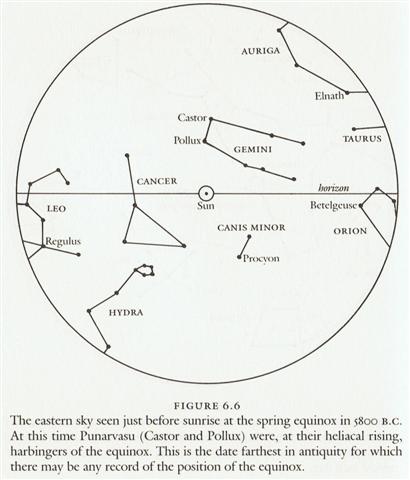

"In Hindu legend there was a mother goddess called Aditi, who had seven offspring. She is called 'Mother of the Gods'. Aditi, whose name means 'free, unbounded, infinity' was assigned in the ancient lists of constellations as the regent of the asterism Punarvasu. Punarvasu is dual in form and means 'The Doublegood Pair' ['Two Good Again' according to Allen]. The singular form of this noun is used to refer to the star Pollux. It is not difficult to surmise that the other member of the Doublegood Pair was Castor. Then the constellation Punarvasu is quite equivalent to our Gemini, the Twins. In far antiquity (5800 B.C.) the spring equinoctial point was predicted by the heliacal rising of the Twins (see fig. 6.6). By 4700 B.C. the equinox lay squarely in Gemini (fig. 6.7).

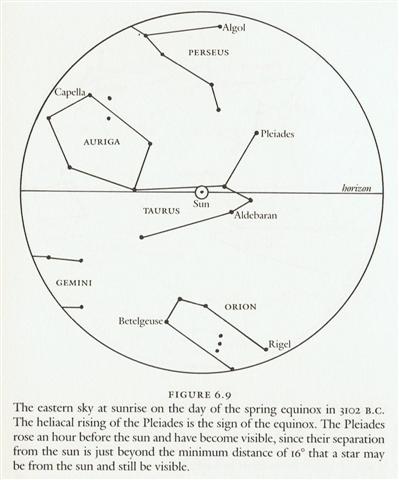

Punarvasu is one of the twenty-seven (or twenty-eight) zodiacal constellations in the Indian system of Nakshatras. In each of the Nakshatras there is a 'yoga', a key star that marks a station taken by the moon in its monthly (twenty-seven- or twenty-eight-day course) through the stars. (The sidereal period of the moon, twenty-seven days and a fraction [27.3] , should be distinguished from the synodic, or phase-shift period of 29.5 days, which is the ultimate antecedent of our month.) In ancient times the priest-astronomers (Brahmans) determined the recurrence of the solstices and equinoxes by the use of the gnomon. Later they developed the Nakshatra system of star reference to determine the recurrence of the seasons, much as the Greeks used the heliacal rising of some star for the same purpose. An example of the operation of the Nakshatra system in antiquity can be seen in figure 6.9

Here we see that the spring equinox occurred when the sun was at its closest approach to the star Aldebaran (called Rohini by the Hindus) in our constellation Taurus. But, of course, the phenomenon would not have been visible because the star is too close to the sun for observation. The astronomers would have known, however, that the equinoctial point was at Aldebaran by observing the full moon falling near the expected date or near a point in the sky exactly opposite Aldebaran (since the full moon is 180º from the sun), that is, near the star Antares; see fig. 6.15.

The system of Nakshatras, then, is quite distinct from systems that use the appearance of heliacally rising or setting stars as the equinoctial marker. Furthermore, the Indian system is all but unique in that two calendar systems competed with each other - a civil system, in which the year's beginning was at the winter solstice, and a sacrificial year, which begins at the spring equinox. The beginning of the former was determined by the Nakshatra method, observing the winter full moon's apparition near the point of the summer solstice in the sky (as explained above). The arrival of the beginning of the sacrificial year might be determined by the Nakshatra method - observation of the spring full moon near to the autumn Nakshatra in Virgo. More commonly, however, it was determined as in the Greek system, by direct observation of the heliacal rising of a sign star. In the current calendar, for example - one unchanged since the fifth century A.D. - the yoga star of the Nakshatra Ashvini (beta Arietis) ushers in the spring equinox at its heliacal rising." (Worthen) |