|

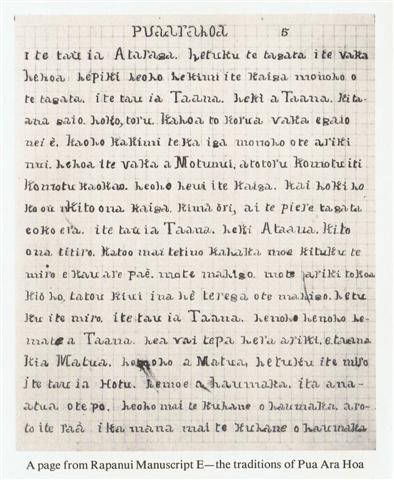

Sometimes I regret that I have no access to the original Manuscript E, and this is one of those times. The ortography of the manuscript is peculiar, for example in not using capital letters at the beginning of a sentence. Barthel has reproduced only page 5:

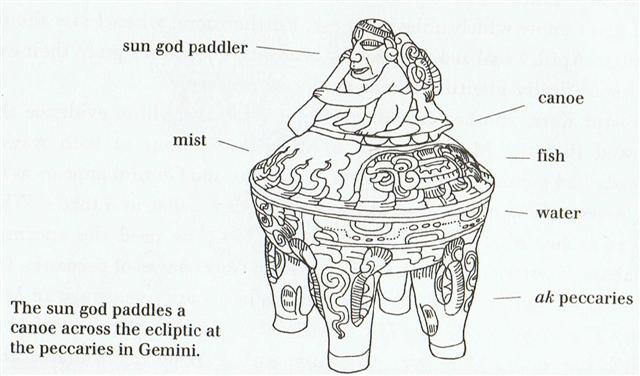

Sentences end with a full stop (.) and then there is a vacant space before next sentence, as we can see for instance in the 1st line: I te tau ia Ataranga. hetuku te tagata i te vaka A capital letter is here used not only for the important person Ataranga but also at the very beginning of the page. According to his 'improved' text (Barthel 2 pp. 305-306) this line becomes: I te tau i a Ataranga.he tuku te tagata i te vaka Breaking ia into two pieces seems to be a bit of pedantery which hardly is necessary, the meaning should be understood anyhow. The risk of destroying a pun or some other intended effect should not be underestimated. Even more so should he have avoided molesting hetuku into he tuku. I cannot see any translation of this part of Manuscript E in Barthel 2, but tuku can mean 'to slacken, let go' etc which is something quite different from hetu'u (star, planet) - as e.g. in Tehetu'upu (February). Ataranga belongs at the end of last year, I think, and so did February according to old custom. At new year a canoe (vaka) is launched, and inside should be at least the captain himself, possibly indicated only by tagata. He should be sitting with his soles flat on the deck (tukuturi), and he is the 'star' (hetu'u) - Sun - of the new year. Such are the imaginations emerging in my mind, and I remember from Maya Cosmos (cfr at hakaturou):

Tuku also means 'to go back to the boat' (and other interesting possibilities for word play). The truth is that we cannot rely on Barthel 2 as regards what Manuscript E really says. When reading sign language nothing must be changed, or the meaning will be destroyed. Already to alphabetize sign language is to decrease meaning. It must also be noted how Barthel quite unnecessary has eliminated space between full stop signs and the next word (at the beginning of next sentence):

This has been done with full consequence throughout his reproduction of the Rapanui text, giving an impression that the author of the Manuscript did not know the basic rules of writing. Darwinism has tampered with the mind of Barthel, I guess. The ancients (or those who belong to generations preceding us) were not stupid. On the contrary, they were sharper, more thoughtful people. As to the full stop signs, leaving no room prior to next word in the 'improved' version, there is a mystery. By contracting the text in the way Barthel has done at full stops the attention of the reader of course will be driven towards these curious full stops. My own reaction - before I had discovered that he had changed in the original text - was that these full stops must have some corresponding sign in the rongorongo texts, for instance in the form of 'lines of measurement':

I even tried to count the full stops to look for structure. And there is structure:

18 text lines in the 2nd list of place names have no full stop and these I have denoted with black zeroes, black because I guess they are 'indistinct' (in the 'mist') - like the 3 'overcrossed' items which I have denoted with black dash signs. The blue numbers in my table above indicate how many full stops there are in each of the text lines. For instance are there 16 full stops on page 38, distributed as follows:

16 + 14 = 30, and 7 + 9 (both odd numbers) = 16, which accumulates to 46. Together with the 2 full stops in the exceptional page 42 it becomes 48 = 2 * 24 = 4 * 12 = 6 * 8 = 3 * 16. But this my discovery of structure is not reliable because unfortunately I cannot rely on the text in Barthel 2. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||